What do you think is the greatest ad campaign ever? Coca-Cola? Apple? Levi's? All great choices, but I'd argue that the most effective ad of all time was by De Beers. And part of its success was through the smart application of a simple psychological bias. A bias that you can still apply today.

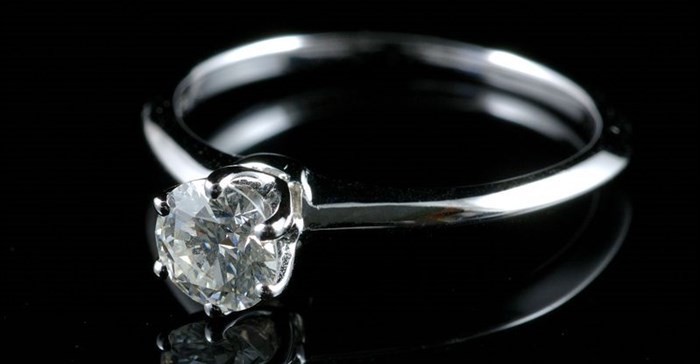

Back in the 1930s, diamonds weren’t the unthinking choice among Americans looking to buy engagement rings. People were as likely to buy emeralds or sapphires as diamonds. But De Beers made diamonds the natural choice for romantics by linking the durability of the stone with the eternal nature of true love. Frances Gerety’s 1947 tagline, “A diamond is forever”, helped forge this link brilliantly.

However, as ad man Rory Sutherland has said, it’s only the second-best line that De Beers coined: even better was the copy persuading consumers that the appropriate budget for a ring was a month’s salary.

This tactic is a simple application of the psychological principle called anchoring. If you mention a number, even an irrelevant one, people can’t help but be influenced by it. People recognised that a month's salary was slightly arbitrary, but they used it as the starting point when reflecting on how much to spend.

The evidence for anchoring dates back to 1974 and one of the most cited papers in the history of behavioural science: Judgement under Uncertainty by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

The scientific evidence

The paper included a novel experiment. The academics had participants spin a wheel of fortune and once it stopped they posed a question: “What proportion of African states are members of the United Nations?”

But, as in all psychology experiments, there was a twist: the wheel of fortune was rigged. It only stopped at two numbers: 10 or 65. This arbitrary number acted as an anchor in the experiment. When the wheel came to rest at 10, participants guessed that 25% of African states were members, whereas when it stopped at 65 they estimated 45%. The initial anchor significantly affected their judgement.

The academics believed that anchoring worked, not because the arbitrary number was deemed relevant, but because participants inadvertently used it as the starting point for their deliberations.

The students who saw the number 10 recognised that it was too low but they adjusted upwards from there. As the students were uncertain about the composition of UN member states they had a broad range of reasonable answers. As they moved upwards from the anchor they hit the lower edge of that range and decided upon that as their answer.

Those who had seen 65 on the wheel similarly knew it wasn’t accurate - but they began their calculations from a higher point and, adjusting from there, hit the upper edge of the range of reasonable answers.

A billion-dollar bias

But the story doesn’t end there. In the 1960's De Beers changed their advice in America. They said that actually you should spend two months’ salary on an engagement ring. Once again anchoring had the desired effect and people increased how much they were prepared to pay.

And then in the 1980s they launched in Japan, a country with no tradition of engagement rings at the time. This time they suggested that men should spend three months of salary to prove the depth of their love. Once again anchoring worked its magic.

The results have been exceptional. Not only did De Beers make diamonds the default choice for those looking to buy an engagement ring, but also people were prepared to spend lavishly. De Beers’ US diamond sales rose from $23m in 1939 to $2.1bn in 1979. Even accounting for inflation, that’s a nineteen-fold increase.

A simple application of a bias created one of, if not the most, successful campaigns in the world. Now all you need to do is think how can you introduce anchors into your communications and negotiations.