Top stories

More news

Marketing & Media

Ads are coming to AI. Does that really have to be such a bad thing?

However, the very fact that you’re able to read this piece wherever and whenever you choose makes it near impossible to quantify the impact that having no internet access has on someone. The good news is that the internet’s reach is being extended every day, thanks to a number of initiatives by stakeholders in both private and public sectors the world over.

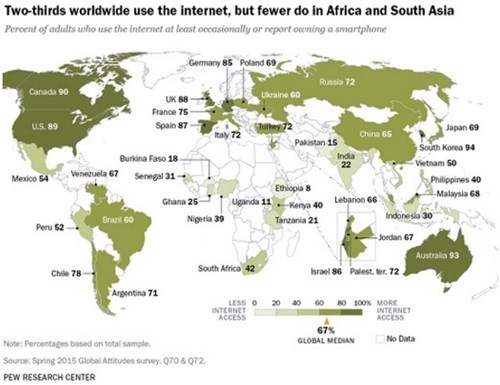

In fact, a recent Pew Research Center study on smartphone ownership and internet usage in emerging markets reveals that in 2015, a median of 54% among 21 emerging and developing countries reported using the internet at least occasionally. Unfortunately, even when compared to emerging market counterparts like Brazil, China and Russia, South Africa is doing rather poorly – with less than half of South Africans having reliable access to the internet.

The exorbitant costs associated with developing a fixed line infrastructure sufficient enough to meet the demands of the populace was met with a massive influx of wireless technology. Mobile data usage has grown at an extraordinary rate as a result, but its costs are still prohibitive to many whom spend a majority of their income on food, household goods and transport. The solution for many internet provision organisations is Wi-Fi, a fast and affordable alternative to mobile internet.

As a key player in the Wi-Fi provision game, I’m regularly asked, “Why can we not have free Wi-Fi like they do in London?” My explanation is a simple one: “Economy, location and geography.” It’s important to understand that the UK has a population of 64 million and a GDP of $2.8 trillion (R35.9 trillion), meaning a GDP per capita of $41k (R640K). By contrast, South Africa has a population of 56 million and a GDP of $0.8 trillion (R12.5 trillion), giving us a GDP per capita of $13k (R203K). That means that if we were to compare apples to apples, the UK is four times as likely to be able to fund, or at the very least subsidise, internet-based services.

Geographically, we also have a number of obstacles stacked against us. Our population is spread over 1,242 square kilometres and the UK’s is over 242 square kilometres. And guess what, they are more urbanised than us, with 33% of their population in the top 10 cities. We have around 13% of our population residing in our top 10 cities. Then consider that the UK, although this works for much of the developed world, is nestled between other developed economies – the US and Eurasia in the UK’s case. We found ourselves at the very tip of Africa. That means, to connect to the world, South Africa’s infrastructure has to span some 12,000 km.

It’s our geographical misalignment with the rest of the developed world that translates into increased costs, for the provider as well as the customer. No matter who you are, provision of internet services will always cost more in South Africa. Take the mobile network operators (MNO), at a purchasing price parity perspective, the three items above mean that they will always be more expensive than their developed economy counterparts. I do have a problem with the considerably larger profit margins of local mobile network operators, as compared to MNOs in comparative developed markets. On one hand, it’s great for them that they’ve been able to leverage more profit from the services they deliver. On the other, I can only imagine what opportunities cheaper MNO services would facilitate for South Africa.

Don’t get me wrong, philanthropy is not the solution. Without profitability, scalability goes out of the window. A ROI, therefore, is crucial to the development of internet provision, but the value earned needs to be only slightly higher than the cost invested if we’re to truly see internet access for all. The key is keeping it affordable, which is where Wi-Fi really shines.

At the end of the day, if you want free Wi-Fi, you’re going to get what you pay for. Data is still a very real cost, even in the UK, but they can afford to give it away for free due to having more cash on hand and cheaper input costs. Wi-Fi cannot be free in emerging economies because it will very quickly put those providers in the red. There is of course business in the provision of Wi-Fi, but the value proposition for the consumer will be Wi-Fi at volume, as it will be the primary connectivity for a vast part of the population. For the higher LSM market the value proposition would be the ease of use and quality of a paid for service versus a free service.

In the first world, the advent of Wi-Fi came about when there was already a significant backhaul and infrastructure established, with significant fixed line internet access as a result. Wi-Fi was seen as an additive service, an indulgence. In emerging markets, it will serve as the only point of access for many. The value proposition is a reliable and convenient service for the paying consumer at affordable rates, many of whom would otherwise have no access at all.

IT News Africa, established in 2008, is a leading provider of Africa focused ICT news and information aimed at technology professionals and businessmen.

Go to: http://www.itnewsafrica.com