About two weeks ago saw the 10th anniversary of the iPhone, marking the mass acceptance of the smartphone. In truth, the technology had already been developed five years earlier. That technology, together with the global roll out of the internet a scant five years previously, have transformed society forever.

Now, news travels at the speed of light. Unfortunately, knowledge travels considerably slower as it requires the application of human reason, if not wisdom.

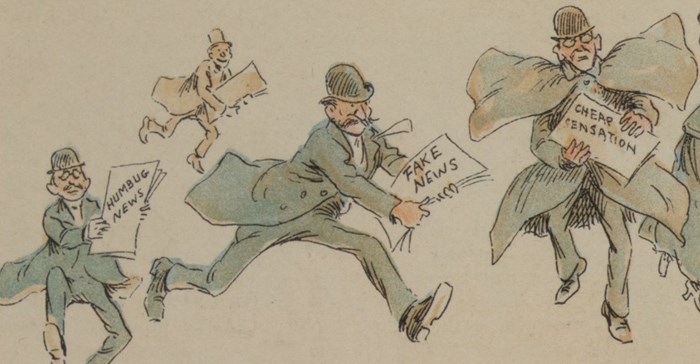

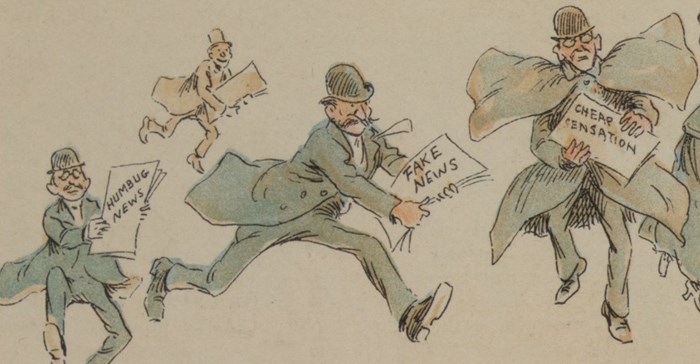

The concerns raised about the rapid spread of fake news is less about its existence (it’s been around for at least 100 years, as the illustration below attests), but rather more the speed with which it disseminates. Wikipedia’s definition: “Fake news is a type of yellow journalism that consists of deliberate misinformation or hoaxes spread via traditional print and broadcast news media or online social media,” confirms it’s deliberate, but its mention of online dissemination means that nowadays anybody can spread lies, not just journalists and spin doctors.

In the last few years we’ve found leaders, politicians and other responsible leaders stating ‘facts’ that are blatant lies, e.g.: “In just a short period of time, we’ve already added nearly one million new jobs,” Trump tweeted on 8 June 2017, whereas the US Bureau of Statistics gives 594k new jobs since January when Trump took office – that’s from page six of Time magazine, 26 June 2017. Needless to say, in South Africa barely a day goes by without similar examples in our daily news.

What is more concerning is not only do they get away without censure (hence implicitly condoning such behaviour), but that it’s spread into the world of reasoned logic that we know of as research.

A definition:

Diligent and systematic inquiry or investigation into a subject in order to discover or revise facts, theories, applications, etc.

-

www.dictionary.comNow, the point about research is that it is founded on clear and rigid rules that should be diligently and systematically applied. In 2011, Scientific American published a paper titled ‘An epidemic of false claims’ where the author John PA Loannidis reported that: “The problem is rampant in economics, the social sciences and even the natural sciences, but it is particularly egregious in biomedicine.” It seems to me that, with the demise of AMPS, fake research is on the rise in South African marketing.

As with fake news, the acceleration of fake research has probably been aided and abetted by the internet and social media. Esomar, the arbiter of international market and opinion research standards, have been alert to this and, in February 2015 published updated key requirements for research practioners (Esomar-GRBN Online Sample Quality Guideline). The standards are mandatory for members of Esomar, and are the result of careful consideration by leading research across the world and, consequently, it is the responsibility of research buyers to evaluate the methodology and processes of non-Esomar member organisations.

Of the 10 key requirements outlined, three are discussed here, as these three have been prominently absent from a number of South African surveys that have come to our attention:

1. The claimed identity of each research participant should be validated

The most critical and frequently abused principle is simply ensuring that each survey is completed by one and the same person. People can have many email addresses, Twitter handles and Facebook personas. Add to this the fact that bots are very sophisticated and can manufacture millions of ‘likes’, tweets, retweets and survey completions. Out of all these possibilities, it’s incumbent on the researcher to assure that a single human being has completed each survey. The most common fault is that a person should not be able to forward the survey to another person and both complete it. If it’s allowed once, why not a thousand times? Failure on this one factor should disqualify any survey from being mentioned on the same page as the word ‘research’, in any discourse.

2. Providers must ensure that no research participant completes the same survey more than once

In online research, there’s usually some incentive to complete a survey, whether it’s cash, or a chance to win an invitation to a prestigious event, there is an obvious temptation for a person to complete the survey multiple times, to increase the likelihood of winning the inducement. This is contrary to the fundamental idea of measurement and compromises any interpretation that can be made. It’s especially bad when a person who has completed the survey is invited to complete it again, repeatedly.

3. Research participant engagement should be measured and reported on

Online research results must be (a term that Esomar guidelines stress), checked for respondent involvement. This involves straightlining, speeding and logical consistency.

Researchers and, more importantly, marketers, have a professional and moral responsibility to guard against falsity of any kind, but especially research that will mislead and misguide decision making.

Author’s note:

This article has been provoked by a number of press releases recently that appear to have derived from online surveys that came to our attention over the past month or two. These surveys were subjected to the tests above. They definitively and abysmally failed the first two and the press releases made no mention of the third.