#PulpNonFiction: The principle of optimism

Optimism is, sadly, out of fashion. Everywhere I look, I see lonely optimists being insulted for their ‘stupidity’ in the face of what their critics believe is a hopeless situation; and even being accused of causing some sort of harm, by their rejection or questioning of the doomsday prophecies that are all so popular right now. Conversely, pessimism can be quite a profitable strategy for scientists, economists and politicians looking to build a name for themselves.

As the evolutionary scientists and author Matt Ridley says, “You don’t get blamed for being too pessimistic, but you do get attention. It’s like climate science. Modelled forecasts of a future that is scary is much more likely to get you on television.”

Even worse, pessimism can cause self-fulfilling prophecy feedback loops. After all, in life, as in business, it is very easy to prove predictions of failure correct; all you have to do is nothing, fail to even try and failure is assured, the pessimist is proved correct again.

Optimism, the pragmatic kind rather than the blindly naive kind anyway, is harder. Pragmatic optimism takes work and encourages action if one wants to increase the odds of success.

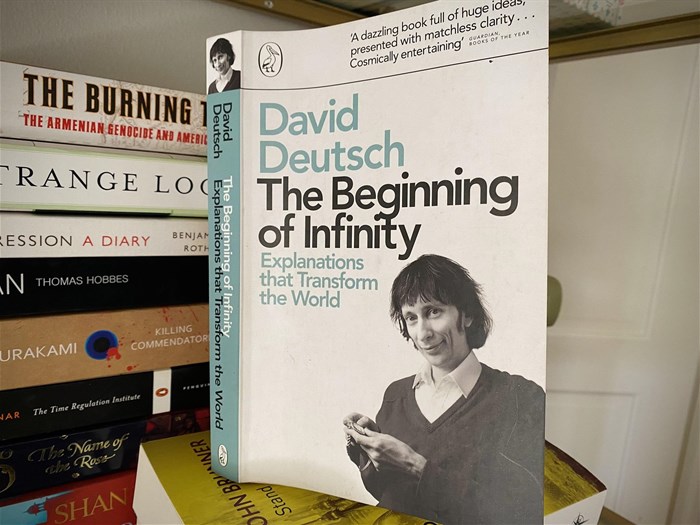

With this in mind, I have been reading David Deutsch’s The Beginning of Infinity. The book makes a strong case for, as it calls it, the principle of optimism.

He distinguishes his principle of optimism from blind optimism, which he defines as “proceeding as is we know bad outcomes will not happen” and from blind pessimism, adherence to the precautionary principle, which he describes as “avoiding everything not known to be safe”. Rather, he defines his principle of optimism as understanding that “all evils are caused by insufficient knowledge.”

This represents a rare positive attitude to scientific advancement (also not a very popular position these days, when public and media sentiment is turning against tech companies, engineering and industry, bio-science advancements, and the scientific community at large).

As he explains, when we try and predict the likelihood of future disasters based on our current level of knowledge and technological capability (much like old Malthus did with his gloomy predictions of mass starvation and societal collapse arsing from human population growth out stripping food production growth) we are bound to be overly pessimistic about the future. Of course we can’t solve tomorrow’s problems with today’s tools; but we have a very good chance of solving tomorrow’s problems with tomorrow’s scientific breakthroughs, ideas and opportunities that we cannot even imagine right now — as long as we keep on learning and trying and testing.

Of course, the exact same principle of optimism applies to business. We don’t even know what we will be capable of tomorrow.