There is an old joke they tell in Democratic Republic of Congo: Mobutu Sese Seko, the strongman who ruled the country with an iron fist for three decades, receives a phone call from a fellow African leader. He is under rebel attack and needs advice.

Road transport is an important ingredient for economic growth in Africa and completing and maintaining the Trans Africa Highway will go a long way toward helping Africa build. (Image: Göran Höglund)

"Did they come by sea?" Mobutu asks.

"No," the younger ruler replies.

"Did they come by air?" Mobutu asks.

"No, they came by road," his protégé answers.

"Tsk tsk, my son, I always told you," Mobutu says. "Never build roads."

Transport infrastructure matters. It costs an African farmer about $2 a ton per kilometre to move produce to market. This cost - it's about half that in North and South America - has restricted farming to within six hours of a major city. Today, according to the World Bank, just 34% of Africa's rural population lives within two kilometres of an all-season road. This lack of access to infrastructure has restricted trade between African countries to just 12% of total trade; in comparison, trade between neighbours in North America - Mexico, the US and Canada - accounts for 40% of all their trade.

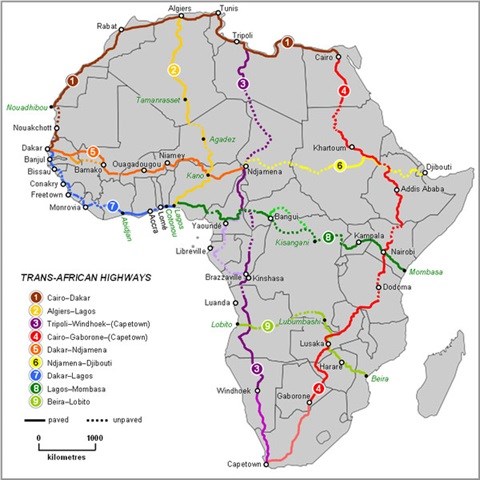

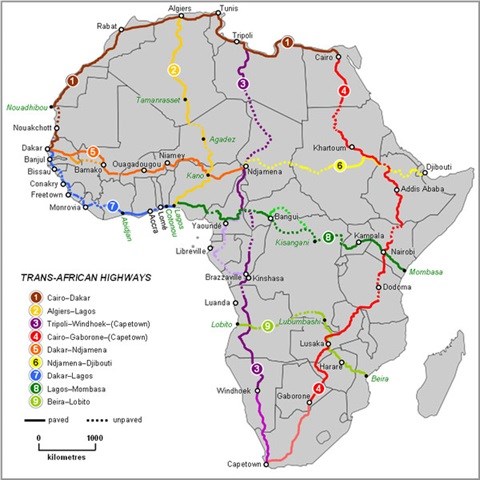

The African Union's Intergovernmental Agreement on the Trans-African Highway Network sets minimum standards for development and maintenance of 57,233 kilometres of road that make up the Trans-Africa Highway today. Designed to connect capitals to centres of production, and connect Africa, it is hoped a well-maintained and fully realised highway will integrate economies and improve social cohesion between African communities.

The Trans-Africa Highway was meant to increase trade through built and maintained infrastructure and more harmonious customs procedures. A fully developed, continent-wide road system would aid African food security and lower the cost of feeding a family. Without it, in Africa it costs between 50% and 175% more to transport goods from the site of production than anywhere else in the world.

As African economic growth - and the resulting improvements in living standards - has outstripped developed countries, the shortage of infrastructure threatens to put a brake on development. As originally imagined, the Trans-Africa Highway was an impressive web of freeways that would link ports to cities to the hinterlands. It would carry billions of dollars of goods to markets and build self-sufficient continental economies.

But Africa's road network lags behind the global average of 7.6 kilometres per 1,000 people. It is anticipated that the harmonisation agreement and other programmes - such as Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (Pida) run by agencies like New Partnership for Africa's Development (Nepad) - will help increase the density from the present 3.6 kilometres per 1,000 people.

When foreign companies calculate the price of doing business on the continent, they look at figures such as the cost of transportation, and decide to go somewhere else. And transport delays caused by infrastructure limitations cut productivity in Africa by as much as 40%.

Improved roads in north and west Africa, and large-scale road building programmes in the Southern African Development Community and East African Community have gone a long way towards connecting and integrating Africa. The largest challenge remains in central Africa, where difficult geography and a lack of road infrastructure have made improvements challenging.

The biggest challenge to the completion of the highway is the dicersity of terrain, from deserts in the north to dense vegetation in central Africa. (Image: stopmangohome/Flickr)

Now, an $8-billion investment through the African Development Bank is driving the goal of a fully connected continent. This investment was made easier by a philosophical change among governments. Africa has come to realise that viable transport infrastructure is connected to the economic, technological and social renaissance of Africa. As Nepad's Adama Deen explained to a planning conference in 2013, "every country and every region has had its own master plan and priorities, now we can all come together as Africa to have one priority for the continent. By 2030, we will have developed a completely holistic African infrastructure system. If we fail, integration in Africa is impossible."

Africa's economy is evolving but agriculture, mining and tourism remain the mainstays and they are all dependent on crumbling roads. Economist Jeffrey Sachs has argued that developmental aid to Africa would be better spent on building highways suited to carrying truck cargo than on almost anything else.

In 1969, the Japanese government began building a four-lane highway to link Mombasa in Kenya to Lagos, Nigeria. At 7,080km, it was longer than the cross-continental highway linking Boston on the American Atlantic coast to Seattle on the Pacific, and would increase trade among six African nations.

But after Idi Amin took control of Uganda and threatened his neighbours, Kenya closed its end of the highway. Today, the east-west Trans-Africa Highway turns into a muddy footpath in the jungles of eastern Congo. "No one would ever have 100 million people in the rich world along a broken down, two-lane, undivided road as we do here," Sachs says.

Dreamed up more than 40 years ago by a UN committee and still being developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (Uneca), the African Development Bank and the African Union, the Trans-Africa Highway is a network of envisioned highways linking Africa from north to south and east to west. As Africa threw off the shackles of colonialism, Uneca's ambitious plan was to link Tripoli to Windhoek, Lobito in Angola to Beira in Mozambique. Another planned highway would link Khartoum to Gaborone. None of Uneca's original plans included routes into South Africa, at the time a pariah state.

Like Cecil John Rhodes' colonial dream of a path of red from Cape Town to Cairo, the Trans-Africa Highway network would make it easier to cover the vastness of Africa, and open the continent to internal and international trade. Spread across nine highways, it is an arterial network of tar, steel and ferries that, if ever completed, will comprise more than 56,000 kilometres of maintained corridors that will allow African farmers and miners to get their product to markets or to ports.

For the dreamers who imagined it and the Africans building it, the highway is designed to alleviate the poverty affecting large parts of the continent. By linking every African country it was hoped that the continent will become an integrated bloc, but four decades later that aim remains unfulfilled and construction on large sections stalled. As it stands, there are 10,400 kilometres of rail and 7,000 kilometres of the road corridor missing, and it will cost $32-billion to complete these links.

The highway consists of 9 different corridors that are designed to give every African country access to markets and ports(Image: UNECA)Read more: http://www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com/economy/3956-stalled-on-the-trans-africa-highway#ixzz38wUEjHgZ

The International Committee of the Red Cross's distribution hub for eastern Africa is just off the Mombasa highway in Nairobi. It costs the aid organisation $2.88 per 1.6 kilometres to ship aid to the most desperately in-need communities. "The roads are in a desperate state and they are not getting any better," explains Bent Korsgaard, Red Cross logistics director for the region.

African governments have had to balance the use of scarce resources between immediate needs and the maintenance of infrastructure. Roads have fallen down the list of priorities. Yet in the last decade, African governments, the African Union and the African Development Bank have changed their view. Roads - and other linked transport infrastructure - have become a priority. Infrastructure projects are now seen as the best way to improve Africa's trade with itself and the rest of the world.

At present, 40% of Africa's population lives with two kilometres of a tarred, all-weather road; doubling that access would cost about $32-billion. But spending the money would improve economies and improve food security for Africa's one billion people. Some governments have begun to prioritise rural road investment based on the agricultural value of land. Instead of investing immediately in building the 1.5 million kilometres of highway needed, an immediate improvement in prospects can be gained by building a network of 600 000 kilometres in rural agricultural areas.

Maintaining existing roads is the challenge for governments. In Africa 80% of paved roads remain in fair condition, and 85% of rural feeder roads are in a poor condition. (Image: Jbdodane/Flickr)

Since its inception in 2001, the Association of Southern African Roads Agencies (Asanra) has been responsible for planning, maintaining and developing road networks in the Southern African Development Community. Group programme officer Snowden M'madi explains: "Road transport is an important ingredient for economic growth, and this will be achieved in Africa through the Trans-Africa Highway."

For South Africans, especially residents of Gauteng, there is a stretch of the highway that has become a burr in their shoe. Ultimately, it will be a part of a 560km long stretch of the Trans-Africa Highway, but for now the tolled road between Johannesburg and Pretoria has become a source of friction between motorists - who feel they are overpaying for the road - and the South African National Roads Agency (Sanral), which views it as a vital economic artery.

It is one of 18 integrated projects - to improve infrastructure and water delivery - identified by the national government that is hoped will change the economic landscape of not just Gauteng but the whole country. Improved service delivery is also a major benefit that improved transport links will bring to South Africans.

Sanral's Nazir Ali pointed out at a CSIR conference as far back as 2012 that the government saw it as important to maintain and improve road infrastructure to unlock the economic power lying dormant in South Africa. "There is no country in the world where [the] government is not involved in any developmental activities. Allowing these assets to deteriorate would be a cost our economy, as well as cost us as individuals."