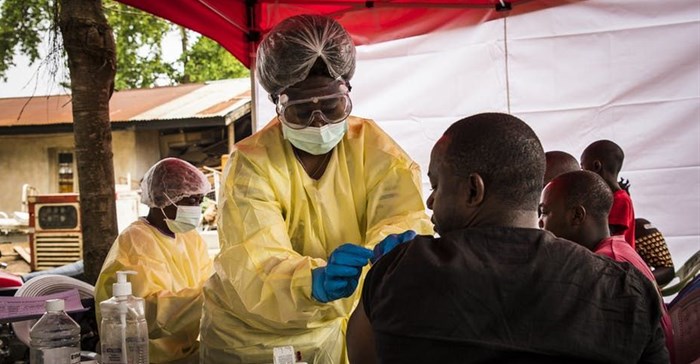

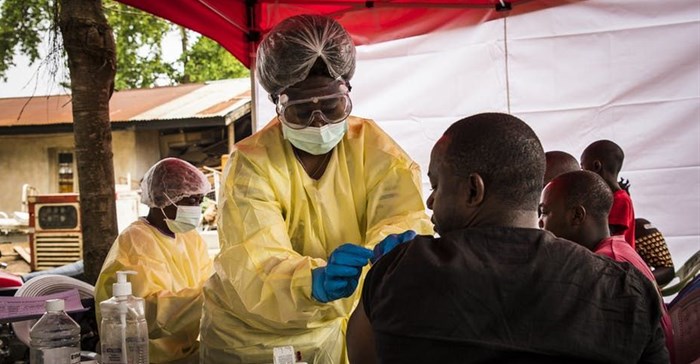

Health officer on the front-line in the DRC. Flickr

The emergency committee from the WHO – which is responsible for taking this decision – has met four times since the outbreak was declared in the DRC’s North Kivu region on 1 August 2018. During the last meeting in June the committee decided that the outbreak didn’t constitute a public health emergency of international concern.

A month later the committee changed its mind. Its reasons for doing so were that the number of cases had increased from 2071 to 2522. Even though the mortality rate had remained at 67%, three new cases were detected in Uganda. In addition, a case of Ebola was diagnosed in Goma, a city of almost 2 million that is a busy entry point for the DRC. The town sits on the Rwandan border.

The expected impact of the decision is that more funding will be raised for the response teams in the field as international support is stepped up. It will also give the DRC’s Ministry of Health more flexibility to ensure response teams reach even the remotest areas. More means are needed to ensure that teams are able to engage communities. Part of this is ensuring they have the logistics to access them, especially in the most remote places.

The decision is significant and should have a critical affect on the response. It will provide a second breath to address the new phase of the outbreak, hopefully ensuring that it is ended.

But the decision is not a silver bullet. The outbreak of a deadly disease within a conflict zone – and now in a major city – cannot be solved with a technical solution, such as more funding.

What’s working, what’s not

The Ebola response have not been enough to stop the spread of the outbreak. This is despite major efforts by the tireless Ebola response teams, community engagement, surveillance, vaccination and communication.

The number of cases and deaths have not declined. This suggests that people are still avoiding going to Ebola treatment centres to get care. This is despite the fact that new therapeutics are now being made available through a randomised clinical trial.

More than 100,000 people have been vaccinated. The vaccine hasn’t stopped the spread of the disease, although it has contributed to controlling it. The introduction of a second vaccine through a clinical trial would support the response, especially in the neighbouring regions of North Kivu, where no cases have been reported.

The other factor holding back efforts to eliminate the outbreak has been the increasing number of attacks on personnel in the area. Dr Richard Mouzoko, an epidemiologist working for the WHO, was killed in April and clinics have been torched. The attacks highlight the complexity of responding to the already complicated outbreak in a conflict zone.

The violence is also getting in the way of engaging with communities, a major part of any Ebola response.

The DRC has also been facing challenges in getting the funds it needs to manage the response efficiently.

The Public Health Emergency of International Concern announcement is a call to the international community for action. But extra funds won’t be enough. the issue of unrest in North Kivu needs to be solved as it remains one of the major catalysts of this outbreak. Solving the outbreak requires a peaceful environment, wherein the community trusts the Ebola response team, and therefore, increase its engagement. Without a higher community awareness and engagement, it is difficult to see the end of Ebola outbreak in the DRC.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.