#PulpNonFiction: If you can't trust yourself, who can you trust?

As Terry Pratchett put it, “A lie can run around the world before the truth has got its boots on.” Never has this uncomfortable truth about the truth been more true than it is today, in the instant information age, where unwise and ignorant - and downright malicious misinformation can go viral and infect the global narrative, eroding democracies and starting protests and revolutions with the click of a button.

(Especially since, as Hannah Arendt wrote, “Lies are often much more plausible, more appealing to reason than reality, since the liar has the great advantage of knowing beforehand what the audience wishes or expects to hear.” Of course fake news is more interesting than the real deal - it was written with

Too much, too little or just right?

In the past, we had a problem of too little information in too few hands; the result was censorship and top-down propaganda. Today, we have the opposite problem, too much information in too many hands. The result is ubiquitous fake news, only compounded by the rise of digital deep fakes that make it impossible to know if any piece of content, written, photographic or video is what it appears to be.

Of course, both results result in the same end result: no one can trust anything at face value and everything should be assumed to be a lie until proven to be the truth. This is a very messy, very human problem. Is the answer to revert to central control of information, as, for example, the South African Internet Censorship Bill proposes? Or are there less authoritarian solutions we could explore?

As such, over the last few months I have done a lot of reading around mis- and disinformation aka fake news and propaganda, which is undoubtably one of the most significant and most contentious issues of our times.

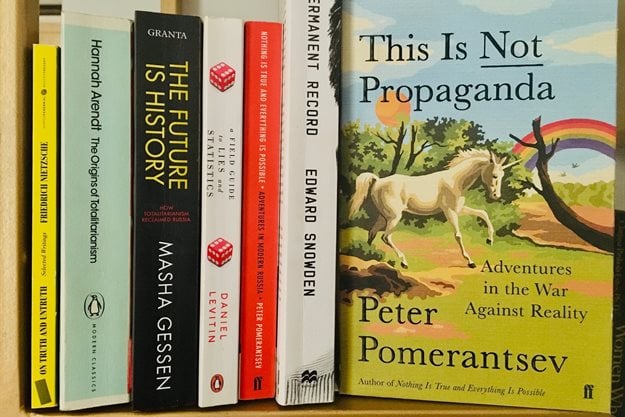

This is not propaganda

The best book I have found so far that wades into these murky waters has to be Peter Pomerantsev’s This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality (which also has, incidentally, a most delightful cover). This book uses real-life stories and deep research to explain the trade offs between central censorship (with the risk of top down propaganda) or decentralised free range information (with the risk democracy-destabilising fake news) and how, untimely, the only way to regain trust and truth in society is for individuals themselves (that is you and I) to realise that the price of freedom of speech and free flowing information is a personal responsibility.

Click clean

We need to start taking responsibility for our own consumption and propagation of information. The same way we have to take responsibility for how the food we eat impacts on our bodies and our health, we are also responsible for how the information we consume affects our minds and our societies.

Clicking on clickbait links, forwarding questionable memes and sharing unverified sources is the information equivalent of an unhealthy junk-food diet at best and downright drug abuse at worst.What is more, we cannot rely on a central authority to make those decisions on what is true and what is good information for us to consume. We all have different tastes and values. After all, all central authorities, be they a government, an algorithm, a business or even a fact checker, all have their own in-built biases and very human failings. There is no singular perfect information authority. We each have to continually decide what we believe is true and understand why we believe so, updating our beliefs as new information comes to light. No one entity or individual can (or should) make up your mind for you.

So click clean. Look after your own mind the same way you look after your own body.