Mesmerising Big Eyes

In the late-1950s and early 1960s, painter Walter Keane had reached success beyond belief, revolutionising the commercialisation of popular art with his enigmatic paintings of waifs with big eyes. The bizarre and shocking truth would eventually be discovered, though: Walter's works were actually not created by him at all, but by his wife Margaret. The Keanes, it seemed, had been living a colossal lie that had fooled the entire world.

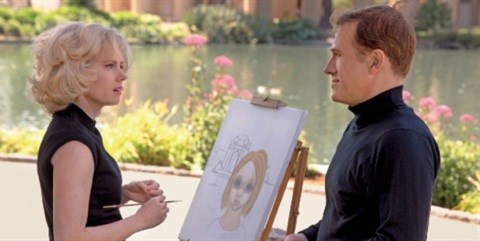

A tale too incredible to be fiction, Big Eyes centres on Margaret's awakening as an artist, the phenomenal success of her paintings and her tumultuous relationship with her husband, who was catapulted to international fame while taking credit for her work.

It is directed by Tim Burton (Ed Wood) and written by Golden Globe winners Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski (The People vs Larry Flynt and Ed Wood).

Stranger-than-fiction story

In 2003, writing partners Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski learned the stranger-than-fiction story of Margaret and Walter Keane, the top-selling painters of the 1960s. Intrigued, they began to research a story that would take 10 years to finally go into production.

"It's a great piece of history that nobody knows," says Alexander. "If it weren't true, I wouldn't believe it."

"There were a lot of reasons why we wanted to make this movie," says Karaszewski. "We thought Margaret was a great female character who embodied the beginning of the women's movement. It starts with her as a 1950s' housewife who does everything for her husband. Through the course of the story, she learns to stand up for herself."

Alexander and Karaszewski have a tremendous track record with biopics, having written films about comedian Andy Kaufman (Man on the Moon) and publisher Larry Flynt (The People vs Larry Flynt) and producing one about actor Bob Crane (Auto Focus).

"Scott and I are very attracted to these sorts of biographies of people who you initially didn't think were important and who were marginalised."

He notes that Ed Wood, their first film with Tim Burton, "was about someone who people thought was the worst filmmaker of all time. And there are some people who think the Keanes are the worst painters of all time. We thought by making this film we could tell a very great personal story, as well as discuss issues of the art world and the women's movement."

Revolutionised the art world

The writers were spellbound by the Keane's story. "Walter really invented the mass marketing of art," says Karaszewski. "He wasn't accepted in galleries and by art critics so he built his own galleries, put out his own coffee-table books. He figured out how to make the paintings so cheap that the average man could buy them and he totally revolutionised the art world. Certainly, people who came along later, like Peter Max or Thomas Kinkade, borrowed from his playbook, and even Andy Warhol acknowledges stealing a little bit from Walter Keane's philosophy. But what's amazing is the secret behind it all: the paintings were his wife's and he manipulated her into letting him put his name on them and taking all the credit. We were totally fascinated and thought this was a great American story that hadn't been told."

The writers spent weeks at libraries and poring through San Francisco newspaper stories in microfilm archives, trying to piece together the sensational tale of the Keanes. "It was hard to get a straight story," says Alexander, and they set out to meet with Margaret. "We needed to be able to earn her trust and show that we had integrity."

Keane agreed to a meeting and the writers flew up to her in San Francisco. "We had a really nice lunch," says Alexander. "We asked the questions that the newspaper stories didn't answer, which were: How did this happen? When was the first time Walter said he was the painter? What did he tell you? Why did you agree? And, as this went on for year after year after year, why did you continue to let him do this? Psychologically it didn't make a lot of sense. We started to understand though that she came out of a 1950s' housewife mentality in which the man was in charge of the household and laid down the rules and, in fairness to Walter, he promised a lot of things that came true. He said they'd become famous, make a lot of money and live in a big house. Years later, Margaret still says that without Walter nobody ever would have discovered her art. She still gives him a lot of credit."

Margaret Keane agreed to sell Alexander and Karaszewski the rights to her life as well as her art. "It took us one more year to work it out so Margaret would be comfortable," Alexander says. "We didn't want to do anything that was going to make her feel bad about the film. We had to earn her trust at all times."

Made it come alive

Today, Margaret is 86 years old and lives an hour out of San Francisco. Walter died in 2000, several years before the screenplay began to take shape. Margaret says: "Scott and Larry were so enthusiastic and they really wanted to do it the same way that I did, so I really felt secure with them. I had already got four other offers and turned them down, which is very difficult to do, but I couldn't trust what they would do so I said no."

"They made it come alive," Margaret says of Alexander and Karaszewski's script. "They found humour and tragedy in it. It's just marvellous. I feel like I'm being showered with blessings, having a movie. It's such an honour, and really sort of a humbling thing because I don't think I deserve this. I just paint and all of a sudden this is happening. It's like a dream. It's surreal."

Margret and Tim Burton knew one another before a screenplay was even in the works. "Tim commissioned me to do portraits and then he bought several of my paintings. I couldn't help but like him. I can't imagine anyone better than Tim Burton directing this film."

Keane makes a cameo appearance in the film in a scene filmed in San Francisco at the Palace of the Arts. "I was supposed to be a little old lady sitting on a bench, enjoying the day. It was so touching. Tim came over and handed me a little Bible and I thought to myself: 'How kind he is - he knows how much I like the Bible so he gave me one to read while I was sitting there.' It was a day I will always remember."

While developing Big Eyes, the plan had been that Alexander and Karaszewski would also direct. In 2007, with a draft in hand, they set out to make the movie. "It seemed to have a black cloud floating over it," says Alexander. "It almost got made several times, and it kept falling apart," says Karaszewski. "But the smartest thing that Scott and I ever did was never sell it. In all those various versions, we maintained control. And it finally worked out."

Alexander considers Walter Keane a genius. "He was the guy who said: Why can't you sell art in a supermarket, or a hardware store or a gas station? The art was mysterious to people and a big part of the mystery was that Walter was being presented as the painter. Here was a masculine guy painting crying children, and a great cockamamie story about the orphans after World War II, the skinny fingers and big eyes and sad faces, but something seemed off. Once you know the real story, which is that Margaret was sad and she was painting sad children, suddenly, it legitimises the art. The art became so popular there was a whole movement of rip-off art. If you were a kid in the 60s, you would see this art everywhere. He recalls his own introduction to the art as "those kind of spooky paintings I'd see at my aunt's house".

Not accepted by the conventional art world

While Keane was the top-selling artist, his work was not accepted by the conventional art world and considered kitsch. The literal, sentimental portraits of stylised children were a far cry from the abstract expressionism that ruled the art world in the late-1950s. Karaszewski says: "Tim doesn't make fun of these kinds of things. He understands that there's a lot of heart in these paintings. As an artist himself, he understands what goes into this and why it's important. It's similar to Ed Wood, a character who most people just laughed at. We wanted to concentrate on his passion and figure out a way for people to understand that it's not a joke. That's sort of what this movie is too: Margaret Keane is not a joke and it's a very important story to tell."

Producer Howell wasn't familiar with the Keane art before reading the script. "When I first started to look at it, I was really fascinated by it. I think her earlier work is very sad and has a lot of soul and a haunting quality. It's interesting to see how her work changed over the years, based on her mood, and her later work is much more colourful and brighter, and has a lot more joy in it. I don't think her work is simple. There is a complexity to it and I really love some of it. One of the biggest questions this movie raises is: What is art? It's so subjective, who's to say that something is a masterpiece, who judges that? I think everybody's individual opinion is of value and that's what I think this movie is about. What is good art, what is bad art and who are any of us to judge? If it touches you then surely it's art."

"Art tends to be pretentious and serious," says Alexander, "and we love the idea that in our story people can argue about art and yell at each other. The head critic of the New York Times (Canaday, played by Terence Stamp) hated the Keanes so much and it made him crazy that they were making all this money and on TV and he just wanted to stop them because it was terrible."

Read more about Big Eyes and other films opening this week at www.writingstudio.co.za.