Top stories

More news

Logistics & Transport

Maersk reroutes sailings around Africa amid Red Sea constraints

The Recycled Island Foundation and the WHIM Architecture firm launched the Recycled Park Project in 2014 with the aim of catching plastic waste in Rotterdam’s New Meuse river before it enters the North Sea. Three floating litter traps with nets attached collect litter in the water while volunteers sweep the riverbank.

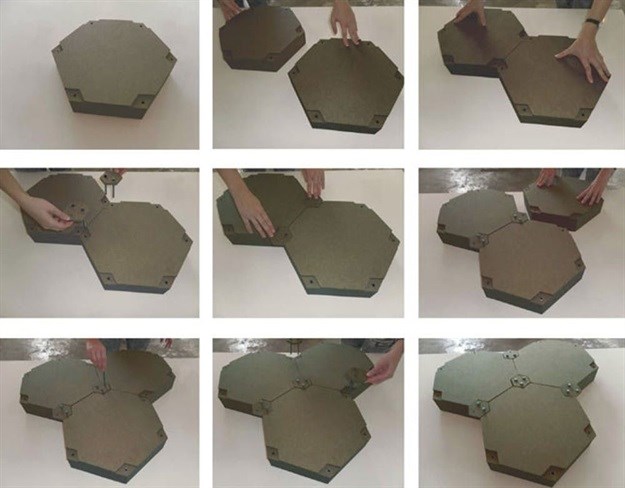

The retrieved plastic is converted into hexagonal building blocks which have been used to build a floating island park in the river itself. The park is open to the community and filled with plants and benches, giving people a new green habitat to enjoy in the heart of the city.

A 140 square metre prototype was opened to the public in July 2018. It’s hoped that five more plastic litter traps can be added to the river, creating an island of at least 190 square metres. If successful, similar islands could be built worldwide, with research ongoing in Indonesia.

The River Meuse carries a huge amount of plastic waste which is exposed after high tide on the river banks. By removing plastic from the river, the more costly and difficult job of removing it from the North Sea is avoided.

Despite the obvious benefits, however, retrieving plastic waste from the river is technically illegal. Waste in the New Meuse River still legally belongs to whoever discarded it, as EU law states that waste may not be abandoned and littering is a form of abandonment. So, the taking and using of this waste in theory amounts to stealing from its most recent owner.

But since there’s no way of identifying to whom the litter belongs and with no way of identifying ownership, it’s socially acceptable for anyone to take and use plastic waste in rivers.

In order to encourage more reuse and recycling, we need to start treating waste as our communal property. A communal approach would encourage a sense of responsibility for waste and ensure that the community reaps the benefits of any solution, such as a floating park.

So how would communal approaches work in practice? There would need to be a clear stage at which waste becomes communal property. This could be, for example, by making contents in specific bins free for people to take and use. For households in the UK, the contents of a bin belongs to the householder until it is removed by the local authority.

It’s not free for others to take and use it, either before, during or after collection, including by the employees of the waste management services. In one legal case, waste management workers for a corporation were convicted of stealing goods from bins collected in the course of their duties. Once waste is collected, it becomes the property of the local authority responsible for managing the waste.

Communal bins would provide an additional benefit if combined with rules that require the contents to stay within the community. Local dumps already exist, but much of this waste is currently being taken elsewhere for landfill or exported to other countries.

If at least some waste were to stay permanently in the communities in which it’s created, people would be faced by the vast amounts of waste they produce and could see the benefits of producing less of it.

The current system of privatising waste is failing to curb the pollution crisis, but with a communal approach, people would have the right to launch creative solutions of their own. We need the freedom to imagine different ways of living with the plastic our modern world accumulates.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()