The third session of the UCT Unilever Institute of Strategic Marketing's Youth Report 2018 release was presented by Martin Neethling, director of groceries at Pioneer Foods, and was all about the 18- to 24-year-old market, the changing definition of teenagers and the game-changers in this regard.

Slide 161 of Youth Report (2018). UCT Unilever Institute of Strategic Marketing & Instant Grass International.

Neethling spoke of the state of youth today and how we can best describe that reality.

He started by asking attendees to estimate how many 18- to 24-year-olds live in households earning more than R30k a month? The answer was just 292,000. That’s from the 7.4 million 18- to 24-year-olds living in South Africa – 14% of the population.

Neethling said this figure shows that the extent of privilege of any sort has shrunk.

No job for money, no money for job search

This cohort was born between 1994 and 2000, so is on the border of two generational cohorts. Most grew up facing some level of poverty or disadvantage, with many challenges still ahead.

Speaking of game-changers and what’s likely to change the outcome for this cohort, Neethling listed them as the seemingly obvious education, then the not-so-obvious ‘micro-privileges’ – even in the same suburbs and schools.

This everything from the presence of books in the home, with 65% of respondents having less than 10 books in the house as they grow up; to having a room or even corner to call your own; or a teacher living at the home. Those little advantages from the early years magnify over time.

Third, is the proximity to opportunity, both literally and figuratively. If you don’t have a job, how do you earn money for transport, to go out looking for a job? You get stuck. You become part of generation jobless.

It’s an inequality of outcomes between vulnerable and resourced youth.

But what has truly changed over the years?

Slide 97 of Youth Report (2018). UCT Unilever Institute of Strategic Marketing & Instant Grass International.

The first game-changer is the actual transition to adulthood. Neethling said that the word ‘teenager’ was first used in the 1920s, and was seen as a time of overlap between childhood and the responsibilities of adulthood. It’s worth thinking ‘when are you old enough’, as there are surprising differences across the globe.

Changing rites of passage

For example, Neethling said you can get married as a male at 22 in China, yet in the US, you can buy an AR-15 rifle at the age of 18 and can watch Fifty Shades of Grey if you’re 12-years-old in France.

Looking local, the age of consent is 16, you can earn your helicopter pilot license at age 17 and by 18 you’re able to vote, drink, drive and join the army.

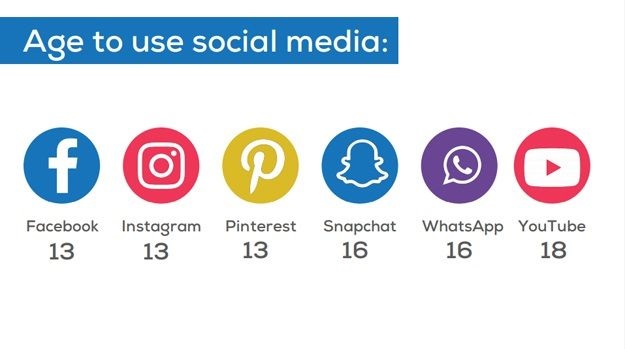

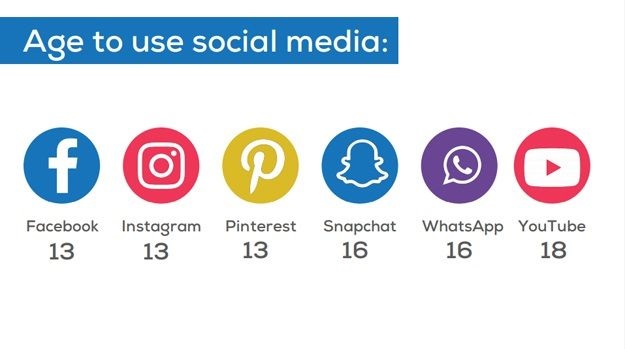

That said, you may be in for a surprise when it comes to the age of consent for using the various social media platforms:

Slide 104 of Youth Report (2018). UCT Unilever Institute of Strategic Marketing & Instant Grass International.

And yet, in 2018, there’s a sense of delayed adulthood, where the youth live at home for longer, study longer, take longer to find a job, and have extended dependence on family.

This results in being seen as an adult but not quite, so the ‘18 to 24’ cohort sees either their forced 'waithood' or ‘explorehood’ of choice, as a time to take little bites at adulthood through ‘kidulting’ or ‘adulting’ for bits of a time – their parents are also grappling to come to terms with this, treating young adults as children to avoid confronting the reality that they are middle-aged.”

The second big change is that of exposure, which is not unique to South African youth. The youth are more exposed and expose themselves to more, and the omnipresence of the cell phone means we see things we can’t unsee and do things we can’t really undo.

Today’s access to content is almost without boundaries. Neethling spoke of the impact of that on how young people enter the world. In the process of doing so, they also expose themselves to the world, so it’s a two-way looking glass that has far-reaching consequences. Trust issues and social media addiction

According to results from the UCT Unilever Institute of Strategic Marketing’s primary research on an unweighted sample of 815 youth aged 18 to 24, 93% of respondents have their own social media account and they spend hours each day keeping up with others and curating their own image in the big wide world – depending on access to data, of course.

Teenagers also use those profiles across different social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat in different ways, as they are each fit for purpose and often used in combination.

Facebook is for lifecasting, and a distraction throughout the day; Twitter is for catching news as it happens – for hating and for hustling; Instagram is for inspiration; and Snapchat is for event teasers and quick bursts of distraction while studying.

On the manifestations of this, Neethling said the first is the slightly rhetorical question of

who to trust, when we are swamped with so much information – and that’s not even touching on fake news.

The easy answer is that we trust our friends, but many of those we call ‘friends’ are just online acquaintances we’ve never met in real life.

The second manifestation is that this is completely addictive and as a result, also indispensable.

Third, is the idea of a broken trend curve. Typically, the curve shows early adopters as the richly resourced, but with the exposure dynamic for this cohort, there’s been a democratisation of trends.

Neethling said it’s a trickle-up effect, with many responses emerging from the townships, like the birth of DStv Compact, from lower-income consumers refusing to pay premiums, or the gwara-gwara dance from Soweto, as seen in Childish Gambino’s This is America – Neethling briefly demonstrated.

Watch for more coverage of the UCT Unilever Institute of Strategic Marketing’s Youth Report 2018, and follow them on Twitter for the latest updates.