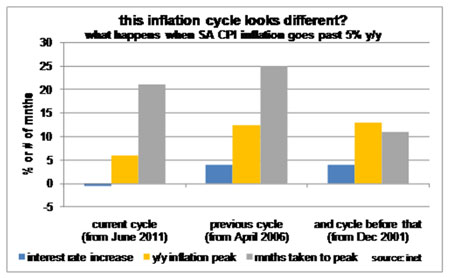

The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) expects CPI inflation to average 6.3% in the third quarter of 2013, before returning to the targeted 3% to 6% band in the fourth quarter. In the previous two inflation cycles (see chart below), the SARB started to increase interest rates when inflation exceeded 5%.

Typically, despite interest rate increases, inflation would peak significantly higher than 6%. This time around, inflation rates have remained remarkably restrained, despite CPI inflation increasing above 5% in June 2011, and the SARB actually surprising the market with an additional interest rate cut.

In this inflation cycle the SARB has not felt it necessary to respond to rising inflation with increased interest rates, as neither the over-indebted consumer nor credit-constrained business has been in a position to respond aggressively to record low interest rates.

In hindsight, the Reserve Bank may until now have been right to rely on excess capacity in the economy and deflationary forces brought about by both global and local debt deleveraging to keep inflation under control. However, it risks undermining its inflation-fighting credentials by not responding to increased inflation with increased interest rates, particularly since it reflected at its March Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting that the risks to inflation were on the upside.

It is worth recalling the battle central bankers had to fight (with aggressive increases in short-term interest rates) for monetary policy to become a credible tool for fighting inflation, after the debilitating stagflation of the 1970s.Once inflation expectations are entrenched, strong medicine (with its negative implication for asset class returns) is required to revise them downwards.

What are the implications?

What implications does this challenging macroeconomic environment have for investment strategies that aim to deliver inflation-beating returns? Firstly, the risk of a policy error (i.e. that the SARB leaves interest rates on hold for too long, or mistakenly cuts rates again) cannot be discounted and the prospect of a return to a 1970s' scenario of stagflation (weak economic growth and high inflation) is not out of the question. We should, therefore, be reluctant to rely too heavily on politicians both locally and abroad to get the policy mix right in appropriately managing inflation expectations.

Even if policy makers do get their interest rate policy correct and prevent inflation from getting out of control while still encouraging economic growth, the "search for yield" theme has resulted in fixed interest and certain select equities being priced to perfection. It is, therefore, difficult to see how investors can earn exceptional returns from these asset classes without employing an active management strategy (i.e. investors need to find managers that can significantly outperform their benchmarks).

In such an environment, increased emphasis is required on asset managers themselves (as opposed to the asset classes they invest in) to deliver exceptional investment returns.