After birth, the developing brain is largely shaped by experiences in the environment. However, neurobiologists at Yale and elsewhere have also shown that for many functions the successful wiring of neural circuits depends upon spontaneous activity in the brain that arises before birth independent of external influences.

Now Yale researchers have shown in research published online 18 December in the journal Nature Neuroscience that the timing of this activity is crucial to the development of vision - and perhaps to other key neural processes that have been implicated in autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders.

"This spontaneous activity is not dependent upon external sensory stimuli," said Michael Crair, the William Ziegler III Associate Professor of Neurobiology and associate professor of ophthalmology and visual science and senior author of the paper. "We want to know where this activity comes from and how does it work."

Optogenetics

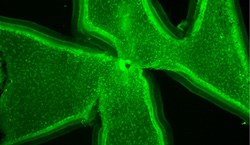

Yale researchers tried to interfere with this spontaneous activity in neonatal mice through a technique called optogenetics - or the manipulation of brain cells genetically engineered to be activated by light. The Yale team showed that proper wiring of connections between the eye and brain depended upon exactly when this spontaneous activity occurs. When the researchers simultaneously induced retinal activity in both eyes of a neonatal mouse, they found the visual connections did not develop properly. However, when they induced activity first in one eye and then the other, neural connections were unaffected or even enhanced.

Crair said that rhythmic spontaneous activity has been implicated in proper development of many brain areas, including the cortex, cerebellum, and spinal cord. He said it is possible that a disruption in the timing of this spontaneous activity could play a role in a host of developmental disorders.

"The genes thought to be involved in autism involve the formation and function of brain synapses and neural circuits, and that is exactly what is getting messed up when we interfere with brain activity early in development," Crair said.

The research was funded by grants from the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health, Research to Prevent Blindness and the family of William Ziegler III.

Yale co-authors of the paper are Jiayi Zhang, James Ackman and Hong-Ping Xu.

Source: Yale University