South Africa sets aside more money for Covid-19 but lacks a spending strategy

The required health system response to Covid-19 broadly falls into these two areas: prevention and treatment. The two are closely interlinked. And there are severe shortcomings in both.

On the prevention side, interventions include social distancing as well as rapid testing, contact tracing and quarantining. These require massive upscaling to have a preventive effect.

Prevention also involves public health interventions separating infected from uninfected people.

For its part, treatment requires that health services address the needs of Covid-19 patients while at the same time protecting health service workers and non-Covid-19 patients from undiagnosed patients presenting for non-Covid conditions.

But for this to happen there has to be rapid turnaround of test results. In the absence of this, all patients awaiting results need to be treated as potentially Covid positive. This, in turn, requires staff to have full personal protective equipment when treating all patients. But public sector facilities aren’t able to reliably provide personal protective equipment.

Covid-19 patients also need expensive hospital-based care together with oxygen, ventilators (when oxygen proves insufficient on its own) as well as a variety of medications. Using private sector inpatient data from the Hospital Association of South Africa, the distribution is: general ward (64.2%), high care (15.7%) and intensive care units (20%).

The supplementary budget announced by the minister of finance makes provision for an additional R21.5bn for health to be split between the provinces, which will get most, and the national department of health. The problem is that, though money has been made available, there’s no associated strategy that sets out how it will be spent. This is a major omission that suggests the funds will not have any meaningful impact.

Missing strategies

The number of cases has been rising steadily in South Africa since around 22 April 2020. The lockdown was implemented on 27 March 2020 to stop the epidemic until such time as alternative prevention strategies could be put in place and to ready health services. Neither objective was achieved. Not only did the lockdown not stop new infections, as has been achieved elsewhere, but testing and tracing at scale was not implemented by the end of April as promised, and health services are in no position to cope with an uncontained outbreak.

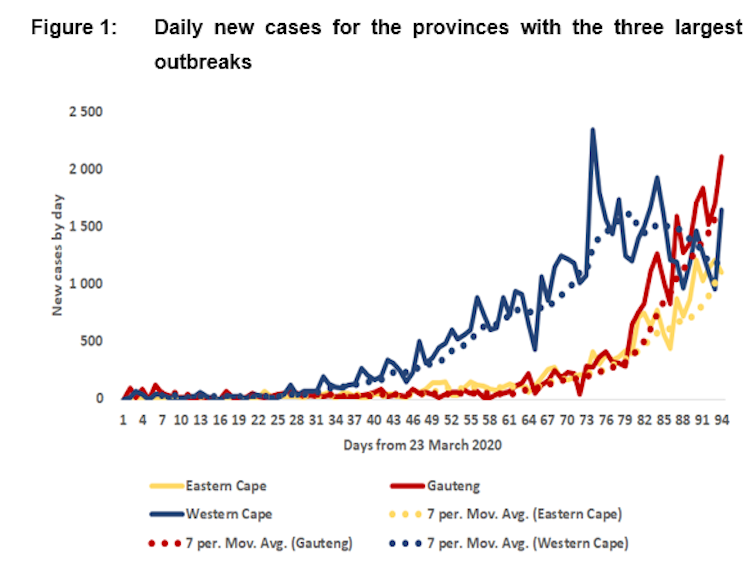

During April, May and early June 2020 the Western Cape experienced increasing new cases relative to all the other provinces. During the course of June the outbreak appears to have peaked due to interventions targeted at hotspots (Figure 1).

Over the same period the Eastern Cape and Gauteng provinces have seen a spike in new infections (Figure 1). Inpatient numbers and expected deaths have not yet caught up with these steep increases. But the impact on services is likely to rise steeply.

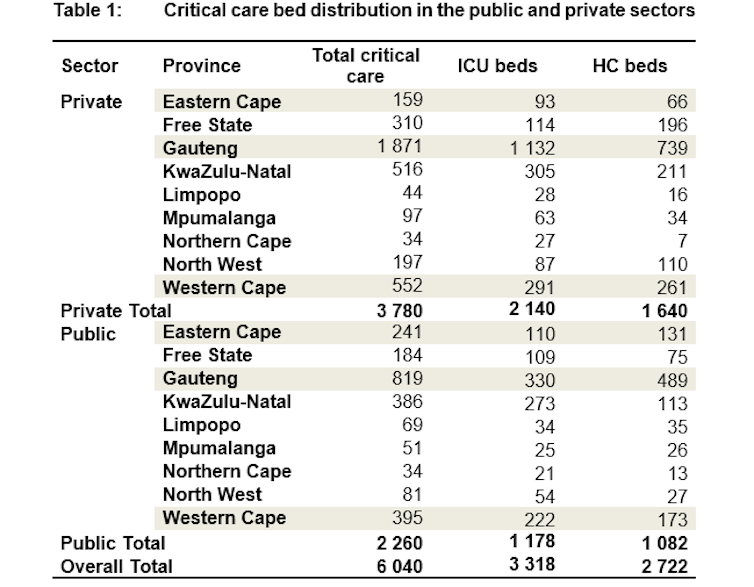

Gauteng is fairly well-resourced in critical care beds (2,690 with only 819 in the public sector), when both the public and private sectors are aggregated. But the Eastern Cape is far behind (400, with only 241 in the public sector) (Table 1).

Given what lies ahead, how will the supplementary budget help?

Of the additional R21.5bn made available for health, R16bn will be transferred to provinces as an adjustment to the provincial equitable share allocation (formula-based and allocated at the discretion of the province). The remaining R5.544bn is allocated to the National Department of Health.

The biggest problem is that these allocations are not connected to any strategy. The budget documents state broadly that the funds are meant to support testing, community health workers, expanding hospital capacity for critical care and field hospitals, PPE, oxygen, ventilators and new staff.

A number of immediate concerns therefore arise.

First, the R16bn is a general augmentation of provincial health budgets. It gives no consideration to differences in the provincial Covid-19 disease trajectory or likely impacts on services.

Second, it is unclear how testing and tracing infrastructure is to be expanded. For example, does it include funding university and private sector laboratories?

Third, no clarity is provided on how the R5.544bn is to be spent by national government.

What this means is that funding is likely to be allocated inefficiently. Some provinces won’t get what they need while others will waste allocations on less important functions. Because the funds aren’t earmarked, provinces can also choose not to allocate them for Covid-19 health interventions.

Another major gap is that the budget doesn’t offer any strategy or strategic targets when it comes to testing. Provincial governments will have to fund testing out of their existing budgets for the remainder of the year. This could, based on my own estimates, range from R3bn (15,000 tests per day) to R8bn (40,000 tests per day).

Provinces also need to fund quarantine sites and additional hospital beds. No strategy on either is outlined.

Overflow requirements for beds in the private sector are priced at R16,000 per day for critical care. Given that an overflow requirement introduces a demand-driven element into the budget process, significant contingent fiscal risks arise.

Again, however, no strategy is outlined.

South Africa only has critical care bed capacity for the remainder of the financial year of around 468,433 bed days (account has been taken of existing occupancy), of which 90,400 bed days (16.3%) are in the public sector. However, if the epidemic trajectory continues as at present, Covid-specific critical care bed need may be as high as 2.9 million bed days over the period July to December 2020.

As this would exceed both the financial and human resources of both the public and private systems, prevention strategies would need to be substantially more effective than at present.

It would therefore have made more sense to clarify the strategy. This would logically require flexibility in the budget process to enable prioritisation between prevention strategies and differential provincial treatment needs.

The increase in the equitable share allocation by R16 billion has, however, removed any flexibility for national government to shift funds to the highest strategic priorities by province. The remaining national allocations appear insufficient to fine tune prevention strategies or to augment provinces in greater relative need for hospital beds.

Now what?

The relative prioritisation of prevention over treatment for Covid-19 is neither explicit in government’s Covid-19 strategy documents, nor determinable from resource allocations in the supplementary budget. While this distinction may appear unimportant, disease prevention can only succeed if resourced at sufficient scale to avoid the catastrophic demand for critical care services for which no preparation will be sufficient.

Consistent with the handling of the pandemic to date, however, there is no evidence of a strategy. The supplementary budget for health is merely further evidence of this.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Source: The Conversation Africa

The Conversation Africa is an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community. Its aim is to promote better understanding of current affairs and complex issues, and allow for a better quality of public discourse and conversation.

Go to: https://theconversation.com/africa