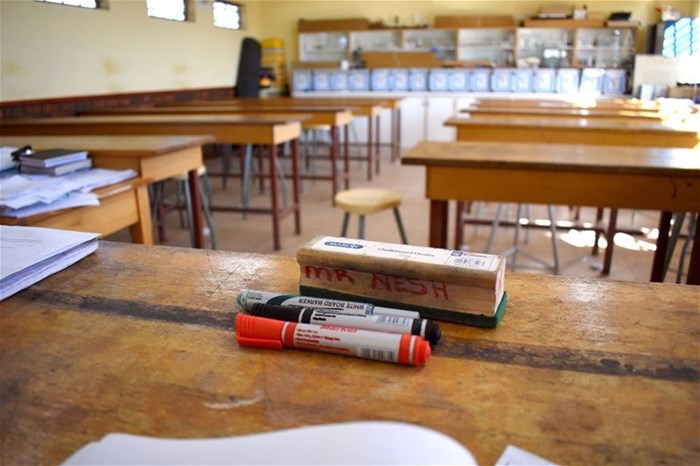

The release of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) has sounded alarms regarding the state of learning in South Africa.

Image supplied

The study found that 81% of Grade 4 learners in South Africa cannot read for meaning in any language. In 2016, PIRLS revealed that it was 78% of Grade 4 children. This is a three percentage point increase since the 2016 study and confirms the concerns numerous stakeholders in the education sector have raised.

South Africa’s Grade 4 learners scored an average of 288 points in the study, which is significantly lower than the 500-point international mean, and a 32-point decrease from the 2016 results. It is worth noting that 21 of the countries that participated in the study also experienced a decline in result, which has predominantly been attributed to the pandemic. South Africa’s decline however is one that unfortunately indicate a regression to levels last seen a decade ago.

“The results have confirmed a worrying downward trend in the foundational learning of our children. This decline is cause for further concern regarding the pandemic’s impact on our learners and requires drastic action,” said Zero Dropout programme director, Merle Mansfield.

A recent report by University of Cape Town Professor, Ursula Hoadley, tracked curriculum and assessment policy changes within South Africa since the pandemic and alarmingly found that: “There has been no attempt to recoup time in order to remediate learning losses, apart from very recent attempts in one province.”

“Without concerted efforts to re-engage learners and implement accelerated catch-up programmes the knock-on effects of the pandemic’s school closures and rotational timetabling will continue to be felt down the line, especially for learners in Quintile 1-3 schools, which bore the brunt of these policies,” added Mansfield.

Accelerated learning programmes

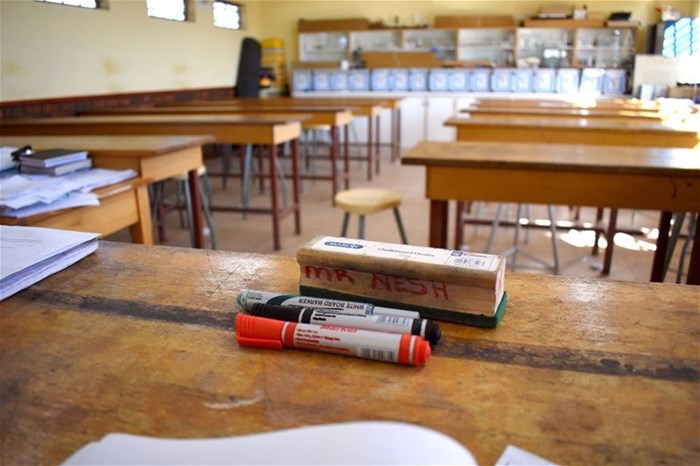

For the past three years, the Zero Dropout Campaign has been advocating for accelerated learning programmes (ALPs) and early warning tools to mitigate the learning loses caused by COVID-19 school closures and rotational timetables.

“Reading comprehension is a significant contributor to learners falling behind academically and repeating grades. In 2021, it was found that by the end of primary school, 36% of learners were already overaged and by Grade 12, that proportion rose to 56%,” added Mansfield.

ALPs have been widely recognised as ‘best practice’ for countries such as South Africa currently experiencing high learner repetition rates and foundational learning crises. The pandemic has exacerbated the need for ALPs across the country and available evidence suggests that some learners in South Africa lost as much as an entire school year since the first lockdowns. These losses, particularly those experienced by foundational phase learners, will likely undermine the development of an entire generation for years to come.

Corrin Varady 25 Apr 2023 The Zero Dropout Campaign has over the past years initiated ALPs across the country such as Reading for Meaning programmes in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal, and most recently Northern Cape, Free State. Through principles such as Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL), Reading for Meaning focusses on a child’s learning needs rather than their age or grade to support pupils who missed key literacy and numeracy concepts early in life.

In a post-pandemic learning environment, ALPs are critical and should be prioritised as learners who have fallen behind academically and repeated years are at much greater risk of not returning to school, which in turn places their prospects of securing a qualification and employment opportunities in future at serious risk.

Language

PIRLS 2021 were conducted in all official South African languages at the time to accommodate as many learners as possible and give them the best chance at comprehension. However, it is reported that somehow only 66% of learners were tested in their home language.

This was also the first year where Grade 6 learners in South Africa were assessed and they scored 384 points, a significantly higher score than their Grade 4 counterparts. The Department of Basic Education in part attributed this improvement in results to children learning in their mother tongue from a foundational phase and being assessed in the same language, particularly English and Afrikaans in this instance. Three quarters of Grade 6 learners, however, were not tested in their mother tongue, so more improvement can be expected in future if this language gap is bridged.

“Learning in the ‘right’ language or ‘mother-tongue instruction’ is also a crucial component for learners’ engagement, development, and subsequent assessment, and more should be done to make it more accessible,” concluded Mansfield.