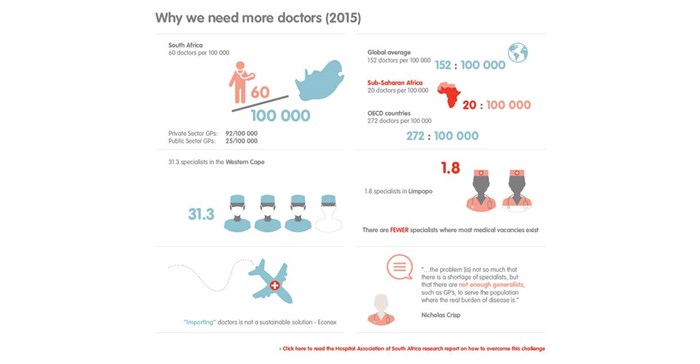

The world average of doctors to population stood at 152 per 100,000 in 2013. In South Africa it stood at a paltry 60 per 100,000. The reason are not unfamiliar in the South African context - large inequalities in the distribution of resources between the public and the private sector, as well as between rural and urban areas.

The Hospital Association of South Africa (HASA) – the body that represents the private hospital groups in the country – commissioned a Econex study to highlight this shortfall in light of the proposed National Health Insurance (NHI) plan, as well to plead the case for private medical schools.

“Given the envisioned re-engineering of primary healthcare in South Africa, the NHI will require greater numbers of clinical and non-clinical professionals with different skills and competencies. Minister of health, Aaron Motsoaledi, has stated that he plans to triple the number of medical graduates to at least 3,600 doctors per year in preparation of implementing the NHI,” the report says.

Emigration and foreign doctors

Training capacity will have to be increased substantially in order to achieve this goal. The emigration of healthcare professionals and restrictions on foreign doctors working in South Africa contribute to the doctor shortage.

The most significant factor that limits the supply of doctors from meeting demand, however, is the number of doctors being trained at the moment at the eight faculties of medicine at South Africa’s public universities. These medical schools carry the full responsibility for training doctors, but cannot deliver enough doctors to respond to the country’s demand and large disease burden.

“The prohibition on establishing private medical colleges in South Africa limits the private sector’s ability to help lift this burden, and leaves training in the public sector constrained by limited funding and resources,” the report says.

Training in China and Cuba

National or provincial governments, universities and the private sector have tried different approaches to address the lack of training capacity for healthcare professionals in South Africa. One such policy is to send students to countries like Cuba and China for medical training.

“We argue that the long-term effectiveness of such policies needs to be weighed against counterfactual scenarios and the quality and suitability of medical education received.”

“Training doctors abroad is at best a temporary solution to doctor shortages in South Africa. Instead, partnerships between universities and provincial governments, as well as (limited) partnerships between universities and the private sector have been proven to help lift the burden, albeit only marginally, and should be further encouraged. The structural shortage of doctor training capacity will best be solved through a combination of initiatives.”

Initiatives of other developing countries

The rise of private medical schools in India, for example, has retained medical students who might otherwise have studied abroad. Brazil relies on both public and private medical schools to provide training, and uses both of these platforms to provide healthcare services to communities while students are in training.

Indeed, research shows that private medical schools are common internationally and as a rule provide high quality education. Other important lessons can be drawn from African countries like Malawi, which has increased its training capacity with the help of international volunteer doctors. Zambia’s experience illustrates that exposure to rural areas during training needs to be complemented by adequate mentoring in order to provide healthcare practitioners in these areas with the necessary skills.

Greater participation by the private sector can thus play an important role in the provision of medical education. This study considers two possible avenues of participation:

- allowing the establishment and accreditation of private medical colleges, and

- encouraging greater participation by private hospitals and specialists in the clinical training of undergraduate students studying at South Africa’s public universities.

South African landscape

Econex says that rather than posing a threat to the public sector, the private sector can strengthen South Africa’s medical workforce by helping government achieve many of its stated healthcare objectives.

In the first instance, the accreditation of private medical colleges can allow a greater number of doctors to be trained at minimal cost to the public purse.

However, the perceived inequality in the distribution of resources between the private and public healthcare sectors creates the concern that private medical colleges will exacerbate current inequalities and give rise to elitist private training facilities. This history of antagonism in South Africa’s healthcare suggests that while private medical colleges provide a structural long-term solution, it will not be easy to implement in the short term.

In the second instance, the role that greater participation by private hospitals can play in doctor training. There are already examples where the private health sector and public universities have collaborated effectively to lessen the training burden on public medical schools.

Local initiatives

An initiative between Mediclinic South Africa (MCSA) and Stellenbosch University (US), where internal medicine students in mid-rotation complete a portion of their clinical training at a MCSA hospital, suggests that the private sector can contribute to the training capacity of public universities. It provides an easy and cost effective way of increasing the number of doctors in South Africa, without skewing the distribution of healthcare resources.

Netcare and Life Healthcare also contribute to lifting the training burden of the public sector through making funding and scholarships available for specialist and sub-specialist training.

Greater involvement by the private sector in medical training should therefore be investigated and encouraged as a matter of priority, especially in light of the demand that the NHI will create for more doctors.

The private sector can also be used to help address the need for more healthcare resources in rural areas, where South Africa’s doctor shortage is especially acute. More doctors will be available for community service and internships in rural areas if larger numbers of students are trained. Strategic agreements between (public or private) universities and rural clinics could also be tailored to increase the propensity of medical students to practise in these areas.