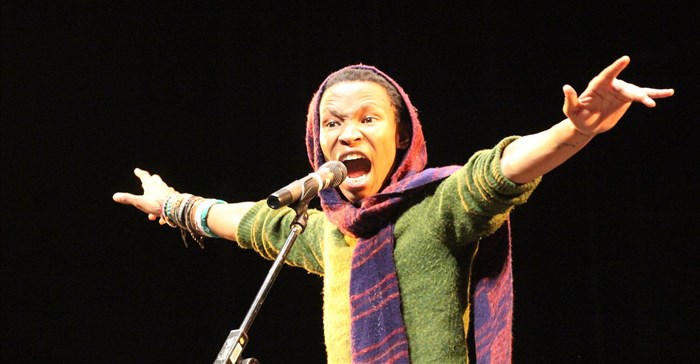

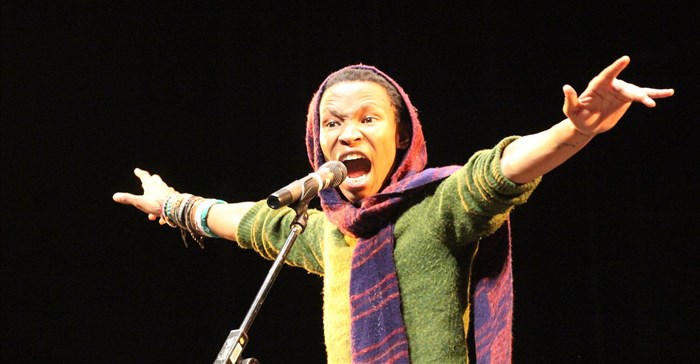

South African writer, performer and new media artist, Xabiso Vili, was recently announced as one of six finalists in the Future Africa: Telling Stories, Building Worlds programme.

Image supplied: Xabiso Vili

The programme focused on investing in the next generation of Extended Reality (XR) creators in Africa and was hosted by Africa No Filter in partnership with Meta.

Vili’s visual XR album, Black Boi meets Boogeyman is a speculative fiction piece that explores turning toxic masculinity into compassionate masculinity. "We are truly excited and honoured to get the opportunity to bring this project to life. We have a steadfast belief that stories will heal the world, and to be at the forefront of a grant of this scale reminds us that we have begun the healing," he said.

We spoke with Vili to find out more about XR, his work and masculinity in the African context…

Tell us a bit more about yourself - who is the person behind the art?

I am a writer, performer, new media artist and a believer in "what if?" I believe the stories we tell are spells we weave into the very fabric of reality to make the world we see around us, including ourselves.

As such, I am always excited to explore new innovative forms of storytelling. What is the new figurative fire we all sit around to commune with and in each other? I was an awkward child growing up and it was through poetry and writing that I could find my voice to be able to better relate to my peers - I am very cognisant of the many ways art has saved my life - and to that end, I am constantly working towards helping others access a similar experience.

I am currently doing my postgrad in applied theatre and drama therapy and this process is deepening my toolset in how I can use art to heal individuals, communities and all different kinds of societies and cultures. So, the person behind the art is an individual with complex motives and driving forces that wonders about all the many possibilities of changing the world around us.

How are you feeling about your selection for the Future Africa Grant?

I am truly flabbergasted, excited, in disbelief, and determined - I am sitting in a crucible of emotions. I always reference a quote by Steve Biko when he says, “The great powers of the world may have done wonders in giving the world an industrial and military look but the great gift still has to come from Africa – giving the world a more human face”. I think this is the thing that fuels me most when it comes to this Future Africa Grant - this is a pivotal moment in XR history when African creators can pick up the mantle and be at the forefront of determining our own stories and getting closer to that human face that the world so requires.

Could you tell us a bit more about Extended Reality content creation?

Extended Reality is an umbrella term for real-and-virtual environments. It encompasses AR, VR and mixed reality. But for content creation, it becomes a really powerful vehicle for blurring worlds and building empathy. It can take what is in our imaginations and put it right in front of us. Of course, other artforms do something similar - but I don't think I have ever encountered something as immersive as XR.

AR shifts and changes what is real around you through a lens or screen. You can think of Instagram filters for example - they distort your face through the screen or my project Re/Member Your Descendants which exhibited illustrations of people as ancestors and when you viewed the image through the phone, it would start moving and a poem would start playing.

VR, on the other hand, is a simulated experience which can be similar to or completely different from the real world. This is similar to Black Boi meets Boogeyman which we are creating through the Future Africa Grant, in this one, you don a headset and you are transported to a completely different world.

Mixed reality is a mixture of real and virtual worlds and can be present in a multitude of mediums from holograms to projection mapping. I exhibited a projection mapping installation in Paris that looked at the different faces and identities of Africa across the past, present and future - this used poetry and 3D animation to bring a church to life as images grew and moved around the facade of the Saint-Eustache. Those are some examples of how one could use XR for content creation.

How did you find yourself in this kind of content creation?

It was a gradual process. I think my base has always been poetry and storytelling. But I was always interested in how to collaborate and extend the different types of stories I would tell. As a result, I found myself experimenting with music, theatre, film, videos and many other mediums.

So, when I saw a call out to participate in a hackathon at the National Arts Festival with illustrators to create AR work, it was a no brainer for me. That was four years ago. From that moment, something shifted for me. A few months later, I received funding to create my first AR exhibition which has travelled from Paris to Vancouver and back to Johannesburg. That same exhibition opened doors for me to be able to create my first projection mapping installation as well.

Your new album looks at turning toxic masculinity into compassionate masculinity - what does this mean, and why is it important to you?

Compassionate masculinity is a term my friend and I came up with when we were discussing the alternatives to toxic masculinity during the lockdown. Toxic masculinity refers to certain norms and representations of masculinity that are harmful to society and ourselves. In devising compassionate masculinity, we were of the understanding that not all representations of masculinity are harmful or dangerous, rather, there must be work that men can do to reframe their relationships to masculinity in such a way that would be healing for them and thus society.

This is vital work for me especially since I am working in the space of healing. But more so, as a black man in South Africa - I am constantly aware of being a danger and being in danger at the same time. South Africa has some of the highest GBV rates in the world as well as some of the highest male suicide rates in the world. There's a violence that men in South Africa have been raised with and I think it is well overdue that we interrogate it and start to reimagine what a new form of masculinity might look like.

Does African masculinity differ in any way? If so, what kind of struggles would African men experience that are unique?

Let me first say that there are many forms of masculinity we share across the world and there are many that might mirror or allude to and resonate with other men globally. But I also think that there are forms of masculinity that we assume in Africa, in South Africa and then even locally in different provinces, regions, cities and towns.

We all have our networks of masculinities. In the Xhosa culture for example, when boys go up to the mountain to become men - many women complain about how those same men behave when they return. As though they are better than everybody now, how they show disrespect and assume ownership of everything around them.

Though that is not what they were taught on the mountain. Or how power structures show up in the traditional rituals we partake in, or how I am sure many men are familiar with the culture of the street corner, but I also believe that the toxic masculinity ecosystem shows up differently on different corners with varying degrees of similarities. These are just a handful of the scenarios Black Boi meets Boogeyman hopes to interrogate.

What advice would you give to people trying to join the conversation around masculinity?

I would say come with an open heart and a willingness to learn and unlearn. The process is simple, and it is by no means pain-free. But if we truly want change, we need to begin to interrogate ourselves and our roles in oppressing others - then interrogate and examine our societies and communities.

The work requires compassion and empathy, but also requires a firm hand and a bit of discipline. There is already a wealth of knowledge that exists, and one should always take it upon themselves to research anything that they might not understand. But, most importantly, you must find a support structure that holds and supports your growth and your breaking, because you will break. As Adrienne Rich says, "There must be those among whom we can sit down and weep and still be counted as warriors." And the weeping is the most important advice of all.