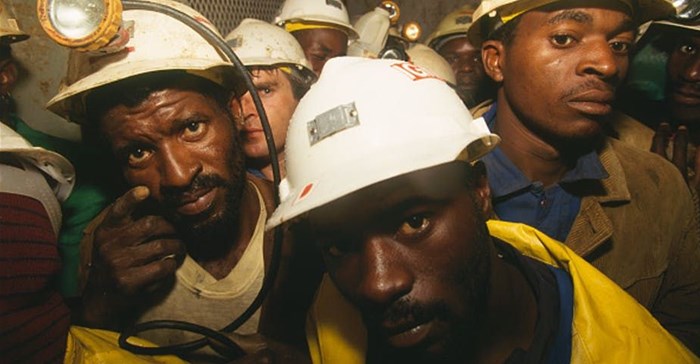

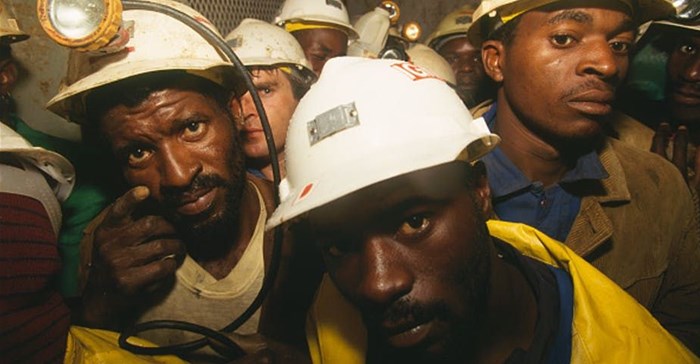

Workers from Kinross Gold Mine, South Africa. Brooks Kraft LLC/Sygma via Getty Images

Mining is an important contributor to the South African economy. It employs around 450,000 people and makes a direct contribution of 8.1% to GDP. Approximately 78% of these people work on gold, platinum and coal mines that are largely underground operations.

Under the regulations easing the lockdown, mining can resume operation at 50% capacity and must provide health and safety protection from Covid-19. But the government guidelines were not binding on employers.

This decision led a trade union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, to take a case to the country’s Labour Court. At issue was the adequacy of the voluntary guidance about the Covid-19 response to protect mineworker health.

The case challenged the preparedness of the sector to protect workers.

The threat posed by Covid-19 on mines is considerable. Working conditions underground are cramped, transportation is in packed cages, and there is a high incidence of respiratory diseases.

The union argued that the hazard posed by the pandemic was too substantial for voluntary guidance and that both the mineral resources minister and the chief inspector of mines had failed to institute the necessary mandatory measures under the country’s Mine Health and Safety Act.

The judge agreed. As a consequence, measures to address Covid-19 are now compulsory for all mines.

One aspect of the union’s argument for compulsory guidance was that worker health and safety representatives appointed under the Mine Health and Safety Act would be unable to hold the employer to account without enforceable standards. Research we have done shows that worker health and safety representatives on South African underground mines are indeed in a weak position. Even with enforceable standards they will face an uphill task.

Case study research we conducted on four underground mines revealed the important, but hugely compromised role of health and safety representatives in a health response.

Health and safety representatives

The powers of safety representatives are largely universal. They include representing workers on all matters related to health and safety, conducting inspections and withdrawing workers from a dangerous workplace. They have the right to training and to resources to support them in their role.

On a large underground mine with more than 1,000 employees there are between two and four full-time representatives per shaft and sometimes hundreds of workplace representatives – those who take on the role of representative alongside his or her job of employment.

These arrangements are subject to agreements signed between the employer and recognised trade unions at a mine site. These agreements typically cover the number and election of representatives and their training and resourcing. Representatives are elected by workers and while the employer must ensure their training and resourcing, there is no requirement for workplace representatives to be paid. Full-time representatives are paid by the employer and this resembles arrangements for shop stewards.

Consultation by the employer with autonomous employee representatives is a central tenet of the Mine Health and Safety Act.

Our research made three major observations about worker representatives when it comes to health issues.

Firstly, that representatives were engaged in activities to address the existing triple disease burden on mines: occupational (lung disease and noise induced hearing loss), communicable (HIV and tuberculosis) and noncommunicable (diabetes and hypertension) diseases.

Workplace representatives acted as frontline health workers responding to the ill-health and emotional problems of production workers. They advised and counselled workers, encouraged visits to the clinic, escorted workers to the surface should they fall unwell, and reorganised workloads in the production team when workers were upset, weak or tired.

Full-time representatives acted as the compassionate voice for workers. This involved, for example, escorting individual workers to face bullying supervisors to address health related problems.

Secondly, representatives took on the responsibilities of the employer too. Full-time representatives took daily instructions (including some about health) from safety management. Representatives conducted inspections, gave education talks and policed the behaviour of workers on behalf of the employer. They also engaged in inappropriate problem solving, such as encouraging workers to use a cloth as a dust mask in the absence of personal protective equipment.

Representatives were often left feeling they would get into trouble with the employer if something went wrong. Representatives who challenged the production imperative by withdrawing workers from a dangerous workplace felt unsupported by the employer. We found approximately 30% of mineworkers who had withdrawn from a workplace went back despite believing it was still dangerous. Workers had little confidence that their health and safety representative could get the workplace fixed.

Thirdly, representatives were dominated on a daily basis by the employer and faced retaliatory employer actions. Supervisors threatened representatives who exercised their powers or had them removed from a workplace. In some instances, they lost their jobs.

We found that worker representatives were not an autonomous voice for worker concerns and therefore could not hold the employer to account. Nor could representatives rely on trade union support. The employer actively discouraged their reporting into trade union branch structures.

Employer appointed service providers, rather than trade unions, provided training and delivered the accredited skills programme. Not one representative in our research knew their powers correctly under the law – even after training. Neither did they have instruments for routine tests, such as for dust, or access to the internet to support their role.

Dangers

For worker representatives to fulfil their role, mandatory standards for Covd-19 protection are a first step. But more needs to be done.

International evidence shows there are broad preconditions necessary to support the effectiveness of worker representation. These include trade union training and support for worker representatives; a supportive steer from the regulator, which could include dedicated guidance about the role and resourcing of worker representatives; and an appreciation by the employer of the autonomous role of representatives.

Mine health and safety has become more complex under COVID-19. A bold step to resource and equip health and safety representatives is now needed.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.