Top stories

EntrepreneurshipHow SMEs can build AI-ready businesses starting with the right technology foundation

Sudesh Pillay, WhyMAcForSME 16 minutes

More news

Logistics & Transport

Uganda plans new rail link to Tanzania for mineral export boost

As a result of this democratisation, journalists are struggling to adapt to this new reality, where they compete daily with a larger society that has blurred the lines between creators and consumers of news.

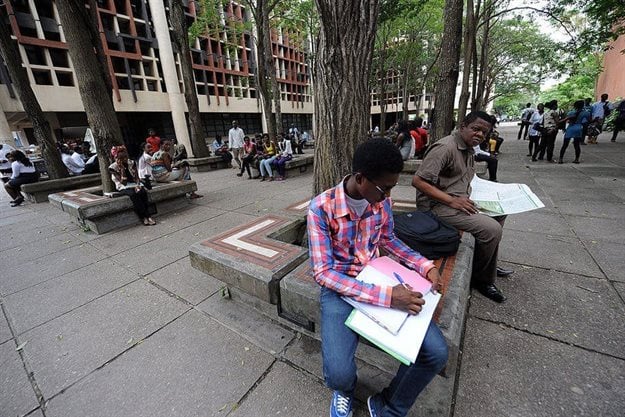

Constant changes in the profession have raised interest in the quality and relevance of journalism education. In these times, university journalism education is becoming increasingly important in shaping journalism practice. Every year, there are more people who take on journalism, armed with formal education and degrees.

There are countless debates about how journalism should be taught and learned in formal spaces. Policy makers, journalism professionals, students, educators — everyone is asking questions about the way forward.

Stakeholders are becoming more interested in how journalism is taught and learned in the university.

A number of journalism studies show that tertiary qualifications are important for journalists around the world. Advancement in tech have brought rapid and radical changes to journalism. This has ramped up pressure on journalism training institutions, as schools struggle to keep up with industry changes.

The challenge is this: while the media industry is very welcoming to fast changes, journalism training institutions are primarily conservative spaces, stuck in their ways.

In 2019, communication educators, media and communication professionals, and industry regulators submitted a new curriculum for Nigerian communication studies to the National Universities Commission.

This was done for quality assurance purposes. This proposal was created to unify and standardise a consistent curriculum for communication and journalism education. The submission received widespread support and backing from industry professional groups and all the relevant regulators.

The grand plan was to unbundle what was known as “mass communication”. This will give way to seven degree-awarding departments in all universities. They include Journalism and Media Studies, Public Relations, Advertising, Broadcasting, Film and Multimedia Studies, Development Communication Studies, and Information and Media Studies. While this proposal holds promise in upgrading media education, many local universities are yet to adopt and implement it.

Over the years, multiple studies focusing on improving journalism training institutions have been conducted. The core focus is usually to design a way for these institutions to adapt to today’s reality. The aim is to quickly upskill, embrace new industry developments and maintain their relevance to the journalism industry. But most of the studies were incomplete. They approached the problem by prioritising the perspectives of the educators and professionals. Students, the recipients of these changes, were never consulted.

My study aimed to fill this gap. These are uncertain times for journalism. The industry keeps changing fast. What is the place of formal journalism education? Especially when traditional media jobs are shrinking as digital media soars.

Only 53 (18.2%) out of 292 student participants in my study identified a connection between their studies and the reality of the industry. They were up against 66.1%, who stated that their learning institutions were deficient. The interviewed students pointed out the gaps in skills, equipment and the overall understanding of what journalism means.

This in no way suggests that a university journalism education is worthless. All the students agreed that they still placed a high premium on the knowledge acquired in the university.

Tech-enabled digitisation is radically altering global media spaces. Newsroom jobs continue to disappear. The relationship between journalists and their audience is an uneasy one. More people are content creators today.

Yet my study results uncover an inherent paradox in journalism education.

Multiple studies and reports show that digital is the dominant medium in today’s media ecology. This growing influence is underpinned by the sporadic growth and yearly increase in digital media revenue.

The internet has been a game-changer. Google and Facebook now control almost all media advertising. The ad-dependent traditional media business structure is struggling, as revenues fall and vanish. According to a recent report, between 2015 and 2018, online advertising revenue recorded an unprecedented 25% to 39% growth. According to the report, even though this growth will slow down in the coming years, online advertising in Nigeria will generate $133 million in revenue.

Here’s the paradox: despite the recorded and predicted influence of digital technologies, over half (51%) of the participating students in my study still wanted careers in traditional media houses. These students chose to study mass communication in Nigeria, expecting to work in the traditional media organisations. They had dreams of finding jobs in television, radio, newspapers and magazines.

Only a meagre 9.6% of students nursed dreams of working in digital media organisations.

It shows that in spite of digital media’s supremacy, Nigerian students still believe in the traditional conception of journalism. This suggests a deficiency in journalism education in the country.

As media jobs shrink globally, students need to be adequately prepared for real-world success. My study shows that the first step is for educators to focus on changing student attitudes towards digital media. The world is in a state of media convergence. All the lines are blurring. Journalism education needs to reflect that.

The future of journalism is online, backed by rapidly improving tech and content formats. Journalism training institutions in Nigeria should focus on student orientation. And with that, teach skills that will make these students compete favourably upon graduation.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.