The future of shopping malls and what it means for property investors

This holds ramifications for the world’s shopping centres and malls as retailers re-evaluate their 'bricks and mortar' store strategies. Investors in commercial real estate funds, which often own retail premises, must understand the implications of these trends. As investors in global cities, we have been closely monitoring developments.

Which areas have been impacted most?

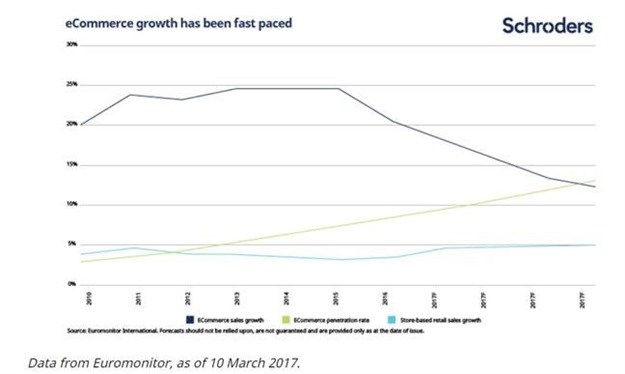

The impact so far has been most visible in the US. Weak sales figures have led to numerous store closures and layoffs. Perhaps the most important question is whether the US experience will be repeated in Europe. The charts below are based on data published by Euromonitor International and capture the growth of e-commerce.

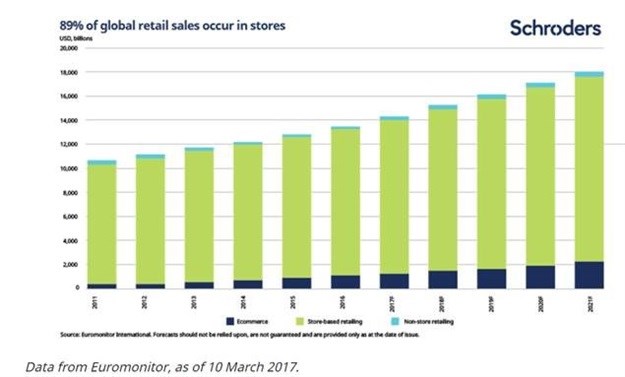

The vast majority of the world’s purchases – 89% of the total – are still made in a store. Online sales have been growing rapidly for the past decade, even if growth slowed last year.

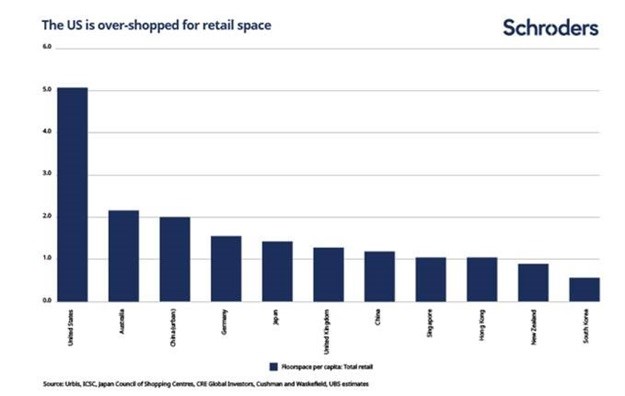

Some commentators have suggested the problems experienced by malls in the US will be replicated in Europe. The markets, however, are very different. Most importantly, America has a remarkable glut of shops. It has more than 5m2 of shop space per consumer, far higher than elsewhere.

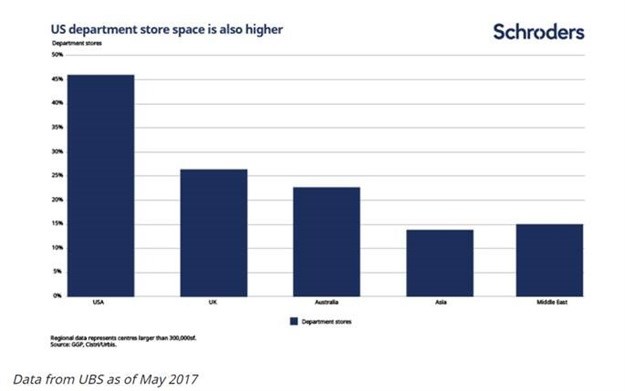

The situation in the US is further aggravated by the number of department stores. These outlets have felt the ill-winds of changing shopping behaviours most acutely. US malls are typically anchored by four department stores, a figure that is likely to fall to just two. Even iconic brands are struggling. Macy’s and Sears have already announced hundreds of store closures between them, mostly in malls. Analysts expect much more similar announcements within the industry.

Department store sales were strong in the 1990s but decline set in during the early 2000s. Between 2007 and 2012, sales fell by an average of 3.1% a year worsening to 3.7% in the years after 2012, according to US Census figures.

Is Europe next?

The march of Amazon and other e-retailers is unstoppable. Real estate investors can’t afford to be complacent about the implications. However, as outlined in the data above, there are mitigating factors in Europe. Malls on the continent are less likely to be anchored by department stores, with supermarkets, electronics and fashion brands used to pull in shoppers instead. In fact, the two largest European retail REITs, Klepierre and Unibail, only lease negligible amounts of space to department stores.

The geography of malls in Europe is also different. The planning is more restrictive so shopping centres tend to be nearer population centres rather than built further out in rural areas as is often the case in America. European shopping centres are often on infill sites in easy reach of large numbers of affluent shoppers. Westfield serves as an example with locations in densely populated and well-connected areas of east and west London.

The power of premium shopping centres to reinvent themselves should also be noted. Those that can lay on a great shopping experience, which often includes add-on activities and special events, will keep attracting high-end retailers. Most importantly, malls that remain popular with shoppers will attract retailers that are merging their online and physical store strategies.

An example of this can be found with one of the world’s most iconic brands. Apple uses its stores as showrooms, to allow customers to try before they buy. In France, 70% of Apple stores are now located in shopping centres with just 30% found on the High Street. Its push into flagship malls may be followed by other brands. Nine out of Apple’s 20 stores in France are owned by one real estate investment company, Unibail, which is focused on super-prime centres. Real estate investment companies (REIT), and the funds that back them could benefit.

It may also be that the closure of department stores for some centres will be manageable. In Singapore, department store closures have had little impact on malls, or at least those with the highest footfall. Even in the US Simon Group, the biggest mall operator that has seen its share price tumble in the past year, has seen some success in backfilling vacant department stores. Other groups with lower grade malls are having less success.

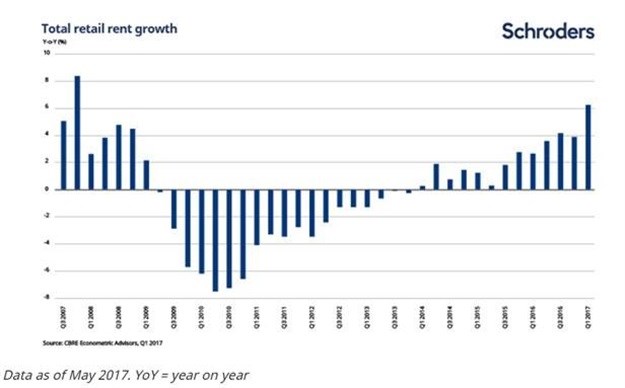

It should also not be forgotten that retail rents, which declined between 2009 and the end of 2013, are rising again. In the first quarter of 2017, rents increased at an annual rate of 6%, nearly double the rate of a year earlier.

The future

There are clear differences between the US and Europe but the broader trends within retail are unassailable. It is clear to us that few of today’s prime European malls will remain prime in 10 years’ time.

Malls near to large, affluent catchments of consumers will retain rental pricing power and occupancy. Some will become centres for leisure – places where consumers interact with brands. They will benefit as companies dedicate more of their marketing budgets to their stores. Some of these mega malls remain sensible investments.

Secondary malls with weak sales and declining footfall, often a symptom of below-peer demographics, will be marginalised, suffering declining rents and rising vacancies. The lesson from America is that much of Europe’s shop space is on borrowed time. The trend is clearly not the mall’s friend.