How machine learning is helping us fine-tune climate models to reach unprecedented detail

With machine learning, we can use our abundance of historical climate data and observations to improve predictions of Earth’s future climate. And these predictions will have a major role in lessening our climate impact in the years ahead.

What is machine learning?

Machine learning is a branch of artificial intelligence. While it has become something of a buzzword, it is essentially a process of extracting patterns from data.

Machine learning algorithms use available data sets to develop a model. This model can then make predictions based on new data that were not part of the original data set. Going back to our climate problem, there are two main approaches by which machine learning can help us further our understanding of climate - observations and modelling.

In recent years, the amount of available data from observation and climate models has grown exponentially. It’s impossible for humans to go through it all. Fortunately, machines can do that for us.

Observations from space

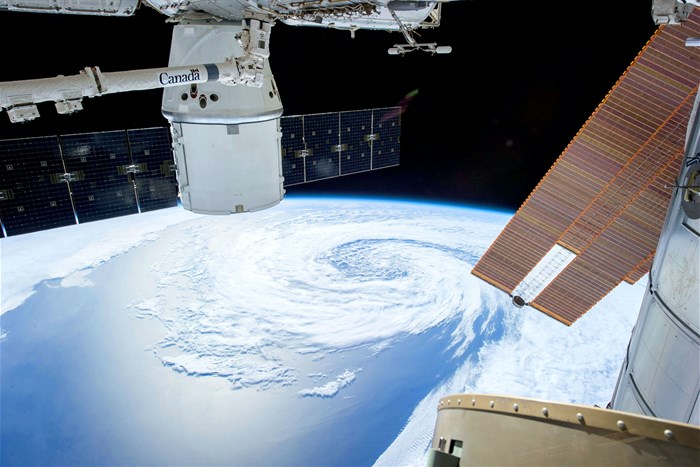

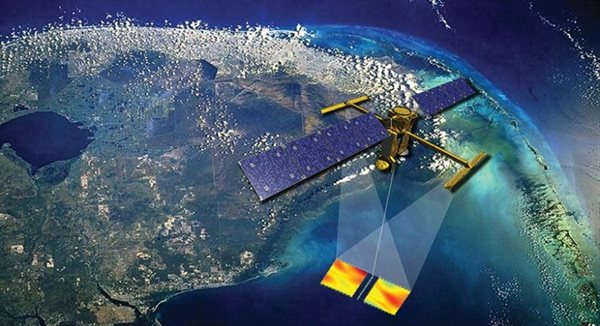

Satellites are continuously monitoring the ocean’s surface, giving scientists useful insight into how ocean flows are changing.

Nasa’s Surface Water and Ocean Topography (Swot) satellite mission, scheduled to launch late next year, aims to observe the ocean surface in unprecedented detail compared with current satellites.

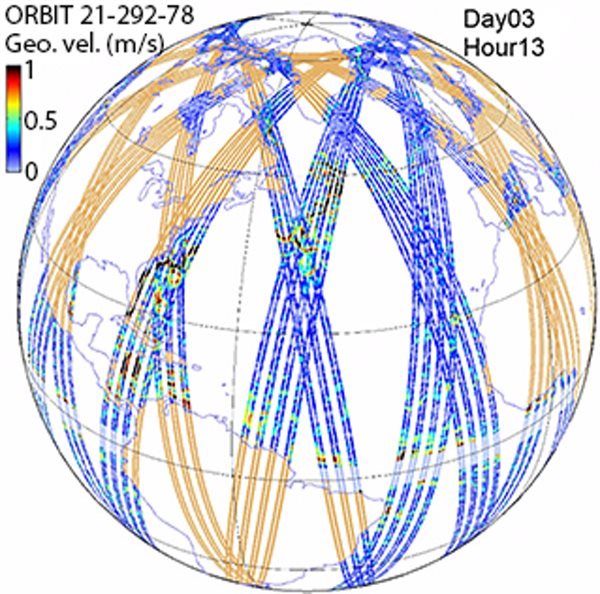

But a satellite can’t observe the entire ocean at once. It can only see the portion of ocean beneath it. And the Swot satellite will need 21 days to go over every point around the globe.

Is there a way to fill in the missing data, so we can have a complete global picture of the ocean’s surface at any given moment?

This is where machine learning comes in. Machine learning algorithms can use data retrieved by the Swot satellite to predict the missing data between each Swot revolution.

Obstacles in climate modelling

Observations inform us of the present. However, to predict future climate we must rely on comprehensive climate models.

The latest IPCC climate report was informed by climate projections from various research groups across the world. These researchers ran a multitude of climate models representing different emissions scenarios that yielded projections hundreds of years into the future.

To model the climate, computers overlay a computational grid on the oceans, atmosphere and land. Then, by starting with the climate of today, they can solve the equations of fluid and heat motion within each box of this grid to model how the climate will evolve in the future.

The size of each box in the grid is what we call the “resolution” of the model. The smaller the box’s size is, the finer the flow details the model can capture. But running climate models that project forward hundreds of years brings even the most powerful supercomputers to their knees.

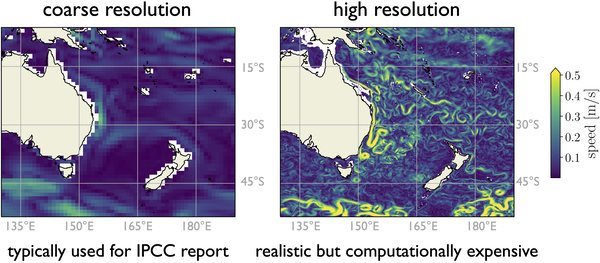

Thus, we’re currently forced to run these models at a coarse resolution. In fact, it’s sometimes so coarse that the flow looks nothing like real life. For example, ocean models used for climate projections typically look like the one on the left below. But in reality, ocean flow looks much more like the image on the right.

Unfortunately, we currently don’t have the computational power needed to run high-resolution and realistic climate models for climate projections. Climate scientists are trying to find ways to incorporate the effects of the fine, small-scale turbulent motions in the above-right image into the coarse-resolution climate model on the left.

If we can do this, we can generate climate projections that are more accurate, yet still computationally feasible. This is what we refer to as “parameterisation” - the holy grail of climate modelling.

Simply, this is when we can achieve a model that doesn’t necessarily include all the smaller-scale complex flow features (which require huge amounts of processing power), but which can still integrate their effects into the overall model in a simpler and cheaper way.

A clearer picture

Some parameterisations already exist in coarse-resolution models but often don’t do a good job integrating the smaller-scale flow features in an effective way. Machine learning algorithms can use output from realistic, high-resolution climate models (like the one on the right above) to develop far more accurate parameterisations.

As our computational capacity grows, along with our climate data, we’ll be able to engage increasingly sophisticated machine learning algorithms to sift through this information and deliver improved climate models and projections.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Source: The Conversation Africa

The Conversation Africa is an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community. Its aim is to promote better understanding of current affairs and complex issues, and allow for a better quality of public discourse and conversation.

Go to: https://theconversation.com/africa