#Mandela100: Centenary of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela's birth - a tribute in poems

Poetry is an under-explored source of additional reflection. Across the arc of Mandela’s defiant resistance to apartheid, through his incarceration, release and presidential term, his life became poetry. The scope of this corpus is enormous, spanning decades and continents alike.

One major anthology, Halala Madiba: Nelson Mandela in Poetry, contains 96 poems from 25 countries. Published in 2005, it includes work by two Nobel laureates, Wole Soyinka and Seamus Heaney. In addition, it features the work of the black revolutionary Cuban poet Nancy Morejón, the Jamaican dub-poet Linton Kwesi Johnson, the Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite, rapper Tupac Amaru Shakur, and Zindzi Mandela — Nelson Mandela and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s daughter.

South African poets, including the late poet laureate Keorapetse Kgositsile, also contribute searing local perspectives. Their texts derive from established traditions of oral poetry, protest poetry and prison poetry in South Africa.

The Island

During the apartheid years, many of the poems in which Mandela appears, imagine or remember him on Robben Island. The island, about 9km west of Cape Town, was used between the 17th and 20th centuries as a prison. Mandela spent 18 of his 27 years behind bars imprisoned on it.

For poets detained as a result of their political activism, the place of incarceration is also the place of writing. Poets imprisoned on Robben Island alongside Mandela, like Frank Anthony and Dennis Brutus, take the Island as their subject.

Dennis Brutus (1924-2009), the coloured (mixed race) political activist pivotal to promoting the ban on South Africa’s participation in the Olympics, was arrested and imprisoned on Robben Island between 1963 and 1965 where he occupied the cell next to Mandela. Brutus invokes Mandela directly as both fellow prisoner and figurehead of the struggle. In the poem “Robben Island” written from exile in 1980, the Island becomes a potent site of memory. The poem begins with a slowly unfolding recollection as details of the past move into focus like a replayed, unspooling film.

Brutus initially evokes the deep intimacy of labouring men bent over the stones in the quarry. The speaker is “anonymous”, while the prisoners recalled are initially “faceless”. Their names and faces only materialise gradually:

I see the men beside mePeake and Alexander

Mandela and Sisulu

The will to freedom steadily growsThe force, the power, the strength

steadily grows.

Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian poet, playwright and Nobel Prize laureate who was himself a political prisoner in Nigeria, addresses the figure of Mandela on Robben Island in the 1988 volume Mandela’s Earth. In his poem “No! He Said”, Mandela assumes mythic status.

The Island is both a geographic location and an imagined space of resistance. In this poem, Mandela is Atlas shouldering the universe, part Colossus, part Prometheus, part Christ.

The poem takes as its starting point Mandela’s refusal in 1985 to accept release from jail in exchange for renunciation of the legitimacy of the armed struggle against apartheid. In Mandela’s obdurateness and unwillingness to break faith with the struggle, he becomes an emanation of the granite fixedness of the island itself.

The poem rejects any sense that the Island has subdued Mandela, as these lines suggest: “No! I am no prisoner of this rock, this island,/ No ash spew on Milky Ways to conquests old or new./ I am this rock, this island.”

Outpouring of poetic celebration

Mandela’s release in 1990 was met by an outpouring of poetic celebration both within South Africa and globally. The Irish poet Seamus Heaney recorded his fierce opposition to the apartheid regime as early as the 1960s. In 1990, he published his play The Cure at Troy – a reworking of Sophocles’ Philoctetes. The concern in the play with injury, betrayal, suffering and reconciliation was widely seen to mirror the conflict in Ireland.

Inspired by Mandela’s release, Heaney later added a chorus to the play, dedicating it to Mandela. In an interview with South African journalist Shaun Johnson in 2002, he makes Mandela’s relevance explicit:

It seemed to me to mesh beautifully with Mandela’s return. The act of betrayal, and then the generosity of his coming back and helping with the city – helping the polis to get together again.

The chorus celebrates Mandela’s release but it does so through the lens of political extremity in Ireland. Mandela’s example is held out as one of miraculous possibility attesting to the possibility of conciliation and reparation.

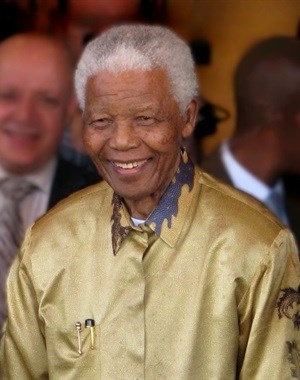

![]() Mandela is no longer with us. Routine invocations of his miraculous or even quasi-messianic status that became part of public discourse following his release have themselves dimmed and lost their usefulness. But, attending to Mandela’s legacy in poetry can help to re-familiarise us with the values he embodied, renewing engagement with the ongoing imperative to oppose racism in the name of political equality, constitutional democracy and economic justice in South Africa.

Mandela is no longer with us. Routine invocations of his miraculous or even quasi-messianic status that became part of public discourse following his release have themselves dimmed and lost their usefulness. But, attending to Mandela’s legacy in poetry can help to re-familiarise us with the values he embodied, renewing engagement with the ongoing imperative to oppose racism in the name of political equality, constitutional democracy and economic justice in South Africa.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Source: The Conversation Africa

The Conversation Africa is an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community. Its aim is to promote better understanding of current affairs and complex issues, and allow for a better quality of public discourse and conversation.

Go to: https://theconversation.com/africa