Top stories

More news

Logistics & Transport

Uganda plans new rail link to Tanzania for mineral export boost

"This is the biggest blessing the new South Africa is able to bestow on its citizens," he begins. "You can start out a nobody and become somebody. No longer do our todays define our tomorrows."

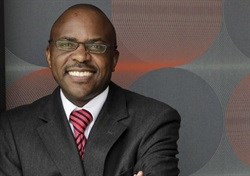

Tshisevhe is sitting in a glass-walled boardroom in Sandton on the top floor of TGR Attorneys, the law firm he started in 2011 with two partners - Sandanathi Gwina and Matodzi Ratshimbilani. From his perch he looks out at the towers of the commercial heart of Africa, shrouded in misty rain today.

"Our Constitution promises us all opportunity, the right to participate economically. If we do not fight for these rights for everybody they remain formal, never practised. We need to be vigilant, we need to exercise those rights, inhabit the spirit of our constitution. They are ideas worth fighting for." He believes that South Africa is losing sight of the hope and promise that gave birth to this democracy, but it is not too late to stop it from straying so far that its people lose sight of who they are.

For 12 years, Tshisevhe has been giving back by lecturing part time at Wits University. The promise of the students with whom he has contact gives him hope for this country's future and insight into what needs work. White students wonder why they should work hard if their skin colour precludes them from opportunity; black students assume that not being a princeling restricts their path to success.

"I give them all the same advice: if you excel who will not employ you? We need excellence, we need our best and brightest to create the environment where we all grow. We are not all equal, but if create a society where the majority are content, we have created a just society."

It is a philosophy that informs the hiring process at TGR. In three-and-a-half years the firm has grown to a complement of 21 professionals, all driven to produce the best work possible. Tshisevhe refers to them as family, one that represents South Africa's demographics.

"There is a common misconception: black firms are associated with mediocrity and white firms with excellence. My legal legacy will be to turn that perception on its head."

Indeed, the 2014 Best Lawyers International list is a peer reviewed listing of excellence published in 65 countries - and it has named Tshisevhe as one of the top four mergers and acquisitions lawyers in the world. He wears his success unassumingly, but you get the sense that he would not step away from a fight.

The offices of TGR Attorneys are all chrome, glass and tile. There is hardly a hint of the African law firm that Gwina, Ratshimbilani and Tshisevhe are building. He nods in agreement and mentions in passing that a change in décor is on the horizon. "We are putting up photographs of Mandela, Tambo, Sisulu, people who embody the spirit we want to create. It is also a way to remember the struggle of those who suffered for the freedoms we enjoy today."

Tshisevhe defies easy classification. His drive has made him one of the best commercial lawyers in the world, but he refuses to work on weekends, time reserved for his family. He believes law is a tool in the fight for social justice but he chose to practice commercial law, despite working alongside activist Professor Jordi at the Wits Law Clinic. He wears tailored suits but says his strength lies in his ability to understand the suffering of the man whose poverty forces him to walk in the rain.

Following matric in 1986, Tshisevhe moved to Johannesburg, where he found work as a shelf stocker at Pick n Pay. He kept working there while studying law at Wits, his wages helping him pay his own way while also supporting his parents.

He tells the story of his first car, a grey Toyota he bought in 1992, and how he was stung by the reaction of people in his home village in rural Venda. "When I got home people called the police because they thought I had stolen the car. In their minds it was the only way someone like me could acquire a car. My life has been about changing the perception that that child or that family are not deserving of success and all that comes with it."

Tshisevhe may sound like a socialist when he talks passionately about social justice, but he is far from it. He enjoys the fruit of his success, the stately home he shares with his lawyer wife, Simone Magardie, and two children, and the home he built for his parents in rural Venda. He celebrates his success because it is built on hard work and determination.

Despite his success, he harbours a minor "what if" concern. What if he had studied high school maths and accounting and gone on to study for the BComm degree that he wanted to do? It's not a thought that keeps him awake - that is more likely to be work - but it does help him to understand that we are all faced with choices, and in the end we need to get comfortable with the path on which we find ourselves.

Greying at the temples, he is developing the distinguished look that comes with age and success. He pushes his frameless spectacles back up the bridge of his nose, explaining that he is the only one in his extended family with poor eyesight, the result of studying in the dimly lit shack he shared with his brother when he first moved to Johannesburg.

He smiles to himself before letting slip: "I would think myself a failure if my children chose to become lawyers." It's not that he looks down on the profession that he excels in, he explains calmly, it's just that his success has given his children the option to be anything they choose to be.

"I want my children to soar, before landing on the highest branch. There is a part of me that thinks choosing to become lawyers would be the easy option. I don't want their lives to be ones of taking the easy choices."

MediaClubSouthAfrica.com is hosted by the International Marketing Council of South Africa (IMC), the custodian of Brand South Africa. The site is a free service for all media professionals - journalists, editors, writers, designers, picture editors and more - as well as for non-profit organisations and private individuals. Its specific focus is on South Africa and Africa.

Go to: http://www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com/