Top stories

Marketing & MediaWarner Bros. was “nice to have” but not at any price, says Netflix

Karabo Ledwaba 1 day

More news

Logistics & Transport

Maersk reroutes sailings around Africa amid Red Sea constraints

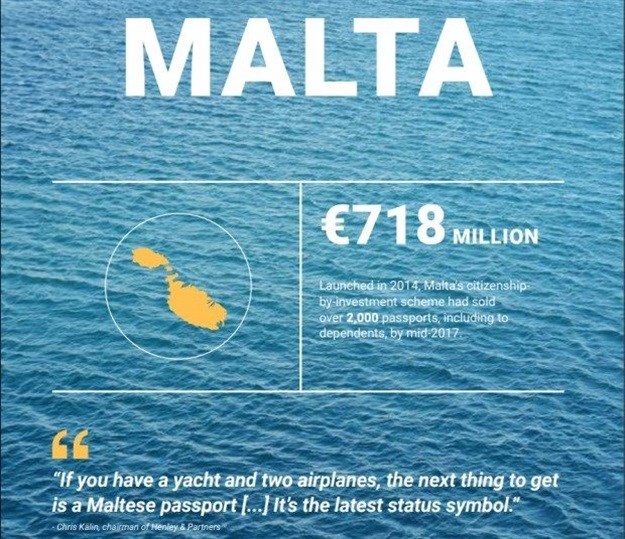

According to a report in the Times of Malta, golden visa schemes globally generate €11.15 billion a year, of which citizenship by-investment schemes (passport sales) represent about €2.6 billion, and residence by-investment schemes over 8 billion. According to industry experts, golden visa schemes are expected to generate as much as €17.17 billion annually in a year or two.

Four EU member states currently sell passports: Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus and Malta and twelve offer residency permits: Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the UK.

In relative terms, the figures for small economies like Cyprus and Malta are impressive. Following a recent reform that introduced an annual cap of 700 naturalisations through its investment programme, Cyprus has the potential to attract €1.4 billion annually, which represents about 7.5% of the country’s current gross domestic product (GDP) levels.

In Malta, the contributions of the Individual Investor Programme (IIP) to the Treasury and the National Development and Social Fund (NDSF) was reported to have risen from €50 million in 2015 to €172 million in 2016 (0.5 and 1.7% of the GDP, respectively). In 2017, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expected these inflows to reach €230 million, or roughly 2.1% of the GDP and 5.4% of fiscal revenue.

This month, Malta’s passport scheme has been slammed by an international report, which highlighted the need for the island to adequately address the programme’s reputational and money-laundering risks. European getaway: Inside the murky world of golden visas was published on Wednesday, 10 October by Transparency International and Global Witness 2018, with research supported by the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium.

The report looked at various aspects of the schemes offered by Cyprus, Malta and Portugal, and the flaws or loopholes in each, stressing that “insufficient due diligence, wide discretionary powers and conflicts of interest” could open Europe’s door to the corrupt.

The report said:

The sale of citizenship – its profits, ethical implications and risks – affects all EU citizens. As this report shows, however, we remain woefully ignorant of how these schemes work, how our governments may be mitigating the inevitable risks that arise from selling mobility to the ultra-wealthy, and where their investment is ultimately going. The debate, however fierce, cannot advance toward productive results without transparency and consultation regarding the risks and rewards, for the EU, of selling citizenship and residency.It warned that in spite of a four-tier due diligence process in Malta, government officials enjoyed wide discretion on eligibility, noting that applicants who have criminal records or are subject to criminal investigation may still be considered due to “special circumstances”.

“Russians who were included on the so-called ‘Kremlin list’ 74 – Arkady Volozh, Boris Mints and Alexander Nesis – managed to obtain Maltese citizenship through the IIP in 2016, raising doubts on the rigour with which the programme manages its due diligence findings,” the report highlights.

“While the Kremlin list, published by the US in January 2018, is not a sanctions list, it does identify Russia’s wealthiest businesspersons who are believed to be close to Russia President Vladimir Putin and who could have been enriched through corruption. Neither has been on record with a response to these allegations. The three Russians were not included in the subsequent sanctions list released on April 6 by the US Treasury.”

One of the loopholes it identified was that that in a number of cases, a cover letter written by Identity Malta to the minister failed to mention potential issues that had been raised in the dossier, which tended to be more comprehensive. The Office of the Regulator communicated these concerns to Identity Malta, but it remains unclear if or what measures have been taken.

Another worrying aspect is that applicants are not required to purchase the passport using their own funds and may rely on a benefactor to make the investment on their behalf. While the benefactor is required to submit a declaration of their sources of wealth and funds, the law does not specifically require the conducting of enhanced due diligence on the benefactor.

“If no additional checks are undertaken, there may be risk of money laundering, as applications of individuals with clean criminal record could be financed by a dubious benefactor using illicit funds,” it said.

The need to foster ties with the island has also resulted in applicants making donations to local charities, however, an approved agent interviewed by the Office of the Regulator suggested that Identity Malta was pointing applicants to specific charities. By the end of 2016, 215 donations amounting to €1,703,700 had been made, and while a list of beneficiaries was published in February 2017, this information is not made regularly available for public scrutiny.

The report also looked at the role of the concessionaire, Henley & Partners, which has been restricted over the years. But in spite of the reduced burden of due diligence, it was still earning the same amount.

As of June 2017, Henley & Partners reportedly earned €19,054,000 from the programme, while Identity Malta, now responsible for the programme’s implementation and administration as well as for conducting and making final decisions on due diligence processes, has received €23,701,500.

“In order for the IIP to contribute to the economy and social development in a sustainable manner, it also needs to increase transparency and accountability in the management of contributions and decision-making, particularly by limiting the discretion of public officials. Otherwise, the programme is at risk of benefiting the few to the detriment of many,” the report warned.