Let's take a look into the significance of insights on Living Standard Measures (LSM), socio-economic dynamics within South African townships and the potential impact of shopping malls on townships.

Image supplied

South Africa has 532 African/Black, Asian/Indian and Coloured townships that have a geographic area greater than both Johannesburg and Durban combined. In 2019, there were 21,7 million people living in these townships. Gauteng with 8,9 million people has the largest township population followed by the Western Cape with 3,2 million people.

Living Standard Measures explained

The Living Standard Measures (LSM) is a powerful segmentation tool that categorises the consumer market into a continuum of ten groups based on household assets from LSM 1 to LSM 10.

The first five LSM groups are predominantly found within the rural areas of South Africa with LSM 1 and 2 being found in deep rural areas. These two LSM groups have over recent years largely disappeared but reappear as rural households become vulnerable to economic shocks and return to their poverty traps.

LSM 3-5 are found mainly within the rural towns and parts of the more impoverished metropolitan townships. When mapping the LSM it clearly shows that LSM 6 is what dominates within the African/Black townships in South Africa. LSM 7 and 8 have historically represented the Coloured and Asian/Indian townships or areas of the African townships where there are higher living standards.

LSM 9 has traditionally been found in the middle income White suburban areas while LSM 10 is the higher capital income communities in South Africa.

Although the LSM is considered outdated by many researchers, it still provides an invaluable understanding of how the socio-economic dynamics of communities are changing. Many compnies continue to use the LSM as a mechanism of describing their target market.

Other organisations believe that the Socio-economic Measure (SEM) is a more current and relevant way of describing communities especially in terms of the consumer behaviour and media consumption. Statistical correlation of the LSM and SEM shows that they largely map onto one another.

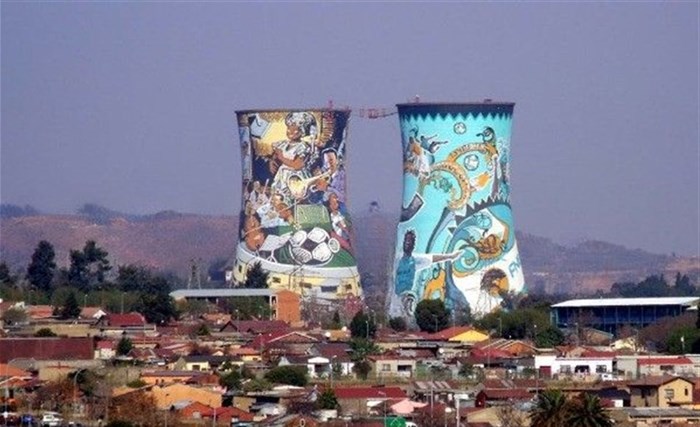

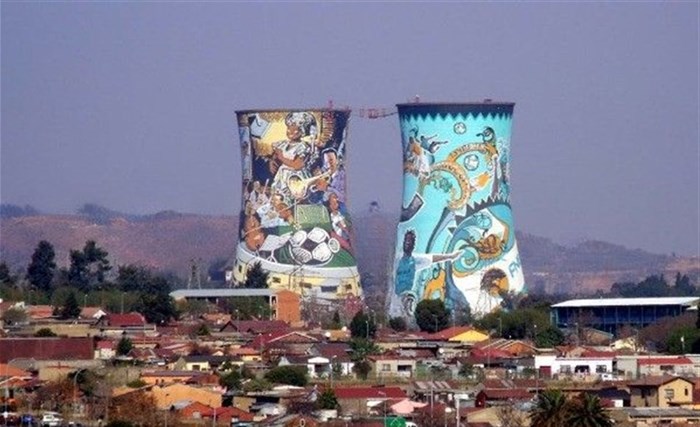

Soweto is one of the most recognised township in South Africa and boasts a population of over 1,7 million people, with an average household size of 4.8. This bustling township primarily reflects an LSM 6 living standard, but there are clear trends that areas within the townships are climbing up the LSM continuum.

An impressive 81% of Soweto's inhabitants indicate that they will continue to live in the township, citing various reasons for their attachment to this communities. However, other households with more disposable income and improvements in their living standards have migrated to nearby affluent suburbs.

For the private sector, this information is vital in making more informed decisions about the location of their outlets, targeting their customers with suitable products, and developing their marketing and media strategies.

For government, knowing the distribution of LSMs facilitates them implementing appropriate development strategies.

There is no doubt that as a household asset index, the LSM continues to provide an important view of the consumer market in South Africa and how it is changing, especially in the townships.

Shopping malls are catalysts for economic development

The development of shopping malls within townships has the potential to stimulate economic growth. This is based on the theory of “new economic geography” made popular by the economist Krugman that includes the principle of “circular causation”.

In layman terms, this principle states that when you have economies of scale or markets of a particular size with the cost of transport declining, businesses will concentrate at core locations.

The development of shopping centres in townships provides these economies of scale at core locations and through circular causation can bring about economic growth.

With this economic growth comes the opportunity for job creation and employment of local resident within the shopping mall as well as in secondary and tertiary industries.

By leveraging the integration of geospatial information, shopping centres can be developed in optimal locations in townships that can benefit their economic development and improve resident’s living standards.

To be able to develop appropriate interventions to improve the lives of people living in townships as well as to develop appropriate policies, requires access to granular geospatial data layers.

These data layers would include the boundaries of townships, and data on malls, retail outlets and government service points.

Current demographic data and information on housing, especially backyard dwellings are vitally important. Backyard dwellings play a critical role in the socio-economic character of townships but also have a significant impact on bulk services.

The value of this geospatial data

Economic data, especially income, is critically important to understand the potential of townships, the viability of communities and opportunities for businesses. To be able to communicate with township communities requires an understanding of all forms of media covering them.

Geospatial data of this nature is an asset especially when it can be used to implement appropriate strategies and policies.

The value of this geospatial data for townships is that it provides the necessary data to make informed decisions about the sustainable development of shopping malls. Lessons must be learnt from the developing shopping centres in the higher per capita income suburbs in the country where markets have been saturated by the development of too many shopping malls.

Although shopping centres have been built in many of the townships there is still opportunity for shopping malls in unserved townships and the ability to fill the gaps with smaller forms of shopping centres.

Charl Fouché,

AfriGIS 27 Nov 2023 What is vital in pinpointing the exact location of shopping centres in townships is the use of proper accessibility modelling methods. These methods take all the required information into consideration including the required capacity for a shopping mall to be financially viable and its proximity to the target market.

In more recent years, the necessity to take consumer purchasing behaviour into consideration has become vital in making decisions about the type of shopping centre that should be developed in townships. In the South African context, the best source of this information is the Marketing All Product Survey (MAPS) from the Market Research Foundation (MRF).

In conclusion, South African townships are vibrant hubs of cultural diversity and economic potential, embodying a complex interplay of historical legacies and evolving socio-economic landscapes.

Through an exploration of Living Standard Measures (LSM) and the impact of shopping malls, a nuanced understanding of the intricate relationship is established and the potential for economic development in townships. Leveraging these insights becomes crucial not only for businesses but also for policymakers.

The use of geospatial data must take centre stage in strategic decision-making, necessitating an understanding of where to locate shopping centres in relation to granular data on consumer behaviour in townships.