Feeding cities in the 21st century: Why urban-fringe farming is vital for food resilience

When you pick up supplies at your local supermarket for tonight’s dinner, the produce will likely have come from many parts of Australia and from distant parts of the world. But some of the fresh produce may also have come from one of the highly productive foodbowls on the fringes of Australia’s state capitals.

The role that city fringe farmers play in feeding cities is sometimes overlooked in an era of sophisticated supply chains that enable food to be sourced from all over the world. But city food bowls make a significant contribution to Australia’s fresh food supplies, and cities can do more to support them.

Why being close to cities makes sense

Many cities now recognise the need to strengthen relationships with local farmers as a way to increase the resilience of their food supplies to climate change and make efficient use of scarce natural resources.

Retaining food production close to urban areas can reduce food shortages if transport routes into the city are cut off (for example, by a major storm or flood). Recycled water from city water treatment plants can also be used to grow food during a drought, and food waste can be processed into organic fertilisers for use on nearby farms.

Read more:

To feed growing cities we need to stop urban sprawl eating up our food supply

Strengthening links between cities and farms on the fringe can improve farmer livelihoods and grow the local economy.

Farmers on the city fringe are caught in a tight “cost price squeeze” with very high land prices (and rates) and low farm-gate prices. Many are small-scale farmers who find it difficult to compete through economies of scale. But there are also advantages to being close to the city, such as the proximity to city markets and access to recycled water.

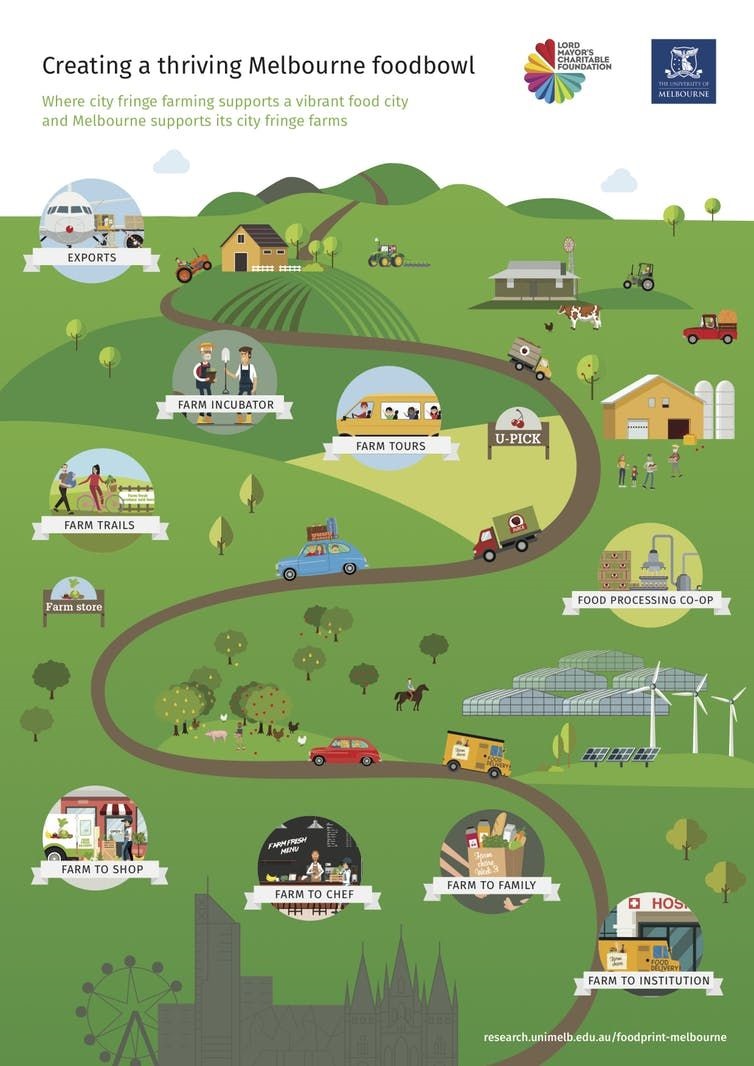

The Foodprint Melbourne project has just released an infographic that showcases the mutually beneficial relationships that can be developed between cities and the farmers on their fringes. These ideas were developed in workshops that brought Victorian stakeholders together from across sectors (farmers, industry, local government, state government and civil society) to explore how the viability of farming on Melbourne’s fringe could be strengthened.

The infographic shows how strong links between cities and local farmers can create a two-way exchange. Farmers can capture a higher share of the food retail dollar by selling direct to local consumers (through farmers markets or community-supported agriculture) or local businesses (such as cafes and restaurants). City residents benefit from access to fresh, local produce and from opportunities to participate in agri-tourism activities on nearby farms (such as pick your own produce and farm-gate bike trails).

Food from Melbourne’s foodbowl can also be sold directly to local families, shops and restaurants in the city, in addition to being transported interstate and overseas via city airports. A new provenance brand could be introduced so consumers and businesses can easily recognise food from the area and support local farmers.

Read more:

Urban sprawl is threatening Sydney's foodbowl

State and local governments could introduce food procurement standards so that government services, such as hospitals, prisons and “meals on wheels” programs, are encouraged to buy food from Victorian farmers. Government food procurement standards like these are already used in other countries, such as the United States and Canada.

Farmer incubators could be established to help new farmers access land and begin farming on the city fringe, mentored by experienced growers. Farmer-owned food-processing co-operatives could enable these growers to add value to their produce and take greater control of the food supply chain.

How to encourage city fringe farms to thrive

Cities around the world now recognise the importance of actively strengthening links with farmers on the city fringe. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation has released a “city region food system toolkit” that supports cities in building closer links with nearby farmers to improve farmer livelihoods, grow local economies and increase access to healthy, sustainable food.

A key step is to provide certainty about the future of farming areas close to cities by introducing laws that protect them for the long term. The city of Portland, Oregon, for instance, has created rural reserves that protect important farming areas for at least 50 years.

Measures to promote the viability of farming are equally important. In Ontario, the provincial government funds the Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation to promote farming, tourism and conservation in the agricultural area surrounding Toronto.

Read more:

Farming the suburbs – why can’t we grow food wherever we want?

The links between cities and the farmers on their fringes have weakened as modern food supply chains have developed, but there is renewed interest among consumers in reconnecting with where their food comes from.

To improve access to locally grown food and increase the resilience of food systems to climate change, we need to build mutually supportive relationships between cities and the growers on their fringes, so that farms thrive as our cities grow.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source: The Conversation Africa

The Conversation Africa is an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community. Its aim is to promote better understanding of current affairs and complex issues, and allow for a better quality of public discourse and conversation.

Go to: https://theconversation.com/africaAbout Rachel Carey, Jennifer Sheridan and Kirsten Larsen

Rachel Carey is a research fellow at the University of Melbourne.Jennifer Sheridan is a researcher in sustainable food systems at the University of Melbourne.

Kirsten Larsen is manager, food systems research and partnerships at the University of Melbourne.