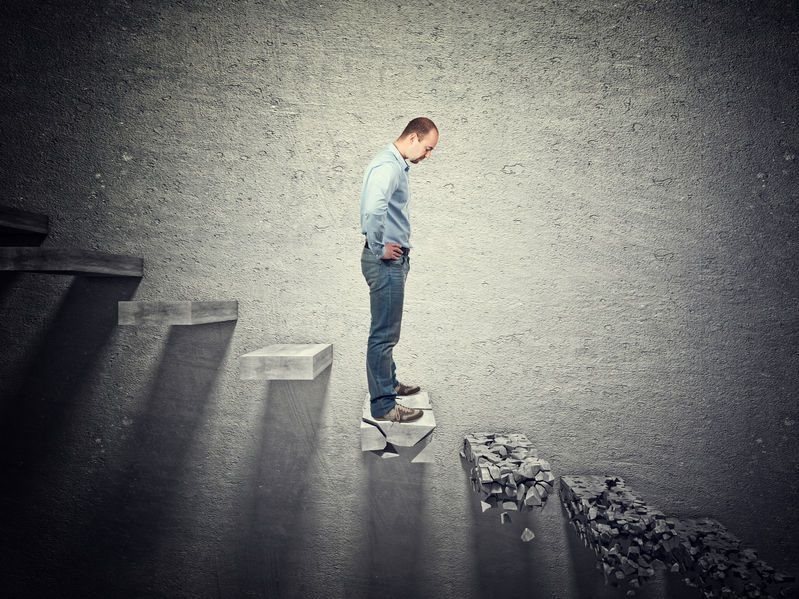

In the recently published Deloitte Africa Restructuring Survey, it was stated that business rescue is experiencing a crisis of trust. The survey highlighted that financial stakeholders often view the actions of business rescue practitioners with a dose of scepticism. The recent judgment of the Pretoria High Court in Commissioner for the South African Revenue Services v Louis Pasteur Investments (Pty) & others highlights issues relevant to the abuse of the business rescue procedure and where business rescue practitioners were taken to task for the manner in which the business rescue procedure had been conducted.

Facts

The applicant, Sars, approached the Court for an order for the final winding up of Louis Pasteur Investments (Pty) Ltd (LPI). Notwithstanding the fact that LPI was both commercially and financially insolvent, the Court also heard an application for rescission of the order converting the business rescue proceedings into liquidation proceedings, as well as an application for the discharge of the provisional winding up order.

LPI had entered business rescue in June 2012, after which a Mr Naude was appointed as the business rescue practitioner (BRP). A formal business rescue plan was adopted in November 2012. Sars obtained judgments in 2010 and 2011 against LPI to the value of approximately R13m, which were never challenged. Sars, in 2013, commenced an audit of LPI’s business, and revised its claim to an amount of approximately R200m. After becoming aware that LPI had been placed into business rescue, Sars instituted proceedings in 2017 to convert the business rescue proceedings into liquidation proceedings. In October 2018, Naude resigned as BRP. After a lengthy delay, a new BRP, Mr Prakke, was appointed in February 2019. In March 2021, an order was granted in terms of section 132(2)(a)(ii) of the 2008 Companies Act (the Act), to convert the business rescue proceedings to liquidation proceedings.

The conversion of the business rescue to liquidation proceedings was opposed by Prakke and LPI on two main grounds. The first of these was that it was not competent for a creditor such as Sars to bring an application for conversion of the business rescue proceedings into liquidation proceedings. The second ground of opposition was that, having regard to the report of Prakke, the business was in fact capable of being rescued despite the fact that the 10 year expiry period of the business rescue plan was in November 2022.

Julian Jones and Caellyn Eedes 31 Mar 2022 Creditor applying to court for conversion of business rescue proceedings

In terms of section 132(2) of the Act, business rescue proceedings may come to an end in three ways. First, where a court sets aside the board resolution or court order that commenced business rescue proceedings, or orders the conversion of business rescue to liquidation proceedings. Second, where the BRP files for the termination of business rescue proceedings. Third, where the business rescue plan falls away, either because it was not adopted or alternatively, because it was substantially implemented. Judge Millar held that a plain reading of section 132(2) confirmed that these were the separate and distinct routes to terminate business rescue proceedings.

The BRP and LPI argued that only a business rescue practitioner can convert business rescue proceedings to liquidation proceedings. Millar pointed out that, while courts have previously said that BRPs may be best suited to apply for the conversion of proceedings to liquidation, that does not mean that only BRPs can make such an application. Indeed, section 132(2)(a) is silent on who should bring the application. As such, it was held that a creditor such as Sars was entitled to apply to convert business rescue proceedings to liquidation.

Furthermore, the BRP and LPI argued that the Sars debt arose prior to the adoption of the business rescue plan. As such, in terms of section 152(2) read with section 152(4) of the Act, the claims could not be enforced except to the extent envisaged in the business rescue plan. Millar disagreed with this contention, pointing out that both those provisions deal with the enforcement of debt which is distinguishable from a conversion application.

Rosalind Davey, Chloë Loubser and Nikita Reddy 8 Apr 2021 Business rescue for 10 years a reasonable prospect of success?

Another argument for the discharge of the winding-up order was that LPI was still capable of being rescued. This was despite LPI being factually and commercially insolvent. In order to evaluate LPI’s argument, the Court examined the business rescue plan, which had two notable features. The first was that holders of LPI’s debentures (with a liability value of approximately R50m) had converted their claims against LPI into equity. Second, the plan envisaged that it would take 10 years to rescue the company. The Court pointed out that this was anomalous in the sense that section 132(3) of the Act sets the default duration of business rescue proceedings at three months. While it is true that most business rescues take longer than the statutory time frame, it is also fair to say that 10 years in business rescue is unusual, to say the least.

Prakke argued that the plan set out a roadmap to solvency, mainly through the liquidation of fixed assets and the litigation of claims against other entities, most notably Louis Pasteur Holdings (Pty) Ltd (LPH), LPI’s holding company. Millar disagreed with this contention, saying that the BRP was effectively winding up the company and not restoring it to an entity that could continue trading, an outcome envisaged by the Act. As the plan did not make provision for the settlement of the tax liabilities, as well as the fact that the LPH was itself in business rescue, the Court held that the extension of business rescue proceedings would effectively allow the payment to some creditors to the detriment of others. Such transactions would not be consonant with the concept of business rescue.

The Court examined the underlying philosophy of business rescue, as set out in section 128(1)(b) of the Act. In this regard, Millar pointed out that business rescue is for the “temporary supervision” of a company. In dismissing the BRP and LPI’s attempt to extend business rescue proceedings, Millar referred to Dr Eric Levenstein in South African Business Rescue Procedure (Lexis Nexis), who emphasises that a drawn-out business rescue plan that is aimed at delaying an inevitable liquidation is undesirable, and ought to be discouraged. Ultimately, Millar came to the conclusion that there was no commercial or rational basis to allow the business rescue to continue. As the Court rightly pointed out, business rescue proceedings are designed to provide a shield for a company, in order to protect it and enable it to trade out of financial distress. Business rescue proceedings cannot and should not be used by companies or BRPs as a sword to keep creditors at bay, without regard to whether or not there is a realistic prospect of success.

Implications for business rescue practitioners

Illustrating its displeasure with the manner in which the business rescue proceeded, as well as the inappropriate opposition to the liquidation application, the Court mulcted the BRP (Prakke) with a personal costs order. The judgment lambasted the BRP’s approach to this litigation, implying that it amounted not only to an abuse of business rescue procedure, but also to an abuse of the Court.

This should be a warning to all BRPs who conduct litigation in a dilatory manner that such behaviour will not be tolerated. More importantly, it is a clear indication that courts will not hesitate to punish BRPs who act contrary to the purpose and objectives of business rescue.

Judgments like this one will go some way to restoring public trust in business rescue and will provide support to counter the proposition of there being a “crisis of trust” in South Africa’s business rescue procedure.