#PulpNonFiction: Banning flip flops, hot roast chicken and other silly rules

You would be hard-pressed to convince me (or any scientific mind), in retrospect, that banning the sale of books, flip flops, “crop bottom pants”, and hot (but not cold) roast chicken materially improved the health or safety of South Africans in the winter of 2020.

Weird and wonderful rules and regulations are not limited to crisis times though; indeed, if you look, you will find them littering law books across the word. For example, in America, in certain states, it is illegal to carry an ice cream in your back pocket, to serve wine in a teacup, or to serve apple pie without cheese. And in the UK, not only is it illegal to be drunk in a pub, it is an act of treason to put a stamp on upside down.

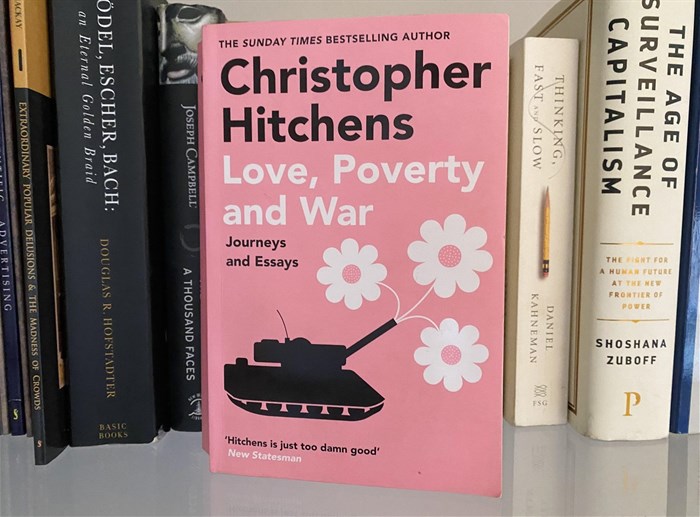

I was reminded of all this as I read Love, Poverty, and War, a collection of essays by Christopher Hitchens. One of the essays in the book detailed Hitchens’ mission to break as many silly laws as possible while visiting New York. This crime spree included stopping to tie his shoelace on a subway staircase to avenge a heavily pregnant woman who had received a fine for resting on one of those sacred stairs; finding a milk crate to sit on, and feeding the local birds a crust of bread.

Sometimes, the law really is an ass.

The real problem with silly rules, however, is not just that petty laws are annoying; but rather that they undermine the legitimate authority of the person or entity issuing and enforcing the arbitrary decrees.

When your government regulates the type of fashion you are allowed to purchase in the name of health and safety, they also, inadvertently, discredit their other more sensible and scientific messages. The subtext the subject receives when they are instructed to obey obviously unnecessary rules is that the authority either does not know what they are doing or even worse, that the authority is abusing their power.

The same risks apply to enforcing unnecessary rules in the workplace. In Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, James C Scott explains that employees can take revenge on arbitrary rules not just by breaking or ignoring them, but worse - by following them to the letter:

“This homely insight has long been of great tactical value to a generation of trade unionists who have used it as the basis of the work-to-rule strike. In a work-to-rule action (the French call it grève du zèle), employees begin doing their jobs by meticulously observing every one of the rules and regulations and performing only the duties stated in their job descriptions. The result, fully intended in this case, is that work grinds to a halt, or at least to a snail's pace.”

Business owners and leaders adapting right now to managing distributed and the remote workforce’s who feel tempted to engage in micromanagement and tight staff surveillance would do well to learn this lesson.

As Billie Eilish sings, “don’t abuse your power”.