Top of mind for most South African citizens and businesses of late is the ongoing electricity crisis - in particular, how long before we see an end to load shedding. Without significant intervention, however, things are likely to get worse.

Source: Siphiwe Sibeko/Reuters

This is according to the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research's (CSIR's) Warrick Pierce, who is the principle researcher at its Energy Centre. Pierce unpacked the data behind how we got to this crisis point and where we currently stand.

What's driving the electricity crisis?

Load shedding, he said, is used as a proxy to demonstrate the extent of the crisis, but it's just a symptom of the problem and not the source. "The actual problem is that supply is not able to meet demand or, more recently, reliably meet demand," he explained.

What began a few years ago as a generation capacity shortage has now developed into a capacity and an energy shortage. "It's not just about our megawatts, it's also our megawatt-hours," he said.

The crisis is being perpetuated, he explained, by what in systems thinking is called a 'reinforcing loop' - Eskom sweats its existing capacity to keep the lights on, which leads to inadequate maintenance, followed by breakdowns and reduced availability and capacity. And so the loop, which ultimately triggers load shedding, continues, Pierce explained.

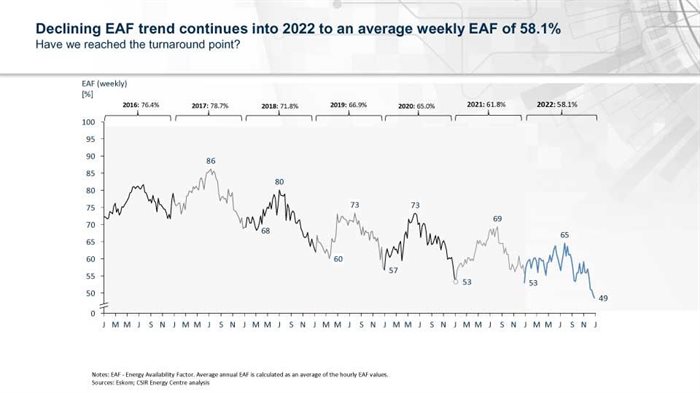

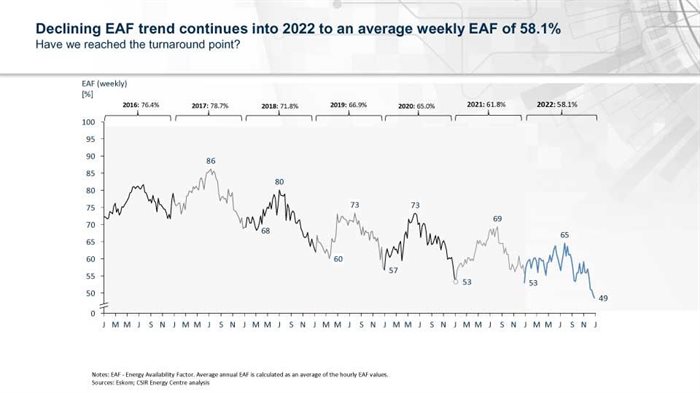

Eskom steadily built new coal power stations from the 1960s up until the 1990s, but this was followed by a dearth of new builds coming online during the 2000s, he highlighted. And while the current Eskom fleet, functioning at an energy availability factor (EAF) of 80-90% would meet the required national peak demand of 35GW, the problem is that its reliability is significantly reduced.

Source: Council for Scientific and Industrial Research

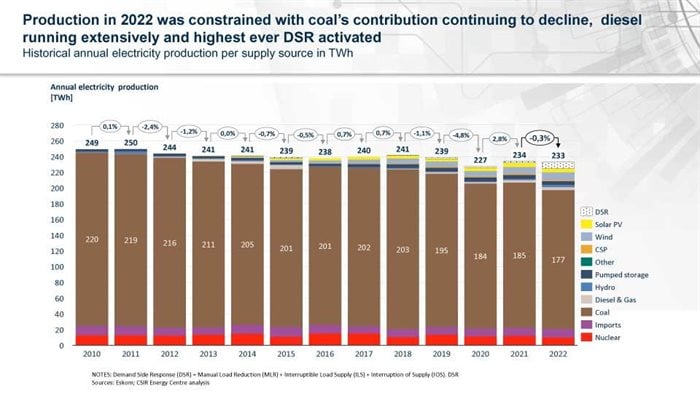

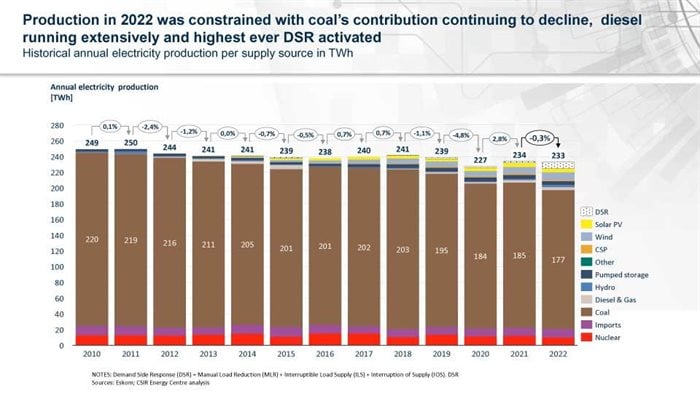

click to enlargeHe noted that electricity production from coal sources has steadily been reducing since 2010 when it generated 220TWh. In 2022, production from coal was at 177TWh - a big step change from 2021 when it was at 185TWh. That gap being left by coal is being filled by demand-side response, otherwise known as load shedding, explained Pierce, warning that if everything stays exactly the same, the electricity crisis will get significantly worse in 5-10 years' time.

How did we get here?

We have the megawatts, so why aren't we able to generate enough electricity to meet demand? The answer, explained Pierce, lies in the EAF which has been declining since 2017, reaching new lows in December 2022 when it dropped below 50%.

"We're sweating assets, we've got inadequate or not enough maintenance, increased breakdowns, and we've got ageing power stations, so we're seeing this increase in unplanned maintenance or breakdowns which is then reducing the availability that is worsening the crisis."

Source: Council for Scientific and Industrial Research

click to enlargePierce's data shows an almost exponential growth in load shedding since 2018 and a significant step-change from 2021 to 2022 with more than four-and-a-half times the amount of load shedding experienced last year compared to 2021. Of concern, he says, is that the most prevalent stage of load shedding was Stage 4 in 2022 versus Stage 2 in the previous year.

For now, there is no end to load shedding in sight, but key metrics to keep an eye on include an increase in generation capacity connected to the grid and the EAF which is currently on a declining trend.

"Once we can see that the EAF is stabilised and starts to improve, that will be a good sign for things improving and load shedding potentially coming to an end," said Pierce.