Ecomimicry: the nature-inspired approach to design that could be the antidote to urban 'blandscapes'

All too often, attempting this balancing act ends up in “blandscaping”. Blandscaping is the practice of creating virtually uniform green spaces that are devoid of local character or distinctiveness. These bland landscapes arise when urban green spaces are designed with an entirely human focus: making them attractive to look at and easy to manage, but containing almost none of the valuable biodiversity that would otherwise have occupied the space.

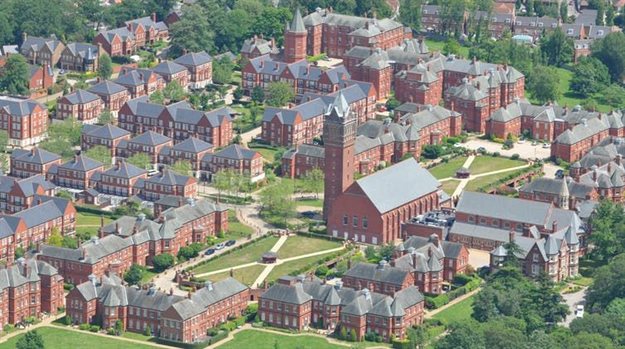

Rather than tailoring the built environment to the local landscape, blandscaping uses what might politely be called a “copy and paste” approach. Globally, similarly generic designs abound, often using the same materials – and the same species – across vast geographical areas.

Like a tidal wave of uniformity, this approach sweeps biodiversity aside. Just as the monocultures created by intensive single-crop farming have threatened a huge range of plant and animal species, blandscapes render formerly diverse ecosystems identical by removing the variety of habitat features – including different soil types, complex plant structures, and unique hydrological patterns – that allow nature to flourish.

The creatures that blandscaping benefits most are “urban generalists”: the kind of hardy animals that thrive almost anywhere, such as feral pigeons and house mice. These species prosper at the expense of others that require more specific habitats, including hedgehogs and rarer pollinators like the pantaloon bee.

The danger of blandscaping

Blandscapes are often celebrated for increasing biodiversity simply because they’ve replaced slabs of tarmac or concrete with something green. Typically focusing on evergreen hedges, exotic and complex flowering plants, lots of grassy areas to sit or walk, and a covering of woodchippings to suppress undesirable plant species, blandscapes can at first glance appear to provide a home for nature.

When the starting point is a square of sterile grey, adding any greenery might seem to be the best option. But the “any green is good” mantra misses opportunities to rewild our urban landscapes with the complex mosaics of nooks and crannies that help nature proliferate.

Far from being praised, blandscaping should be seen as the ecological equivalent of gentrification. Resident communities are being displaced under the guise of revitalising the area, and what remains is a habitat suitable only for the elite few rather than the many.

Throwing generic plants and soil into a landscape design is a form of ecological cleansing. Local species face little chance of survival when natural habitat diversity, which provides the range of resources needed to support all kinds of non-human communities, is removed.

The irony is that many of the post-industrial “wastelands” being blandscaped, such as the rapidly regenerating landscape of the Royal Docks, were much richer in the very biodiversity that we need to be protecting pre-development. In fact, some of the UK’s most biodiverse habitats can be found on unmanaged post-industrial sites like Canvey Wick, in Essex, where nature has been allowed to thrive by itself. Sites like these offer a far better blueprint for urban design than the cookie-cutter approaches typical of many city spaces.

When we confine ourselves to blandscapes, we miss out too. From birdsong to butterflies, proximity to nature carries a host of benefits. Why should we settle for unimaginative and exclusory urban environments, when the natural world has so much more to offer?

Ecomimicry: design inspired by nature

An emerging approach to urban design – ecomimicry – recognises the many lessons we can learn from the self-organising systems of the natural world. In the words of designer Van Day Truex, when it comes to design, Mother Nature is our best teacher.

An ecomimicry approach starts with reading the local landscape like a book. By getting to know how different parts of a regional ecosystem intertwine, urban designers can integrate the ecological functionality that already exists in the landscape – like an abundance of pollinators, natural flood defences and food – into what they build.

Examples include covering roofs in locally typical vegetation that can feed animals and humans, or building around, not over, coastal treasures like dunes and mangrove forests, and incorporating habitat features of these landscapes into the new surrounding landscaping to increase habitat connectivity, ecosystem service provision, and resilience.

With an awareness of nature’s importance gaining momentum, increasing numbers of entrepreneurs are developing nature-based designs with ecomimicry at their core. Welcoming biodiversity back into our urban areas can reconnect communities with nature, supporting equal access to the social, physical and psychological benefits nature provides us for free.

Our project, EU Horizon 2020 Connecting Nature, is working with cities worldwide to explore how to bring nature back into urban landscapes. We’re helping tease out the trade-off process between human and environmental needs that city planners face when trying to integrate nature. In doing so, we hope to introduce ecomimicry approaches to the mainstream and to restore cities to the biodiverse glory of the landscapes in which they lie.

If ecomimicry is to gain a foothold in our landscapes, three things are necessary: We must involve local ecologists who understand the unique complexities of the habitats being altered. We must ensure that the inherent value of all creatures is reflected in our approach to urban design. And we must embed this approach into policy, so it lasts for years to come.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Source: The Conversation Africa

The Conversation Africa is an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community. Its aim is to promote better understanding of current affairs and complex issues, and allow for a better quality of public discourse and conversation.

Go to: https://theconversation.com/africa