Writer-director Wanuri Kahiu is part of the new generation of African storytellers whose second feature film Rafiki took six years to reach the big screen. With the support of numerous international funders and the participation of six co-producers - led by South African production company Big World Cinema -pre-production began in December 2016.

Rafiki was the first Kenyan film in Official Selection at the Cannes Film Festival (Un Certain Regard). The film was shot over four weeks in a Nairobi housing estate and a few other city locations in 2017. With the exception of the four foreign HODs, the entire crew was Kenyan and based in Nairobi.

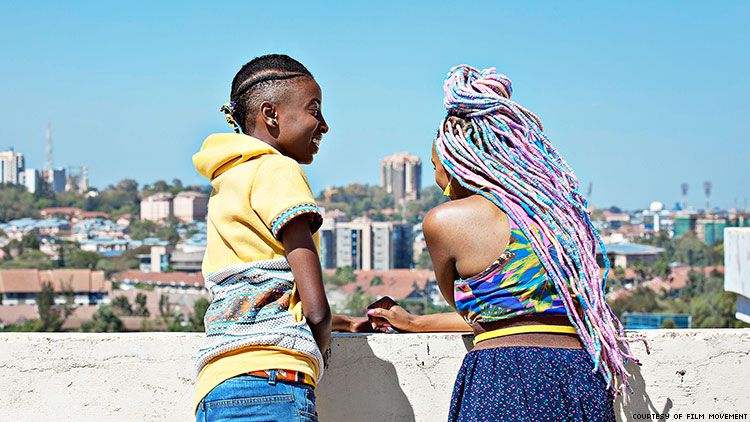

Rafiki is a women-led film with a female director, writers, HODs, crew members, trainees, and soundtrack artists. In the film “Good Kenyan girls become good Kenyan wives,” but Kena and Ziki long for something more. Despite the political rivalry between their families, the girls resist and remain close friends, supporting each other to pursue their dreams in a conservative society. When love blossoms between them, the two girls will be forced to choose between happiness and safety.

The story and its creation is a celebration of young Kenyan women working in the creative economy.

Rafiki was banned by the Kenya Film Classification Board (KFCB) “due to its homosexual theme and clear intent to promote lesbianism in Kenya contrary to the law.” The KFCB warned that anyone found in possession of the film would be in breach of the law in Kenya, where gay sex is punishable by 14 years in jail. The ban raised international outrage by the supporters of LGBT rights.

Wanuri Kahiu sued Kenya’s government to allow the film to be screened and become eligible to be submitted as Kenya’s entry for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 91st Academy Awards. Although the Kenyan High Court lifted the ban on the film, allowing it to be screened in the country for seven days, therefore meeting the eligibility requirements, the film is still banned in Kenya.

Wanuri Kahui

She talks to Daniel Dercksen about the film’s title, creating intimate scenes and LGBTQ+ rights in Africa.

What was the starting point for the film?

I was in my late teens when I first saw a film about young Africans in love. Before that, I had never seen any Africans kiss. I still remember the thrill, surprise and wonder and how the film disrupted my idea of romance. Before then, affection was reserved for foreigners, not us. To imagine that it was normal for Africans to hold hands and kiss on screen was astonishing. Years later, when I read Jambula Tree by Monica Arac de Nyeko, I was caught off guard again. As a romantic, I had to bring to life the tender playfulness of the girls in Jambula Tree and, as a filmmaker, it was vital to show beautiful Africans in love and add those memories to cinema.

Can you explain the title of Rafiki?

‘Rafiki’ means friend in Swahili and often when Kenyans of the same sex are in a relationship, they forgo the ability to introduce their partners, lovers, mates, husbands or wives as they would like and instead call them ‘rafiki’.

How did you find your two actresses as it must have required a great deal of sensitivity and a certain amount of secrecy?

I met Samantha Mugatsia first. She was at a friend’s party and she looked exactly the way I imagined Kena would. I didn’t know anything about her but soon found out she was a drummer. I was excited when she agreed to come in for an audition and even more so when she agreed to play the role. I knew what it meant to accept a role like this in Kenya. It meant a commitment to uncomfortable conversations with friends, family and possible opposition from the government. However, Sam did not waiver – she committed to the project and lovingly brought Kena to life.

Sheila Munyiva came into the audition full of the joy of living. She was full of charm and curiosity and her portrayal of Ziki was the perfect match for the more even-tempered and responsible Kena. Sheila was initially hesitant to take the role, but a close queer friend reminded her of the importance of being seen and acknowledged, so she agreed.

How did you manage to create the intimate scenes?

The experience we want to communicate is the incredibly soft yet awkward newness of first love and the willingness to risk everything and choose it. To do that, we allowed for awkward silences, held gazes, improvised dialogue and fluidity of movement between Kena and Ziki.

When creating that world, we referenced artists like Zanele Muholi, Mickalene Thomas and Wangechi Mutu whose work expresses femininity, strength and courage. We hoped to reflect these attributes in the film and infused the scenes with the immediacy of the vibrant Nairobi neighbourhood we were in. Production designer Arya Lalloo created a maximalist, lo-fi, hybrid aesthetic by mixing lots of prints and textures – from traditional Kenyan and other African cloths to mass-produced fabrics, furniture from different periods and styles and employed bold, bright and varied palettes.

How did you choose your locations and how important is that for you?

We set the film in a lively, upbeat neighbourhood in Nairobi. Once we knew the neighbourhood we wanted to shoot in, we re-wrote the script to suit it. The location we chose is a large, tumbling housing estate with churches, schools and shops – all within a perimeter wall that opens out to a dam on one side. It is the kind of place where everybody knows everyone else and privacy is a luxury. We also wanted the neighbourhood to reflect a cross-section of Nairobi people, from boda (motorcycle) drivers to competing politicians and gossiping kiosk owners. In its bright, noisy, intrusive way, this neighbourhood was the perfect antagonist to the quiet, intimate, secret spaces the girls tried to create.

What is the message of the film?

Making a film about two young women in love challenges the larger human rights issues associated with same-sex relationships in East Africa. Over the past five years of developing this film, we have seen worrying developments in the anti-LGBTQ+ climate in East Africa. Local films and international TV shows have been banned because of LGBTQ+ content. This has stifled conversations about LGBTQ+ rights and narrowed the parameters of freedom of speech. My hope is that the film is viewed as an ode to love, which course is never smooth and as a message of love and support to the ones among us who are asked to choose between love and safety. May this film shout where voices have been silenced.

LGBTQ+ rights in Africa are extremely limited. People face discrimination, persecution and potentially even death but recently they have begun fighting for a place in society. Do you hope to make a difference with your film?

While filming, we challenged deep-rooted cynicism about same-sex relations among the actors and crew and continue to do so with friends, relatives and the larger society. Rafiki brings to the forefront conversations about love, choice and freedom, not only freedom to love but also the freedom to create stories. We hope this conversation reminds us that we all have the right to love, and the refusal of that right through violence, condemnation or law violates our most fundamental raisons d’être: the ability for one human being to love another.

Rafiki opens at cinemas on 31 August 2019

For the latest and upcoming South African films, visit: writingstudio.co.za/south-african-filmmaking