Subscribe & Follow

Jobs

- Digital Media Strategist Johannesburg

- Creative Director Cape Town

- Senior Media Sales Executive Sandton

- Digital Media Strategist Rosebank

- Integrated Client Service Lead Rosebank

- Head of Digital Johannesburg

- 2D Animator Johannesburg

- E-commerce Specialist Cape Town

- Media Planner Cape Town

- Customer Service (UK Market) - Work from Home Nationwide

SABC plan is antithesis of open journalism

At its heart, open journalism is about accepting, and embracing, a radically changing relationship between journalists and their audience.

On the news-gathering side, open journalism means taking on board that social media has given everyone the tools to operate as a journalist, sharing news and information with the world, and changing the way one works to take advantage of this, rather than see it as a threat.

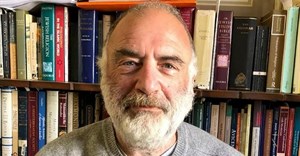

In the "10 ideas about open journalism" he shared on Twitter, Rusbridger said The Guardian would encourage participation by readers. It was no longer an "us to them" inert form of publishing. It involved encouraging debate, where the paper can follow its audience, rather than lead it. It can involve it in the process even before publication.

The paper would help form communities of interest around topics. It would link its stories to other material on the web, including aggregating and curating the work of others.

Transparent, and open to challenge

In this version, journalists are no longer the source of authority, expertise, and interest. Their reports may be the beginning, not the end point, of the journalistic process. And, importantly, open journalism is transparent and open to challenge - including correction, clarification and enhancement. This is part, he says, of the most profound changes in journalism since Johannes Gutenberg gave us movable type.

On the output side, it means avoiding as much as possible putting material behind a paywall, as The New York Times has done. As Rusbridger puts it, no journalist wants to erect a barrier between him and any potential audience. Besides, he thinks it is the right long-term financial strategy. Of course, because The Guardian is owned by a wealthy trust, it has the space to experiment. Few others are as fortunate.

Rusbridger's approach is about harnessing the strengths and intelligence of digital and social media. It is about seeing the wisdom of a crowd, as opposed to a single voice of sometimes fake authority.

He illustrates this by saying The Guardian's theatre reviewer is as important as ever, but now the paper can find ways to make use of the views of the other 500 people in the theatre. It takes in bloggers, tweeters, and those who just like to comment.

Out of step

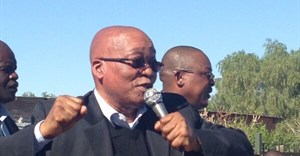

I raise this because it illustrates how out of step with current thinking is the call by South African Broadcasting Corporation chief operations officer Hlaudi Motsoeneng for journalists to be licensed and more tightly regulated and controlled. It is the very antithesis of where the best and most progressive of global journalism are headed. It is opting for a Chinese or Zimbabwean model over the openness and transparency we embraced in our constitution.

The last people to call for the licensing of journalists and statutory regulation of journalists in South Africa were the apartheid ministers who routinely said that our media were too negative. Motsoeneng is now the spokesman for this anachronism, but it is one version of a view one is increasingly hearing from elements among the African National Congress leadership. The shock is that it should come from someone in a position of media leadership, who is wishing this on his own staff.

A primary reason we opt for democracy and openness, with all its irritations, is that it is the best way to allow a society to self-correct when it makes mistakes. One of South Africa's great strengths is that we can fix the mistakes made in the first 20 years of democracy.

That can happen only with a free and open media in which these issues are openly debated and options explored. In particular, the private media - for all their faults - are among those few of our institutions of accountability not controlled by those who hold the power of the state. The press is an independent institution that helps protect the independence of all the other institutions.