South Africa has a unique opportunity to become the global leader in the regulation of warranties for medical devices.

Throughout the world, legal cases against pharmaceutical companies that manufacture medical devices such as implants for treatment of specific conditions are on the increase, as patients are not always properly informed about how the device works, what its intended purpose is, and, most importantly, how long it will work effectively.

A major problem leading to the increasing law suits stems from a lack of information for patients on what to expect from a product and the patient’s own, sometimes unrealistic, expectations.

When it comes to consumer products – which are covered in South Africa by the Consumer Protection Act (CPA) – different remedies are available for consumers if they are unhappy with the product. For example, a consumer buys a product or pays for a service. The manufacturer guarantees that the product should work as intended, and, should there be a problem, the customer returns the defunct product for a replacement or a refund within specified time period prescribed in the CPA.

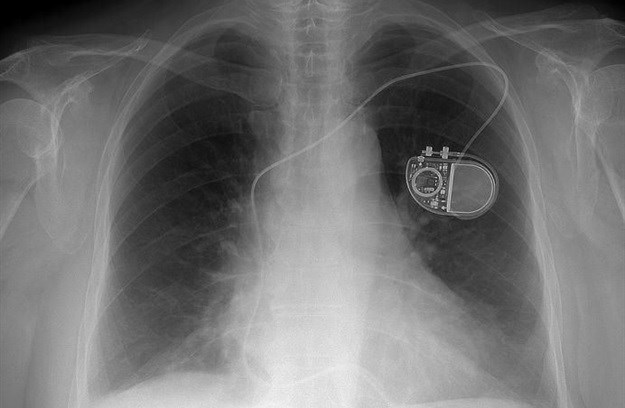

With medical devices – which often include implants that require surgery – it is not that simple. Medical devices are designed and implanted by highly trained medical personnel.

The patient – as the consumer – has no way to know what to expect from the implanted medical device. If things go wrong, patients can experience great discomfort or further health problems, which may require costly surgery to correct. As a result, some patients may then sue both the medical practitioner and the manufacturer of the device.

Necessary regulation

It appears that, besides Poland, no other Medicine and Medical device Regulatory Authority in the world currently legally requires warranties for medical devices. The Polish requirement link specifically to their national health system and was imposed, among other things, with the aim to limit the risk for costly legal suits as a result of defunct devices or associated medical negligence by the medical practitioner who performed the implantation procedure.

Some pharmaceutical companies have warranties for their products, but there is no set standard for what is required in the warranty, and they are often quite vague. The information widely required and which must be included on the label or packet insert of the product is the instructions for use, the intended use of the product, potential side-effects, composition of the device etc. This is regulated and set out in the Regulations under the Medicines and Related Substances Act and provides quite detailed information in this regard. Warranties, however, do not form part of the required information.

The difficulty with warranties for medical devices is that no single device works exactly the same for every person. Due to the complex nature of the human body – and the physical and physiological differences between people, a device that works for 10 years in one person, might work for only five years in another person. This makes it difficult for a manufacturer of a device to accurately spell out what a patient can expect from the device.

The situation can be further complicated when a doctor implants a device for a purpose other than what it was designed for. This has happened under strictly controlled conditions and led to great success for many patients – and to the development of a number of great new medical inventions. But when it goes wrong, the patients usually point a finger at the device manufacturing company.

Having a warranty would be useful in setting out the specific conditions and reasonable expectations for use of a device. It will also ensure that there is clear understanding relating to responsible use and who will be liable in specific circumstances should a defect of the product occur. When a doctor uses the implant for a purpose that it is not designed for, the onus should be on him or her to fully inform the patient of what he or she is doing, and why.

Warranties could also be established according to each risk category a medical device is registered in. The higher risk category the device is registered in would determine the type of warranty required for that device. This will link with the current requirement for safety and performance of the medical device which form part of the Conformity Assessment of the South Africa Health Products Regulatory Authority.

A patient needs to be able to give “informed consent” to any procedure done. If they do not understand what the device is intended for and what the potential side effects or associated risks of the implant procedure is, it is impossible for them to be said to have made an informed decision.

Potential role of the NHI

South Africa currently stands on the brink of launching a new public health system, the National Health Insurance (NHI). The NHI Bill have been presented to the public for comment on 21 June 2018 by the Minister of Health.

This presents us with an ideal opportunity to – like with our Constitution and other acts like the National Water Act – take the lead in the world and come up with a new legal framework that would set a new global standard insofar it relates to how warranties within the Medical device Industry is approached and managed on a long-term basis.

The introduction of a warranty is a win-win for all parties involved and can save the country, the manufacturers and doctors millions of rands in legal costs. Health authorities and practitioners in South Africa already face significant numbers of law suits, due to negligence claims for a variety of reasons. If we do not carefully consider regulations on the requirements of warranties for these products, we can expect these claims to drastically increase in the future – at great expense to the taxpayer.

We are standing on the brink of a great opportunity. All we need to do is to take it.