How we can "bank" water underground for use later on

Since groundwater was developed as a science 150 years ago by Henry Darcy, several ideas using engineering and technology have cropped up on how best to manage it. Aquifers, which are groundwater reservoirs, have been used for centuries as a water source for drinking and agricultural purposes.

One idea is known as managed aquifer recharge. Here, groundwater is recharged in a controlled way into the aquifer. This allows water to be “banked” – stored underground – so that it can be used later.

Banking water minimises the impact of evaporation and means that water can also be recycled from various sources, instead of being wasted. This recycled water could stem from stormwater or even wastewater treatment plants and then be put back into the aquifer.

The fundamental idea behind better groundwater management emerged from the Middle East during the 1st millennium BC, where they are known as Qanat systems. These were hand dug tunnel and outlet well systems, which basically lead groundwater from one point to another for abstraction.

Today, various forms of managed aquifer recharge projects can be seen all over the world. In the US, they’ve increased from three well-fields in 1985 to approximately 72 in 2005 and many are in various stages of development.

In Africa multiple projects are being developed in several countries including Namibia and South Africa.

South Africa’s Atlantis dune field, which is comprised of infiltration ponds, has been operating for over 40 years. It uses recharge basins that are larger than 50 hectares in size. The aquifer produces about four million cubic metres of water each year. This supplies the town of Atlantis with the majority of its water.

Recharging aquifers

Groundwater recharge, defined as the addition of water to the aquifer once it has reached the water table, can happen in several ways:

• Water flows downward, because of gravity, and reaches the water table

• Water flows underground from one aquifer to another

• Groundwater abstraction leads to pumping and changes in flow directions below the surface and so nearby surface water bodies release water into the connected aquifers

• Artificial recharge. This can be done by means of borehole injection, via a well, or man-made infiltration ponds, which are permeable depressions allowing water to infiltrate into the aquifer.

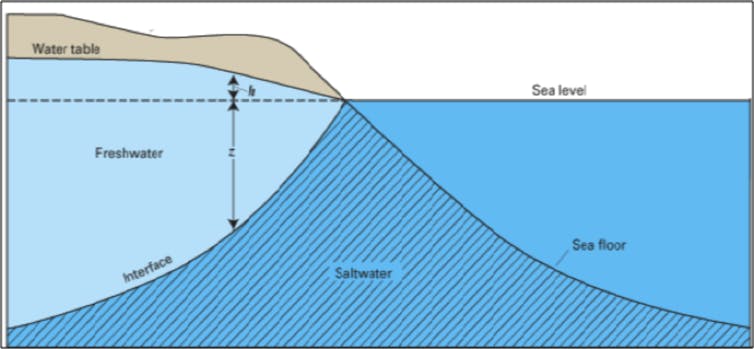

This last means of recharge is managed aquifer recharge, where water is "banked" and can be used later on. It is also used in coastal aquifers, to prevent too much seawater from getting in by injecting fresh water into groundwater reservoirs. This minimises the impact which salt water has on the aquifer and extends the life of the groundwater reservoir.

There are many ways and models for managed aquifer recharge. These include:

• Aquifer storage and recovery: water is injected into and extracted from the same borehole

• Aquifer storage, transfer and recovery: water is injected into and extracted from different boreholes in the groundwater reservoir.

• Infiltration basin: when a large depression, made in a similar manner to a dam, allows surface water to infiltrate the soil and recharge the groundwater

• Bank filtration: wells located alongside surface water facilities are pumped to induce recharge

These are chosen based on the geology of the area or on how much water is needed.

Successful banking

The process isn’t a magic bullet. It does have some issues. One of the major problems is that wells could get clogged up by organisms that grow due to the large amount of oxygen that accompanies water injection. But this can be solved by using heated water or chemical injections to kill off the microbes.

For projects to be successful there also needs to be a reliable source of water, good engineering expertise and proper environmental and legal regulations.

There also needs to be a proper assessment on whether an aquifer can just be better managed – a simple, yet effective, solution that can cut costs and increase the longevity of an aquifer rather than implementing a managed aquifer recharge scheme.

Banking water is not simple and needs meticulous planning and execution. But, in places where it is needed, the opportunities it presents allow us to minimise the impact which evaporation has on our water supplies and this means more water for more people.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source: The Conversation Africa

The Conversation Africa is an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community. Its aim is to promote better understanding of current affairs and complex issues, and allow for a better quality of public discourse and conversation.

Go to: https://theconversation.com/africa