Top stories

More news

Marketing & Media

Ads are coming to AI. Does that really have to be such a bad thing?

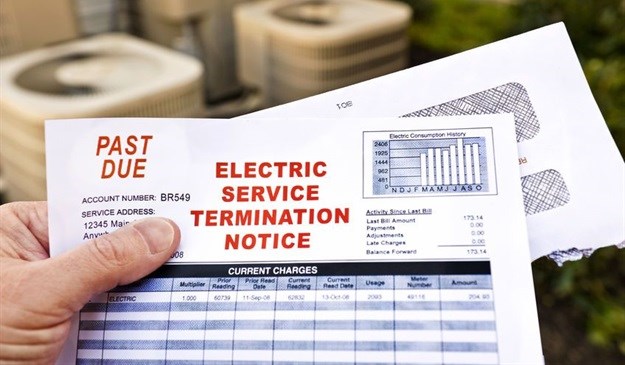

Several municipalities (Tshwane, Ethekwini and Ekurhuleni) have argued in the Constitutional Court in the ‘New Ventures’ matter that it is lawfully permissible for a municipality to attach and sell a purchaser’s property in order to satisfy debt owed to the municipality by prior owners of that property. The municipalities argued that this right was given to them in terms of section 118 (3) of the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 2.

To support this argument, the municipalities claimed that it was lawful to hold the purchaser liable for the historical municipal debts of prior owners, partly because the purchasers should have been aware of the debts before they took transfer of the property.

It was argued that a purchaser who did not want to be liable for these debts could just stop the transfer or sue the seller for damages. In this context, the question arose as to whether any party was under an obligation to make the purchaser aware of the historical municipal debt.

The applicants in the Constitutional Court consisted of a number of municipal consumers, who were aggrieved by the view of the Tshwane and Ekurhuleni municipalities. They contended that (properly understood) the right of the municipality to attach and sell the property in order to satisfy historical municipal debt did not survive transfer, and that once transfer has passed to the purchaser, he could not be held liable for the debt of prior owners of the property. They argued further that (if the court found that the municipalities’ rights to attach the property for the debt of prior owners did in fact survive transfer) that this was unconstitutional because it violated the right of the purchaser to property in terms of section 25 of the Constitution.

In relation to the issue of whether there is a duty on a conveyancer, the applicants argued firstly that it makes little sense to compel a conveyancer to disclose the historical debt to the purchaser, because the purchaser has already purchased the property and there is not much that can be done by the purchaser at this point to escape the liability.

The applicants argued secondly that if section 118(3) was interpreted in the manner that the applications contended for (which was that section 118(3) creates an ex lege or automatic right in favour of the municipality to be paid by the seller for all outstanding historical debt before transfer) that the conveyancer is accordingly legally obliged to take amounts paid into the conveyancer’s trust account from the proceeds of the sale of the seller’s property and use that to settle the historical debt before transfer, thus ensuring that transfer passes without any historical debt being attached to the property.

The Banking Association of South Africa (‘BASA’) was admitted by the Court as an Amicus (‘friend of the court’) to make submissions to the Court about how the law in question affected bondholders. BASA submitted that the ability of a municipality to hold the purchaser liable for the historical municipal debt of prior owners was an unconstitutional infringement of the Constitutional property rights of the bondholder concerned. BASA did not enter the fray relating to duties on parties to disclose.

TUHF was also admitted by the Court as an Amicus to make submissions in relation to how the law affected bondholders. The nub of TUHF’s submissions was that interpreted and applied as contended for by TUHF, section 118(3) was capable of a lawful construction that did not offend any rights of any party.

If a municipality is required to perfect its hypothec by approaching the court to obtain an attachment order, and only thereafter can it register the attachment against the title deeds of the property at the Deeds Office (which will prevent transfer from the seller of the property to the purchaser until such time the municipal debt has been paid in full) the purchaser is protected. The municipality’s failure to perfect its hypothec before transfer would mean that the property would pass to the purchaser free of the burden of any historical debt.

Although TUHF refrained from dealing directly with the issue of whether there is a duty upon any party to disclose the historical debt to the purchaser, it can be inferred from TUHF’s argument that there is no such duty, because the purchaser is not affected by the historical municipal debt if section 118(3) is interpreted and applied as contended for.

The Johannesburg Attorneys Association (JAA) made an application to the Court after the hearing of the matter to be admitted as an Amicus and to make submissions to Court in relation only to the issue of whether there is a duty on conveyancers to disclose the existence of historical municipal debt attached to a property to the purchaser thereof.

The JAA’s submissions related only to the situation where the Constitutional Court found that a purchaser could be held liable in some or other manner for the historical municipal debts of others, because this is the only situation in which such a duty could conceivably arise.

Its submissions can be summarised as follows:

This would mean that, applied to the present situation, when a conveyancer becomes aware of historical municipal debt that will not be paid at the date of transfer, unless the seller of the property gives the conveyancer consent to bring this to the purchaser’s attention, the conveyancer is conflicted because he or she owes a duty of confidentiality to the seller, but also owes a duty to the purchaser to act in that purchaser’s best interest (and the conveyancer cannot in both parties’ best interests simultaneously).

As a result, in such a situation the conveyancer would be conflicted and would need to withdraw for one of the parties (which is inevitably the purchaser). The purchaser would then be referred to another attorney and the conveyancer would ordinarily continue to represent the seller and to conclude the transfer process.

As support for this contention, the JAA pointed out that a conveyancer who finds out that there is another type of problem with the property (like damp or a leaking roof) is not duly obliged to share this information with the purchaser but must act as if he or she were conflicted as described above. The situation with historical municipal debt attaching to the property is no different and conveyancers should not be treated any differently in relation to this issue.

The judgement of the Constitutional Court in this matter is expected to be handed down in a mere matter of months. If the Constitutional Court finds that purchasers cannot be held liable in any way for seller’s historical debt, it is unlikely that the Constitutional Court will consider the issue of where such a duty lies (if indeed it lies anywhere at all). If, however, the Constitutional Court finds that there is a way in which purchasers can be held liable for historical municipal debt attached to the property, then it is likely that we will see the Constitutional Court consider the issue of on whom such a duty lies, as the extent of that duty.