Investing R500 monthly is a fairly easy exercise, but this becomes an infinitely more difficult one when investing a large lump sum e.g. R3,000,000.

The problem can be further exacerbated if the investor and his adviser perceive the market to be somewhat expensive. Many market participants have proposed different strategies for dealing with this stressful decision. One strategy is to phase-in the lump sum investment over a specified period of time. The purpose of this article is to explore the merit of this strategy.

The most obvious first question is, does phasing-in work? Many people are quick to respond that it does not, and simply leave it at that. This view is rather myopic in my opinion. I wager that most so quick to dismiss this strategy have never provided advice nor invested on behalf of a client. If one could quantify anxiety and stress and then add this onto the expected returns on the investment, then one may want to ask the question, would phasing-in still be so easily written off. While we can only speculate, it remains an interesting question and one worth asking yourself.

This article will investigate if there are indeed periods when phasing-in works. It will look at different phasing-in periods to determine if certain periods are more favourable to use than others. In addition it attempts to identify market signals that may help in deciding whether or not to use phasing-in as an investment strategy.

An important start is to clarify the methodology and parameters used. The return period was 15 years using monthly rolling total returns from 1 January 2000 until 30 April 2015. These were compounded to compute the total return as well as the volatility of the different strategies. Three months, six months, 12 months, 18 months and 20 months phasing-in periods were then used. The outcome of this strategy was then directly compared to investing in the same basket of equity funds without phasing-in.

Now that we understand the methodology used, we can turn our attention to phasing-in. The most important principle to be aware of when phasing-in, is that you are de-risking your investment. In essence you are taking on less risk by combining a mixed exposure of equity and cash for a certain period of time thereby limiting capital losses on your initial investment in times where you may perceive the market to be too expensive.

However, this could also result in lower returns should the market continue to rise. One can argue that if the end goal is to be invested in equity (or a risky asset), one should not really concern yourself with risk. While I agree with this, it can be argued that there is a very big difference in one's ability and willingness to tolerate volatility over very long periods of time, and one's willingness to tolerate a significant drawdown in a very short period of time, especially when it is close to one's initial investment.

The impact of a significant drawdown becomes far less of an issue the longer one has been invested. The opposite of course is also true. A significant drawdown close to one's initial investment date is compounded the longer one's investment horizon is. This study will, however, attempt to show that as a portfolio is 'de-risked', lower returns need not necessarily be the outcome.

When comparing phasing-in over the various periods relative to the performance of equity funds (blue bar in the chart below) the following question may be asked: So does phasing-in work?

Well, the answer is, it depends. As the blue bar in the graph above shows, almost 75% of the time it does not work. However, this does not mean it never works. In fact, over a 15 year period it worked four out of the 15 years and it worked well. Would it therefore not make sense to explore those instances when it did work as opposed to simply dismissing it altogether?

The chart also shows that as the phasing-in period decreases, the probability of the phasing-in strategy delivering performances equal to, or better than directly investing in equity funds, increases slightly. Intuitively this makes sense, as one is invested in lower yielding cash instruments as opposed to equity for a shorter period of time.

So would it be better to select a shorter phasing-in period? Not necessarily, as choosing the shortest possible period most closely reflects the returns of the pure equity fund and is the most risky strategy. As the rationale for phasing-in is to de-risk the portfolio - choosing this strategy defeats the objective. In fact, this study shows one will under-perform the pure equity fund almost 65% of the time, but with a lot less possible upside.

What other alternatives are there to de-risk your initial investment? Two other strategies commonly used are where investors 'park' their investments in either a balanced or flexible fund as opposed to cash. The idea is to move these funds into a pure equity fund once they perceive the market or equities to be less expensive.

According to this study using a balanced fund increases the odds firmly in favour of phasing-in. The results using a flexible fund were a little less favourable. What do you think the reason is?

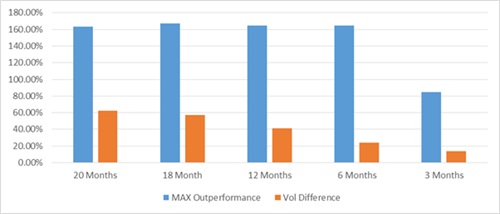

When comparing various terms of phasing-in and volatility relative to the basket of equity funds some interesting observations can be made.

Not only did the longer phasing-in periods provide superior out-performance, these longer periods also registered the most significant differences in volatility, so potentially you can register significant out-performance, but with a lot less volatility, as opposed to directly investing in equity. Therefore using a short phasing-in period seems to not make sense.

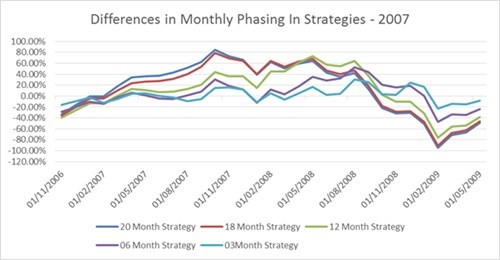

In order to identify if there are any market signals that indicate when phasing-in may work (and if there are some notable lessons we can take from this) we need to have a look at when phasing-in actually did work. Phasing-in worked well during very specific periods in the last fifteen years, most notably the periods during 2001/2002, just after September 2001, and then again during 2007/2008 which is hardly surprising. See the graph below which indicates the differences in returns, between the phasing-in strategy and directly investing in the same basket of equity funds. Positive differences are indicative of when phasing-in worked.

Note that the differences in the early 2000s are more prominent due to compounding and being further away from the present day. As we move closer to the present, these differences become less prominent.

At closer inspection, it becomes further apparent that the longer the phasing-in period, the better the pay-off. In the 2001/2002 period, the 20 month period, 18 month period and 12 month period performed well, with the first two delivering higher out-performance, but the 12 month period delivering longer out-performances. However in the 2007/2008 period the 20 month and 18 month periods would have seemed to be the most obvious choices.

It is also very apparent that there are extended periods of time when phasing-in did not work and that the potential under-performance is more significant than the out-performance.

Following the identification of those periods when phasing-in did and did not work let's try and see if there are certain signals when it is favourable or not favourable to use this strategy. Let's first look at whether it is possible to identify a reliable method in this decision. Here a couple of metrics were considered with the first obvious choice being valuations e.g. the price-earnings (PE) ratio of the JSE.

One standard deviation was added to the rolling long-term average PE ratio. Comparing this to the PE ratio of that specific time gives us some sort of idea of how expensive the JSE was. If it is above the long-term average plus one standard deviation, it is deemed expensive and if it is below the long-run average, less one standard deviation, it is deemed to be cheap. This research delivered no discernible relationship and no clear way of determining when one could start phasing-in by looking at the PE ratios in isolation. What it did indicate is that when the PE ratio is extremely low, phasing-in will most definitely not work and should not be attempted.

A metric that did however work relatively well was the interest rate. The assumption is that when interest rates rise, markets respond negatively. There is a decline in valuations, as discount rates increase, and future cash-flows are discounted at a higher rate. This relationship can be seen clearly in the graph below.

During 2001/2002 we saw four interest rate increases of 100 basis points each, and during the 2007/2008 period we saw ten interest rate increases of 50 basis points each. From this we may deduce that when there are significant interest rate movements, phasing-in starts working almost immediately.

Secondly, the window period when phasing-in does work, becomes narrower. When interest rate increases are less severe however, there is a slight lag in which phasing-in starts to work, but the window period of when it works is longer. Thirdly, there needs to be a couple of consecutive interest rate increases for phasing-in to be successful. What is especially worthwhile to point out is that in both instances, phasing-in works even after the rate increases start.

The opposite also holds true and indicates quite clearly when phasing does not work. Therefore phasing-in should not be used during times of easing monetary policy, when interest rates are declining.

The relationship between interest rates and phasing-in can also be explained by theory. As interest rates rise, you want to be exposed to shorter duration instruments. The longer the duration, the more sensitive your investment will be to a changing interest rate environment. Typically the longer the time-horizon for an investment the higher its duration will be, as more of the return will be discounted at different, uncertain future interest rates.

As your investment reaches its maturity, more of the value has been realised and less future benefits will need to be discounted at less uncertain rates. Therefore, during a phasing-in strategy you increase your exposure to a very short duration instrument, cash, that actually gains from rising interest rates, while at the same time putting you in a situation where you purchase stocks at lower valuations. Phasing-in can therefore potentially lead to handsome out-performance while at the same time reducing your risk.

Another possible benefit of phasing-in, is the option value of cash. Having options in times of high market volatility is beneficial, and also one of the reasons why call and put options become more expensive during these times. Cash gives you that option, but without the costs involved in purchasing put or call options.

To conclude, phasing-in as a strategy does not work in most instances. However there are times when it does. Should you decide to phase-in as a deliberate risk aversion strategy, it is better to select longer time periods to phase-in as opposed to a three-month period or a six-month period and in periods of significant or frequent interest rate hikes.

The advantages of using valuations to decide when to phase-in is less obvious. It does however indicate when it does not work. This is when valuations are extremely low and interest rates are in a declining or a very stable interest rate environment. The size and frequency of the interest rate movements should always be taken into account, to determine your window of opportunity.

This may beg the question: In what type of environment are we currently? This is difficult to answer directly, but looking at the fixed income market it does seem as if the markets are pricing in quite a bit of inflation and subsequent rate hikes. On the other hand the global economy is still very much leveraged so quick, successive and substantial rate hikes will be difficult to stomach. Ultimately it is difficult to call the market or time the exact point at which interest rates will start to rise.

From this study it would seem that phasing-in does offer opportunities even after this has started. Therefore trying to avoid risk in a rising interest rate environment might well be a very real and viable option. There is the potential benefit of significantly outperforming an immediate lump-sum investment into an equity fund, at lower volatility, with the added advantage of less emotional stress.

If you expect that we might be entering a rising interest rate environment that is significant and/or the frequency of the hikes will be smaller but often, phasing-in might well be a viable strategy for you.