Over a period of 21 months, Eskom's coal-fired power plants belched pollutants that exceeded South Africa's already weak air quality standards close to 3,200 times, sometimes by as much as 15 times the legal limit.

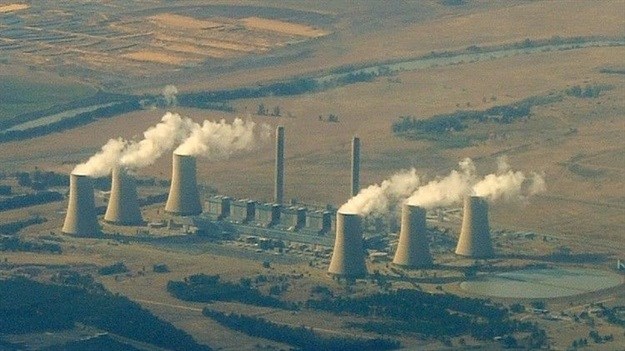

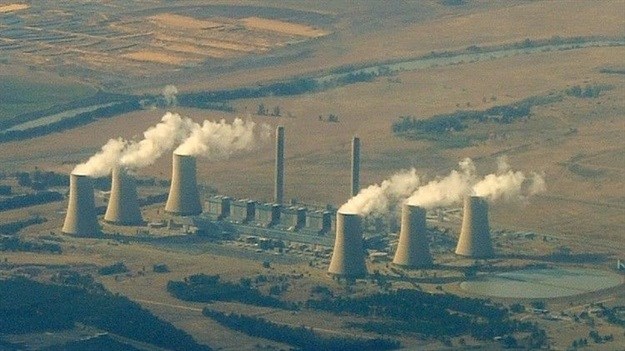

Eskom’s Lethabo power station in the Free State. Photo: Simisa Bearbeitung (Auschnitt, Farben): Pechristener via

WikimediaThe excessive emissions include particulate matter (PM), sulphur oxides (SO2), and oxides of nitrogen (NOx).

The figures – a conservative estimate drawn from the power utility’s own monthly air quality reports, as submitted to environmental authorities – show that nearly all its coal-fired plants are possibly operating illegally and that Eskom’s pollution control measures are not working. Many of the excessive emissions were frequent at particular plants.

Eskom acknowledges there are periods when statutory emission levels are exceeded. However, it argues, this does not constitute illegal non-compliance. Excessive emissions often arise from plant start-up, shut-down or “upset conditions”, which are unplanned, unexpected or sudden incidents. A grace period of 48 to 72 hours is allowed for this in terms of its Atmospheric Emission Licenses (AEL).

Eskom denies that there have been thousands of emission standard violations and says the count is “significantly overstated” because of “a number of errors”.

The new findings were made by US coal plant expert Dr Ranajit Sahu, who was commissioned by the Life After Coal campaign, a joint campaign by Earthlife Africa Johannesburg, groundWork, and the Centre for Environmental Rights. The campaign is dedicated to: “Discouraging investment in new coal-fired power stations and mines; accelerating the retirement of South Africa’s coal infrastructure; and enabling a just transition to renewable energy systems for the people.”

In his report, Eskom Power Station Exceedances of Applicable Atmospheric Emission License Limit Values for PM, SO2 & NOx During April 2016 to December 2017, Sahu explains that he reviewed monthly monitoring reports from 14 of Eskom’s 15 coal-fired power stations over 21-months. (Kusile was excluded from the analysis as the power plant only came on-line in August 2017.)

Conservative conclusions

“My conclusions are conservative and underestimate the true scope of the problem because I did not have access to clear and comprehensive data,” writes Sahu. “Because the applicable limits in the Atmospheric Emissions Licences (AEL) are quite lax compared to those recommended by the World Bank Group, or those adopted by China, for example, having any excessive emissions of the AEL limits is very troubling.”

“Even perfect compliance with AEL limits allows for discharges of pollution at unhealthy levels,” writes Sahu. He notes also that these excessive emissions are even more troubling since most of these plants are located in areas that are already significantly polluted, such as the Mpumalanga Highveld Priority Area.

Sahu also observed that he did not see evidence that the power station operators were using the monthly reports to identify the cause of the high pollution levels in order to take mitigating action.

The Life After Coal campaign said that if Eskom could not comply with South Africa’s already-weak minimum emission standards, the offending power stations should be decommissioned “and an inclusive, transparent, and just transition plan put in place to support workers and their families”.

Responding to the report, Eskom said it “will evaluate the deficiencies picked up by Dr Sahu and address these to ensure that reported information is clear, accurate and in line with the requirements of the licensing authorities”.

It has been calculated that air pollution from coal-fired power stations is costing the country more than R33bn a year in health-related costs, and that the human rights of millions of South Africans are being violated with at least 2,200 people a year dying prematurely from air pollution-related illnesses like bronchitis and asthma.

Article originally published on Groundup.