Top stories

Energy & MiningGlencore's Astron Energy gears up with new tanker amidst Sars dispute

Wendell Roelf 8 hours

More news

Logistics & Transport

Uganda plans new rail link to Tanzania for mineral export boost

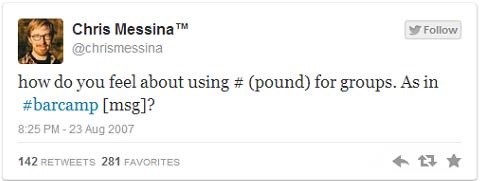

A hashtag is a string of characters that begins with the '#' (hash or pound) symbol. Its primary function is to filter and link related content. Hashtags were first introduced by Twitter in 2007 after Chris Messina, an open source advocate at Google, sent out the following tweet:

Eight years later, we now know social media users reacted positively to his suggestion and the hashtag is ubiquitous across all social media platforms. Messina wanted a 'better eavesdropping experience' on Twitter and believed hashtags would achieve this. They allow us to hone in to what others are saying about a topic or event that interests us, and go even further by allowing us to contribute to the conversation as it evolves.

Hashtags have been used effectively by journalists and lay-persons alike allowing real-time reports on current events. When Cape Town was ravaged by wildfires in March 2015, hashtags flared up as Twitter users tweeted information about their immediate surrounds and requested information from others using #capefire and a host of localised hashtags including #clovellyfire, #kalkbayfire and #muizenbergfire.

Hashtags hold incredible value for brand owners who, if they are able to leverage them successfully, can create a worldwide buzz around their brand. Audi's #WantAnR8 campaign, once dubbed the most successful in Twitter history, began with a Twitter user sharing a tweet using the hashtag along with a message about why he wanted an Audi R8.

Audi responded offering users a chance to drive an R8 for a day simply by Tweeting the hashtag. As the use of hashtags become more common, brand owners and trademark attorneys are faced with intriguing questions.

Can a hashtag be registered as a trademark? And can the use of a registered trademark as a hashtag constitute trademark use or infringement?

In the Eksouzian v Albanese case the parties had previously been in business together making and selling an e-cigarette/vaporiser, which was sold under a name incorporating the word 'CLOUD'. They decided to dissolve their partnership and continue this line of business individually, and in competition with one another. The plaintiff began selling its e-cigarette under the mark CLOUDV, and the defendant used the mark CLOUD PEN.

In terms of their dissolution agreement, each party agreed to restrict their use of the word 'CLOUD' in connection with their products. The defendant agreed only to use the word 'CLOUD' as part of a unitary mark, and the plaintiff agreed not to use a unitary mark which incorporated the word 'CLOUD' alongside a list of terms including 'pen' and 'penz'.

According to the United States Patent and Trade Mark Office's (USPTO) Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP), a 'unitary mark' refers to a mark with elements that are merged together into a single concept that transcends the meaning of each individual component, while a 'composite mark' is a mark made up of separable elements. By example, BLACK MAGIC would be considered a unitary mark, while PROSHOT is merely a composite of two phrases.

The defendant accused the plaintiff of contravening this agreement by, inter alia, using the hashtags #cloudpen and #cloudpenz in its promotional advertisements. The District Court had to decide if

a. these hashtags constituted trademarks, and

b. if they were unitary marks.

The court quickly dismissed the claim on the basis that hashtags are "merely descriptive devices, not trademarks, whether unitary or otherwise".

Despite this ruling, the USPTO has registered many hashtags as trademarks, indicating that they are in some cases capable of serving a trademark's function of distinguishing the goods and services of one entity from those of a competitor. The TMEP states that a '#' symbol does not render a mark distinctive, but clearly it does not consider all marks containing a '#' symbol to be descriptive either.

What the judge seems to be pointing to is that the use of a trademark as a hashtag is descriptive use. In order to establish trademark use, the hashtag must be used to distinguish the goods or services identified by the mark from similar goods or services offered by another. It is certainly true that hashtags are not always used to indicate origin, but that does not mean it is impossible for them to do so.

In South Africa, in order to be registerable, a trademark must be capable of distinguishing the goods or services offered under the mark from the same or similar goods or services offered by others. At the time of writing, there were seven registered hashtag trademarks on the South African Trade Marks register, and 54 hashtag marks in various stages of pre-registration, with 32 of these having been applied for in 2015.

Hashtag marks are clearly on the rise and our courts will have to decide how to classify them soon enough. The fact that hashtag marks have already been registered does however indicate that the South African Trade Marks Office considers them to be capable of distinguishing one going concern from another.

Having said that, simply being registrable does not mean that whenever the mark is used, it is used as a trademark. 'Trademark use' is determined by how consumers perceive the mark.

In Verimark (Pty) Ltd v BMW AG [2007] SCA 53 (RSA), BMW, had alleged that Verimark infringed its rights to its logo mark when it included an image of the bonnet of a BMW, showing its logo, in an advertisement for Verimark's Diamond Guard car polish. The Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) found that this was not trademark use, because consumers would not conclude that there was a material link in trade between Diamond Guard car polish and BMW.

The SCA said that '[w]hat is, accordingly, required is an interpretation of the mark through the eyes of the consumer as used by the alleged infringer. If the use creates an impression of a material link between the product and the owner of the mark there is infringement; otherwise there is not. The use of a mark for purely descriptive purposes will not create that impression but it is also clear that this is not necessarily the definitive test.'

The SCA repeated this sentiment in Adidas AG and Another v Pepkor Retail Ltd [2013] ZASCA 3 and stated that determining whether the use of a trademark in a particular scenario will constitute trademark use is a 'factual issue, which must be determined, objectively, by how the marks would be perceived by the consumer.'

If Eksouzian v Albanese was heard in South Africa, it is likely that the court would have asked whether the use of #cloudpen and #cloudpenz on the plaintiff's advertisement for its e-cigarette would have been perceived by consumers to indicate a material link in trade between the advertised e-cigarette and the defendant, as proprietor of the CLOUPENZ and CLOUDPEN trademarks. This question is considered on a case by case basis, but it seems plausible that a South African court might have ruled that such a material link could be perceived through the use of each mark as a hashtag.

Part of this assessment regards the descriptive nature of the mark in question. If the mark is commonly used to refer to the relevant items, a material link is less likely to be perceived. On the contrary, if a mark is well known, consumers are more likely to make such a connection.

There are two scenarios in which one can use a third party's trademark in the United States. These situations are labelled 'descriptive fair use' and 'nominative fair use'. Trademarks that have a descriptive meaning in addition to their secondary 'trademark' meaning can be used by third parties to describe their products and services.

Nominative fair use allows third parties to use another entity's trademark to refer to that entity's actual goods or services, typically in comparative advertising. In this instance, both parties claimed that their use of their competitors' trademarks as hashtags was nominative fair use, and was done in order to draw attention to their advertisements.

This may have been their intention, but the pivotal point in South African law remains whether or not the consumer would perceive the use as indicating a material link between the goods advertised and the proprietor of the mark.

A related issue which South African courts have recently considered is that of AdWords. AdWords are keywords driving search traffic which Google offers for sale to the highest bidder. Each time a keyword is searched on Google, the successful bidder's advert appears at the top of the search results page even though the AdWord is not necessarily visible in the advert itself.

In Cochrane Steel Products (Pty) Ltd v M-Systems Group (Pty) Ltd, the High Court did not consider M-Systems' bid for the CLEARVU AdWord to be passing off, even though its competitor, Cochrane Steel, complained that it had common law rights to the mark. The court held that there is nothing inherently unlawful about using a competitor's trademark in a manner that is not visible to the consumer and therefore unlikely to cause deception or confusion.

Hashtags, on the other hand, are seen by social media users. Therefore, the assessment of consumer perception involved in the use of AdWords and the use of hashtags will differ. At its core, trademark law aims to protect consumers from being deceived or confused into purchasing goods or services from one entity, thinking they emanate from another.

South African law has established a strong yet flexible jurisprudence governing trademark use and how it is perceived through the eyes of the consumer. When hashtag disputes reach South African courts, they should be well placed to apply established principles. Brand owners can avoid #legalheadaches by doing the same.