We mapped green spaces in South Africa and found a legacy of apartheid

How much has actually changed?

The World Bank has found that economic inequality has increased since the arrival of South Africa’s democracy in 1994. The richest 10% of South Africans own 71% of the country’s wealth. In simpler terms, imagine a dinner party for 10 people where one person gets to eat 4 full chickens while the others only get one drumstick. The country is officially the world’s most unequal country. But financial inequality is just the tip of the iceberg.

Colonial powers dispossessed Africans of their land. Then the apartheid government enforced a racial hierarchy that systematically disadvantaged those who were classified as “Coloured”, “Indian/Asian” or “Black”. Coloured was used to refer to people of mixed European (White) and African (Black) or Asian ancestry. These where the racial categories assigned to South Africans under apartheid. In the country as a whole and in cities, people defined in this way were forced to live separately.

Since then, efforts towards land redistribution have been minuscule. In 2016, Black Africans, who make up 75% of the population of South Africa, owned only 29% of the land. The patchwork of racial segregation persists to this day.

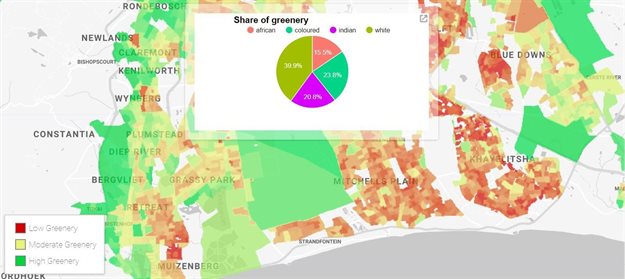

One aspect of this spatial segregation is often overlooked. It takes a bird’s eye view to fully appreciate it. Satellite images and drone footage are illuminating the full extent of South Africa’s “green apartheid” – the uneven distribution of city trees, greenery and parks across racial and income geographies.

We conducted a nation-wide study of all South African cities to quantify the extent to which green spaces are unequally distributed. Explore the results interactively here: green-apartheid.zsv.co.za.

Using publicly available satellite images in combination with the 2011 census data, we found that virtually all (96%) South African cities remain under a form of green apartheid. White citizens tend to live in areas with many more trees, greener vegetation, and easier access to public parks than areas with predominantly Black African, Indian, and Coloured residents. The same is true for high income relative to low income areas.

These findings are significant because they provide evidence for yet another form of spatial inequality that has not been adequately redressed since apartheid.

Public spaces neglected

This pattern isn’t only the result of the fact that White citizens are generally wealthier and able to maintain bigger and greener gardens around their homes. The inequality is as prevalent in public spaces.

For instance, when we examined how public parks are distributed over the country, we found that Black African residents have to walk, on average, 17 minutes to get to their closest park while White residents have to walk only seven minutes. Black Africans will also have to walk along streets with less and often no tree cover. This is perhaps exaggerated in areas designated as “locations” or “townships” for Indian, Coloured and Black citizens under apartheid.

By examining historical satellite images over South Africa we found that this green apartheid was evident in 1994, and very little has changed since then. In fact, urban wards with a strongly Black African majority are even more deprived of greenery than they were in 1994.

To some extent, this is understandable because government had to allocate scarce resources to socioeconomic priorities, including basic service delivery and rapid human settlement development.

While government has made headway with building grey infrastructure like houses and schools, green infrastructure like trees and parks has been severely neglected.

The importance of urban green

Some may criticise the push for conserving or promoting urban greenery as another manifestation of colonialism. Aren’t we enforcing western ideals of maintaining manicured gardens and green hedges? The same ideals that valued conservation of nature at the expense of indigenous peoples, or sacrifice economic development for environmentalism? These critiques may be oversimplifying the matter and ignoring the emerging “green economy”.

Economists and urban planners refer to vegetation and nature in cities as “natural assets”, or “green infrastructure” for a reason. Firstly, vegetation provides jobs. In just 12 towns across South Africa’s Eastern Cape province, the gardening sector (private and public) employs 17,429 people and pays R503m (over $30m) annually.

Secondly, urban greenery offers many benefits that are difficult to put a price tag on. Green spaces like parks and green belts have positive effects on physical fitness, mental health, social cohesion and spiritual wellness. City trees reduce extreme temperatures, mitigate flooding and clean the air of harmful pollutants. Even just looking at a tree can have psychological benefits.

Green justice

Correcting the spatial inequalities in urban green space is not a walk in the park. These inequalities also plague cities in many other countries, in the global North as well as the global South.

There is perhaps hope for South Africa with the enactment of the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act of 2013. The act aims to address past imbalances and provide for equitable access to green infrastructure. Yet governance structures have failed to implement greening programmes in the past due to lack of finance, poor cooperation and the view that green infrastructure is an optional luxury.

In the absence of government accountability, citizens resort to grassroots initiatives aimed at redistributive and environmental justice. For example, Reclaim The City is addressing the more obvious spatial inequalities in land and property distributions in Cape Town. Groups like Greenpop started with a more explicitly environmental focus to plant trees in marginalised communities.

To fully uproot green apartheid in South Africa will take time. Any instruments of economic development as well as redistributive justice would do well to include urban greening agendas to dismantle the racial, economic and green apartheid in South African cities.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Source: The Conversation Africa

The Conversation Africa is an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community. Its aim is to promote better understanding of current affairs and complex issues, and allow for a better quality of public discourse and conversation.

Go to: https://theconversation.com/africa